8.2 Proposals

The Life Cycle of a Project Idea

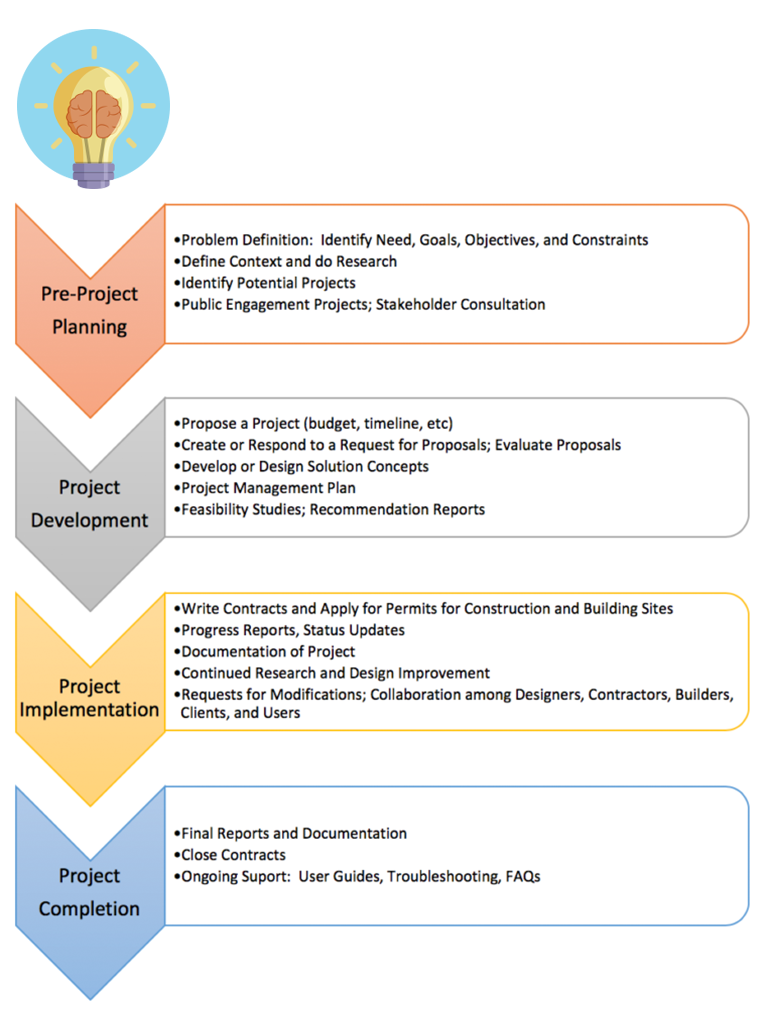

A great idea does not usually go straight from proposal to implementation. You may think it would be a great idea to change the design of the office space in your department, but before anyone gives you the go ahead for such an expensive and time-consuming project, they will need to know that you have done research to ensure the idea is cost effective and will actually be workable for your employees. Figure 8.2.1 breaks down the various stages a project might go through, and identifies some of the typical communication tasks that might be required at each stage.

Most ideas start out as a proposal to determine if the idea is really feasible, or to find out which of several options will be most advantageous. So before you propose the new office design, you propose to study whether or not it is a feasible idea. Before you recommend any specific office concept, you should propose to study three different concepts to find out which is the best one for your department. Your proposal assumes the idea is worth looking into, convinces the reader that it is worth spending the time and resources to look into, and gives detailed information on how you propose to do the “finding out.”

Knowledge Check

Once a project is in the implementation phase, the people who are responsible for the project will likely want regular status updates and/or progress reports to make sure that the project is proceeding on time and on budget, or to get a clear, rational explanation for why it is not. To learn more about Progress Reports, go to 8.4 Progress Reports.

Proposals

(How to write a Business Proposal in 10 Easy Steps, n.d.)

Proposals are some of the most common types of reports you will likely find yourself writing in the workplace. Variants of proposals include business plans and marketing plans. Proposals are persuasive documents intended to initiate a project often in response to a challenge and get the reader to authorize a course of action proposed in the document. Proposals may be informal, short document, addressing a need or challenge in your workplace, or the proposal may be a more formal and lengthy document that responds to a call for proposals for a complex project.

A proposal, in the technical sense, is a document that tries to persuade the reader to implement a proposed plan or approve a proposed project. Most companies and organizations rely on effective proposal writing to ensure successful continuation of their business and to get new contracts. With an effective proposal, the writer convinces the reader that the proposed plan or project is worth doing (worth the time, energy, and expense necessary to implement), that the author is the best candidate for implementing the idea, that the proposed plan is realistic and feasible, and that the proposed course of action will result in intangible benefits.

Lengthy proposals are often written in response to a Request For Proposals (RFP) issued by a government agency, organization, or company. The requesting body receives multiple proposals responding to their request, reviews the submitted proposals, and chooses the best one(s) to go forward. Your proposal must persuade the reader that your idea is the one most worth pursuing.

Proposals may serve several purposes, which include seeking to obtain authorization to

- perform a task (such as a feasibility study, a research project, etc.),

- provide a product, or

- provide a service.

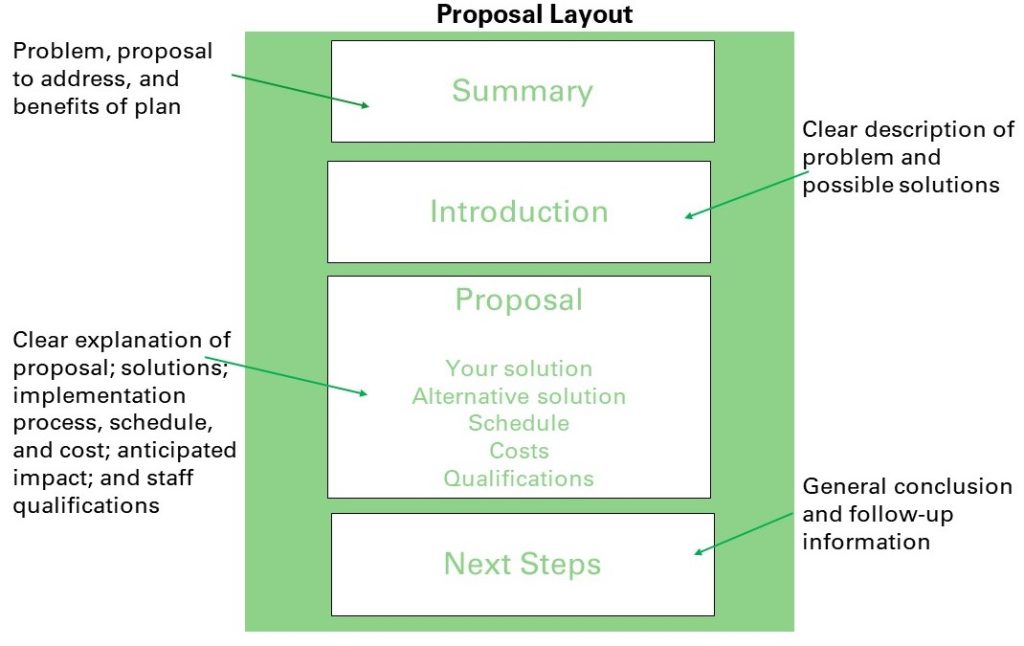

Figure 8.2.4 presents the general outline for proposals irrespective of purpose.

Four Kinds of Proposals

(Types of Business Proposals, n.d.)

- Solicited Proposals: An organization identifies a situation or problem that it wants to improve or solve and issues an RFP (Request for Proposals) asking for proposals on how to address it. The requesting organization will vet proposals and choose the most convincing one, often using a detailed scoring rubric or weighted objectives chart to determine which proposal best responds to the request.

- Unsolicited Proposals: A writer perceives a problem or an opportunity and takes the initiative to propose a way to solve the problem or take advantage of the opportunity (without being requested to do so). This can often be the most difficult kind of proposal to get approved and so should include a persuasive rationale for the proposed course of action.

- Internal Proposals: These are written for someone within the same organization as the writers. Since both the writer and reader share the same workplace context, these proposals are generally shorter than external proposals and usually address some way to improve a work-related situation (productivity, efficiency, profit, etc.). As internal documents, they are often sent as memo reports, or introduced with a memo transmittal document if the proposal is lengthy.

- External Proposals: These are sent outside of the writer’s organization to a separate entity (usually to solicit business). Since these are external documents, they are usually sent as a formal report (if long) and introduced by a letter of transmittal. External proposals are usually sent in response to a Request for Proposals, but not always.

Knowledge Check

EXERCISE 8.2.1 Task Analysis

Identify the kinds of proposals you would be likely to write within the business you will be joining upon graduation. Place them within the grid below. Given the kinds of proposals you would write, what forms would you use (memo report, letter report, or formal report)?

| Solicited | Unsolicited | |

| Internal

|

||

| External |

Key Features of Proposals

A proposal designed to affect readers’ opinions about public policies differs from one that proposes to conduct market research for a particular company. Accordingly, the following analysis of key features is presented as a series of considerations as opposed to a comprehensive blueprint. Always adapt your proposal to the context, audience, and purpose.

Tighten the Focus

Proposal writers bring focus to their proposals by highlighting the urgency of the problem and by providing the evidence readers need to believe the proposed solution can work. Having a solid understanding of the opportunity and challenge that forms the basis of the proposal will enable you to address the situation in a manner that is convincing and realistic, so always analyze the circumstances underlying the situation as you plan your work.

Use Concrete Development

It’s true that some proposals are won on appeals to emotion. But ultimately, an argument needs to be based on reason. You need to conduct research to find the facts, opinions, and research that support your proposed course of action or offer. Investigate what others have done in similar situations and which approaches have worked or have not been so successful. With this knowledge, you can then create your own innovative approach.

Reading sample proposals can help you find and adopt an appropriate voice and persona. By reading samples, you can learn how others have prioritized particular criteria.

Define the Problem(s)

Obvious problems can be defined briefly; whereas, more subtle problems may need considerable development. Thus, this part of your proposal may be as short as a sentence or many pages long–depending on the amount of detail you are required to provide. However, since proposals focus on the solution, the trend is to keep the problem overview as concise as possible, while showing that you understand the situation at hand.

When they read the introduction to your proposals, readers are likely to ask these questions:

- Does this proposal address our needs?

- Who benefits from the proposal?

- Will the project have significant impact?

- Do the proponents have a sufficient understanding of the issue?

- Who is submitting the proposal?

- What is their interest in solving the problem?

In order to answer these questions, provide specifics including statistics, quotes from authorities, results from past research, interviews, and questionnaires. Notice how the following excerpt stuns readers in its subheading with statistics. These statistics provide the background information that readers may need to understand a proposal written on the subject:

The new report, based on a survey of employed Canadians 45+ and retirees that was conducted by Pollara Strategic Insights, finds that the overwhelming majority of working Canadians have started to save for their retirement. But, despite this positive finding, only 20 per cent feel very confident about how to manage and grow their money once they enter their retirement years and just half (53 per cent) have given it any thought at all. (Mackenzie Investment, 2021)

Define Your Method(s)

How will you gather information (secondary research or primary research)? In the humanities, writers do not explicitly mention their methods; whereas, in business, sciences, and social sciences writers often explicitly mention their methods. For example, if you are proposing to conduct research, your readers will want information regarding how you propose to conduct the research. Will your research involve Internet and library research? Will you interview authorities or conduct a survey? If you are proposing a service, readers will want to ensure you can actually provide the service. Offer testimonials or other evidence of your successes, in this case.

Present Your Solution(s)

Successful proposals are not vague about proposed solutions. Instead, they tend to outline step-by-step activities and objectives, perhaps even associating particular activities and objectives with dollar figures–if money is sought to conduct the proposal.

Critical readers are likely to view proposals skeptically, preferring inaction (which doesn’t cost anything) to action (which may involve risk). As they review the solutions you propose, they may ask the following three questions:

- Is the solution feasible and realistic?

- How much time will it take to complete the proposal?

- Will other factors resolve the problem over time? In other words, is the problem urgent?

- What will it cost to implement, and what will the financial gains be over time?

Appeal to Character/Persona

People often imply or explicitly make “appeals to character.” In other words, they attempt to suggest they have credibility, that they are good people with the best interests of their readers in mind.

The persona you project as a writer plays a fundamental role in the overall success of your proposal. Your opening sentences generally establish the tone of your text and present to the reader a sense of your persona, both of which play a tremendous role in the overall persuasiveness of your argument. By evaluating how you define the problem, consider counterarguments, or marshal support for your claims, your readers will make inferences about your character.

To establish credibility, ensure that your approach is balanced, unbiased, and fair. Account for potential arguments against your proposed approach. Show why your approach is the feasible and cost-effective without fudging the details. Honesty will go a long way to establishing the value of your proposal.

Use Confident and Logical Language

Proposals are fundamentally persuasive documents, so paying attention to the rhetorical situation—position of the reader (upward, lateral, downward or outward communication), the purpose of the proposal, the form, and the tone—is paramount. Your task is to use a confident tone to convince the reader that your project is accurate, feasible, realistic, and beneficial to the reader. While employing persuasive writing strategies, it is important to avoid common logical fallacies. To review the principles of persuasive writing, please go to: Writing to Persuade

Generally, the following principles will help you develop a style that is suited for proposals:

- Clearly define your purpose and audience before you begin to write.

- Be sure you have done the research so you know what you are talking about.

- Remain positive and constructive; don’t blame people or dwell on the negative; rather, focus on the path forward.

- Be solution-oriented; you are seeking to improve a situation.

- Make your introduction very logical, objective, and empirical; don’t start off sounding like an advertisement or sounding biased.

- Use primarily logical and ethical appeals; use emotional appeals sparingly.

- As always, adhere to the 7 Cs by making sure that your writing is

- Clear and Coherent: Don’t confuse your reader with unclear ideas or an illogical structure.

- Concise and Courteous: Don’t annoy your reader with clutter, unnecessary padding, inappropriate tone, or hard-to-read formatting.

- Concrete and Complete: Avoid vague generalities; give specifics. Don’t leave out information necessary for decision-making.

- Correct: Don’t undermine your professional credibility by neglecting grammar and spelling or by including inaccurate information.

Knowledge Check

Additional Considerations

All proposals must be convincing, logical, and credible, and to do this, they must consider audience, purpose and tone. They are persuasive documents, so all components must be carefully considered as you integrate them into the document. You should also do the following:

- Describe your qualifications to take on and/or lead this project; persuade the reader that you have the required skills, experience, and expertise to complete this job.

- Include graphics to illustrate your ideas, present data, and enhance your pitch.

- Include secondary research to support your claims and to enhance your credibility and the strength of your proposal.

- Choose the format according to the context; is this a memo report to an internal audience or a formal report to an external audience? Does it require a letter of transmittal?

Proposal Organization

Each proposal will be unique in that it must address a particular audience, in a particular context, for a specific purpose. See the sample proposal below for an example. The following Table 8.2.1 offers a fairly standard organization for many types of proposals:

Table 8.2.1 Typical Business Proposal Format (Moxley, 2009, 2012, 2018)

| Executive Summary | Like an abstract in a report, this is a one- or two-paragraph summary of the product or service and how it meets the requirements and exceeds expectations. |

| Introduction |

Clearly and fully defines the problem or opportunity addressed by the proposal, and briefly presents the solution idea; |

| Background/Market Analysis |

Convinces the reader that there is a clear need, and a clear benefit to the proposed idea.

What currently exists in the marketplace, including competing products or services, and how does your solution compare? |

| Proposal | The idea. Who, what, where, when, why, and how. Make it clear and concise. Don’t waste words, and don’t exaggerate. Use clear, well-supported reasoning to demonstrate your product or service. |

| Benefits | How will the potential buyer benefit from the product or service? Be clear, concise, specific, and provide a comprehensive list of immediate, short, and long-term benefits to the company. |

| Timeline | A clear presentation, often with visual aids, of the process, from start to finish, with specific, dated benchmarks noted. |

| Marketing Plan | Delivery is often the greatest challenge—how will you get the word out, if this is a requirement of the project? |

| Finance/Budget | What are the initial costs, when can revenue be anticipated, when will there be a return on investment (if applicable)? Again, the proposal may involve a one-time fixed cost, but if the product or service is to be delivered more than once, an extended financial plan noting costs across time is required. |

| Conclusion | Like a speech or essay, restate your main points clearly, emphasizing the benefits of your plan. Request for authorization to proceed. Include a time limit of offer to protect your costs. |

| References |

Include complete references for citations and summarized content. |

Knowledge Check

Sample Proposal

Here below in Figure 8.2.2 is a sample research proposal.

Why Project Proposals Might be Rejected

A proposal or recommendation needs research to convince the reader that the idea is worth pursuing or implementing. A project proposal could be rejected for any of the following reasons related to insufficient research:

Unclear Problem: The research problem is not clearly defined so the research plan has no clear focus (your ideas are too vague and not well thought out)

Unnecessary Project: This issue is already well-known or the problem has already been solved (or is in the process of being solved). For example, proposing that the school cafeteria should replace plastic cutlery with compostable cutlery, when it has already done so, would result in a rejected proposal.

Impractical Scope: Access to information, resources, and equipment needed to complete your proposed study may not be available; adequate conclusions cannot be reached in the designated time frame and with resources available. For example, if you propose to do a study that will take two years, but your project is due in two months, the proposal will be rejected.

Be sure to submit your proposal to a thorough review before sending it to the procurer.

References

Ewald, T. (2017). Writing in the technical fields: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Greeg, U. (n.d.). Types of business proposals [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTSah0Sf_fU

[Lightbulb image]. https://www.iconfinder.com/icons/667355/aha_brilliance_idea_think_thought_icon. Free for commercial use.

Mackenzi Investment. (2021, September 23).Mackenzie Investments Retirement Study: Canadians are saving for retirement, but majority lack confidence on how to manage their nest egg. https://www.mackenzieinvestments.com/en/media-centre/press-releases/_2021/2021-september-23-mackenzie-investments-retirement-study-canadians-are-saving-retirement

McMurrey, D. (1997-2017). Examples, cases, and models. Online technical writing. https://mcmassociates.io/textbook/models.html

Moxley, J. (2009/2012/2018). Proposals. In Professional and technical communication (2019). OER. Suzie Baker, Adapter. https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/54645-professional-and-technical-writing/7/view

[Proposal image]. [Online]. Available: https://pixabay.com/en/couple-love-marriage-proposal-47192/. Pixabay License.

Williams, V. (2020). Business proposals. Fundamentals of business communication. OER. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/businesswritingessentials/chapter/chapter-13-business-proposals/

SMB Guide. (n.d.). How to write a business proposal [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p6kTK6HfS4Y

Image descriptions

Figure 7.2.1 image description:

Once there is an idea, a project goes through a design process made up of four stages.

Pre-project planning.

- Problem Definition – identifying needs, goals, objectives, and constraints.

- Define context and do research.

- Identify potential projects.

- Public engagement projects; Stakeholder consultation.

Project Development.

- Propose a project (budget, timeline, etc.).

- Create or respond to a request for proposals, evaluate proposals.

- Develop or design solution concepts.

- Project management plan.

- Feasibility Studies, Recommendation Reports).

Project Implementation.

- Write contracts and apply for permits for construction and building sites.

- Progress reports, status updates.

- Documentation of project.

- Continued research and design improvements.

Project completion.

- Final reports and documentation.

- Close contracts.

- Ongoing Support: User Guides, Troubleshooting, FAQs.