3.1 KEY CONCEPT: Readability

All documents have a purpose—to persuade, to inform, to instruct, to entertain—but the first and foremost purpose of any document is to be read. Choosing effective document design enhances the readability of your document so that the target audience is more likely to get the message you want them to receive, and your document is more likely to achieve your intended purpose. Documents are also designed with usability in mind. That is, effectively designed documents are created from a user-experience perspective: if a reader can easily learn to use the document and find content, then you will have achieved a usable design.

Keep in mind that people do not read technical writing for pleasure; they read it because they have to; it’s part of their job. And since “time is money,” the longer it takes to read the document, the higher the “cost.” Your job as the document designer is to make their reading process as easy, clear, useful and efficient as possible by using all the tools at your disposal. For example, choose document design elements, like a 12-point, sans serif font or headings and subheadings, that make your document “user friendly” for your target audience.

Designing a document is like designing anything else: you must define your purpose (the goals and objectives you hope your document achieves), as well as the constraints — such as word count and format — that you must abide by, understand your audience (who will read this document and why), and choose design features that will best achieve your purpose and best suit the target audience. In essence, you must understand the Rhetorical Situation (see Chapter 1.3) in which you find yourself: Who is communicating with whom about what and why? What kind of document design and formatting can help you most effectively convey the desired message to that audience? You want to use the most effective rhetorical strategies at your disposal; document design is one of those strategies.

Genres and Conventions

It’s not only the content and rhetorical strategies that have differing conventions; documents also differ in how they are designed and formatted. All genres of writing adhere to certain conventions in terms of content, the style of language used to express that content, and how the content is presented visually. If you look at an online news article (or an article in an actual newspaper), you will often notice consistent formatting features.

As you learned in previous writing classes, readers in different contexts expect different textual features, depending on the type of document they are reading and their purpose. A reader of an online editorial can expect strongly worded arguments that may rely on inflammatory emotional language but not be backed up with much empirical evidence; we do not expect an online editorial to cite reliable sources in a scholarly format. In contrast, an academic reader expects the opposite: neutral, unemotional language, and plenty of empirical evidence to logically and validly support claims, with sources cited and documented in an appropriately academic bibliographical formats. In technical contexts, readers expect

- content that is fact-based and specialized

- language that is concise, clear, and precise

- information that is supported with graphs, charts, and other visual aids

- formatting that is functional

- Large headlines, often using rhyme, alliteration, exaggeration or some other rhetorical device to grab attention

- Very short paragraphs (generally 1-3 sentences long)

- Pictures related to the article

- A cut-out box with a particularly attention-grabbing quotation from the article in larger, bolder print (to get readers interested in the article)

- Advertisements on the side

See below for a discussion of formatting conventions for technical documents.

It is important for writers to understand the conventions of the genre in which they are writing. Conventions are the “rules” or expectations that readers/viewers have for that particular genre or medium. If you do not follow the target readers’ expectations, you run the risk of confusing them—or worse, damaging your credibility—and therefore not effectively conveying your message and fulfilling your purpose. Think of document design as “visual rhetoric.” Make document design choices that best conform to the expectations of the genre and audience, and that most effectively convey the message you want to send.

Style Guides and Templates

In many writing contexts, style guides and templates will be available. Style guides dictate the general rules and guidelines that should be followed; templates offer specific content and formatting requirements for specific kinds of documents. Academic publishers make style guides available to prospective authors so that they know how to properly write and format documents they submit for publication. Newspapers, academic journals, organizations, and businesses often have their own “in-house” style that must be followed by all writers within that organization. A company may have specific templates, for example, a memo template, that all employees must follow, in order to ensure consistency of messaging.

You likely had a style guide to help you format your written assignments for your introductory technology classes, and in science classes, you likely had a template to help you organize lab reports.

EXERCISE 3.1.1 List some conventions of academic formatting

Examine the formatting in Figure 3.1.1 below and list some of the characteristics that adhere to academic writing format requirements that you are familiar with. It does not matter if you cannot read the text; simply examine the formatting.

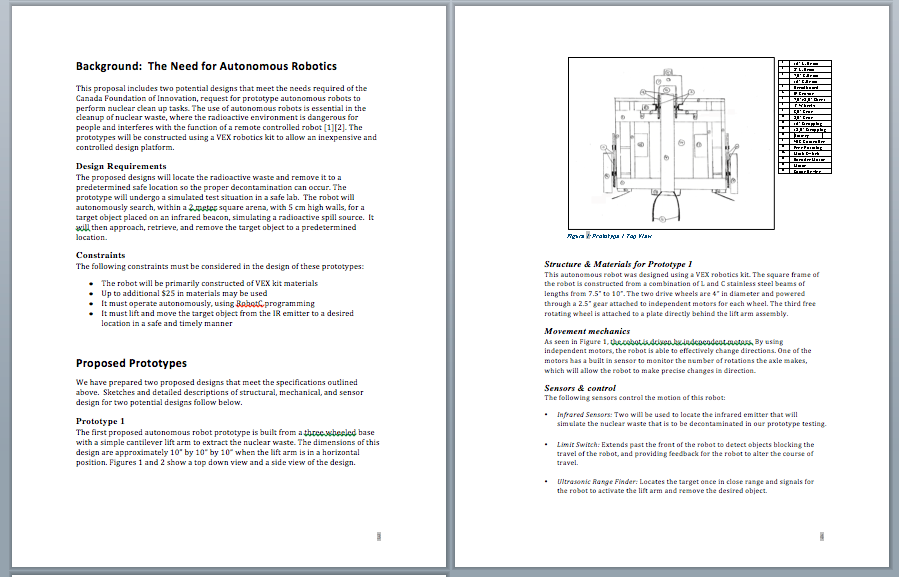

Now examine the document in Figure 3.1.2. What differences do you notice? List some of the features that differ from the academic writing sample above. Consider why typical readers of technical writing would find these features desirable. Which document would you rather read?

Technical writing makes use of several typical design features to organize information efficiently and enhance readability. These include headings, lists, figures, and tables, as well as strategic use of passive space around all of these features and text. Each company, publisher, or organization may have its own style guide to which all writers within that organization, or those wishing to contribute written material, must adhere. In BTC440, SES391, and TEC400, we use the APA Style Guide. To get you started on applying a style guide to your writing, all work written for BTC440, SES391, and TEC400 should adhere to the basic guidelines briefly described below.

Basic Style Guide for BTC440, SES391, and TEC400 Written Assignments

Most workplace documents are created using Microsoft Office products (Word, Excel, and PowerPoint) or using Google Drive tools such as Google Docs and Google Slides. This is generally industry standard, so it is crucial that you learn how to use these programs effectively to create sophisticated workplace documents.

The general specifications of technical writing documents that you can format in MS Word are as follows:

| Margins | 1 inch on all sides; justify left margin only; leave the right margin ragged for easier reading If you are binding your report, leave a 2-inch left margin |

| Body Text Font | Use either a serif or sans serif font depending on the context. Serif fonts include typefaces like Times New Roman and Cambria. Sans serif fonts include typefaces like Arial, Calibri, Verdana, etc.** |

| Heading Font | The MS Word Styles tool formats headings using a sans serif font. |

| Font Size | 11-12 point font (12 is preferred) for body text 12-20 point sans serif font for headings and subheadings. |

| Paragraphs |

Single spaced; no indentation; extra space between paragraphs; no more than 10 lines in length, with no more than 15-20 words per line. Letters and memos are always single-spaced; reports may be single, 1.5 spaced. Drafts are often double-spaced to make room for comments. |

For specific document elements such as title page, letter of transmittal, and table of contents, see SELS’s A Guide to Writing Formal Technical Reports: Content, Style, and Format (Potter, 2021).

The rest of this chapter offers specific and detailed information on how and why technical writers use the following document design features:

- Headings: Headings and subheadings provide a clearly visible organization and structure that allows readers to read selectively and preview information. We include here several guidelines for font style, size and color to help you design headings effectively.

- Lists: Lists provide a way to concisely and efficiently convey information and emphasize ideas. There are several kinds of lists, each used for specific purposes.

- Figures and Tables: Visual representations of data and concepts serve to illustrate, clarify, and support ideas, while offering a reader a break from reading text-heavy pages.

- Passive Space: Leaving blank spaces strategically on the page (around lists, figures, and headings, and between paragraphs) helps the reader to absorb the information in the “active” space more effectively, and helps writers create a visually appealing look.

** NOTE: While a common misconception holds that sans serif fonts make electronic documents easier to read, font preferences vary, and persons with specific disabilities require either the serif or sans serif font to improve their ability to read documents. For example, the CNIB Clear Print guidelines recommend use of the sans serif font when creating documents for persons with visual impairments (n.d.). Assistive technologies can easily adapt documents for persons with disabilities by customizing the font (APA, 2020; WebAIM, 2020). When possible, check with the intended audience to see which is preferred. As a default, however, use your organization’s style guide to create readable documents. For example, Seneca College’s A Guide for Creating Accessible Documents 2012 states: “San [sic] serif fonts, such as, Frutiger, Arial, and Verdana are preferable” (2012, p. 10). For more information on choosing font styles, see CNIB (n.d.), American Psychological Association (2020), and WebAIM (2020).

References

American Psychological Association (APA). (2020, June). Accessible typography. APA Style. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/accessibility/typography

CNIB. (n.d.) Clear print accessibility guidelines. PDF. https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:24b42b46-a3b4-4b67-93c6-3e58695e201b

Last, S. (2019). Technical writing essentials. BCcampus. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/

Seneca College. (2012). A guide for creating accessible documents 2012. PDF. https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:47f00529-983f-4446-b1a5-bae9eca8c2a8

Potter, R. L. (n.d., 2017, 2021). A guide to writing formal technical reports: Content, style, format.

Original document by University of Victoria (n.d.). Engineering work term report guide: A guide to content, style and format requirements for University of Victoria engineering students writing co-op work term reports. (Updated by Suzan Last, October, 2017 and adapted by Robin L. Potter (2021). OER.

WebAIM. (2020, October 27). Typefaces and fonts. https://webaim.org/techniques/fonts/