Unit 18: Emailing

Learning Objectives

After studying this unit, you will be able to

After studying this unit, you will be able to

-

-

- identify characteristics of effective professional emails

- understand how to compose effective professional emails

-

Introduction

The video introduced you to electronic mail, widely known as “e-mail” or just “email,”. As the video noted, by volume, emails are the most popular written communication channel in the history of human civilization. With emails being so cheap and easy to send on desktop and laptop computers, as well as on mobile phones and tablets, a staggering 280 billion emails are sent globally per day (Radicati, 2017)—that’s over a hundred trillion per year. Most are for business purposes because email is such a flexible channel ideal for anything from short, routine information shares, requests, and responses, to important formal messages delivering the content that letters and memos used to handle. Its ability to send a message to one person or as many people as you have addresses for, integrate with calendars for scheduling meetings and events, send document attachments, and send automatic replies makes it the most versatile communication channel in the workplace.

Integrating the 3 x 3 Writing Process

This mindboggling quantity of 3.2 million emails sent per second doesn’t necessarily mean that quality is a non-issue for email, however. Because it has, to some extent, replaced mailed letters for formal correspondence, emails related to important occasions such as applying for and maintaining employment must be impeccably well written. Your email represents you in your physical absence, as well as the company you work for if that’s the case, so it must be both good, well-written and appropriate.

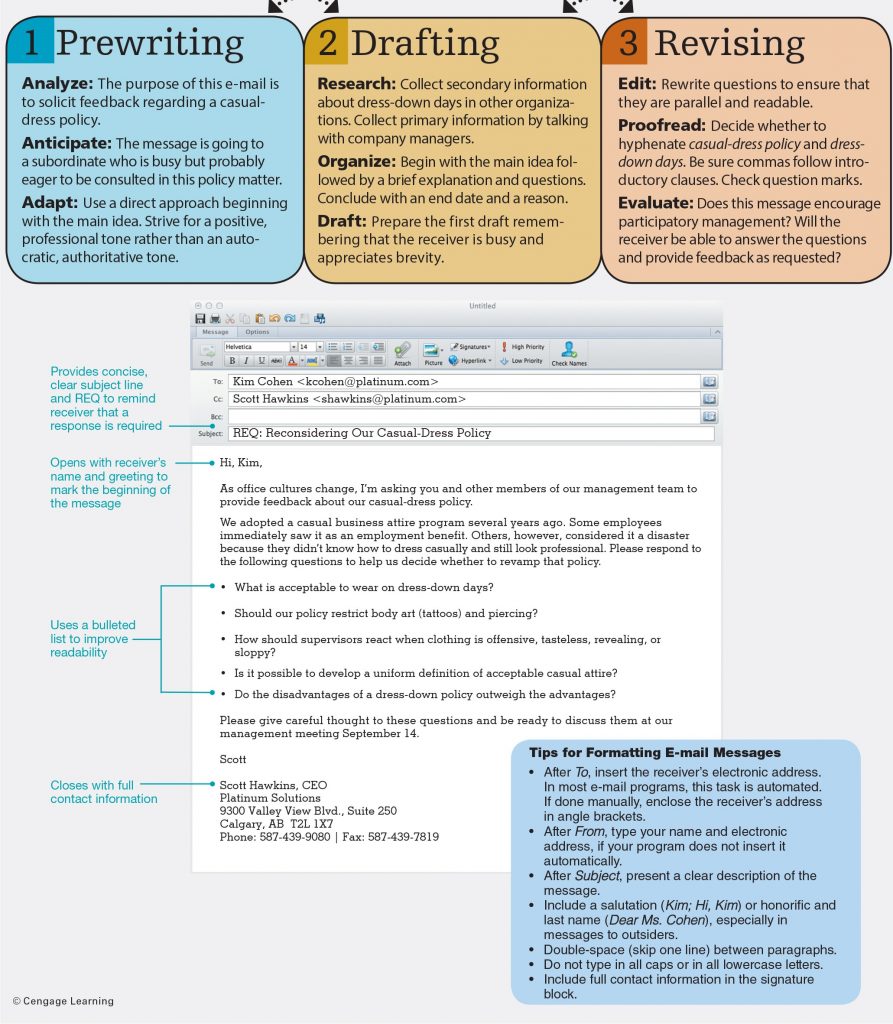

Begin by ensuring that you really need an email to represent you because emailing merely to avoid speaking in person or calling by phone can do more harm than good. If an email is necessary, however, then it must be effective. As people who make decisions about your livelihood, the employers and clients you email can be highly judgmental about the quality of your writing. To them, it’s an indication of your professionalism, attention to detail, education, and even intelligence. The writing quality in a single important email can be the difference between getting hired and getting fired or remaining unemployed. Using the 3 x 3 Writing Process (see Figure 18.1) gives you a road map to writing effective emails.

Structure and Content

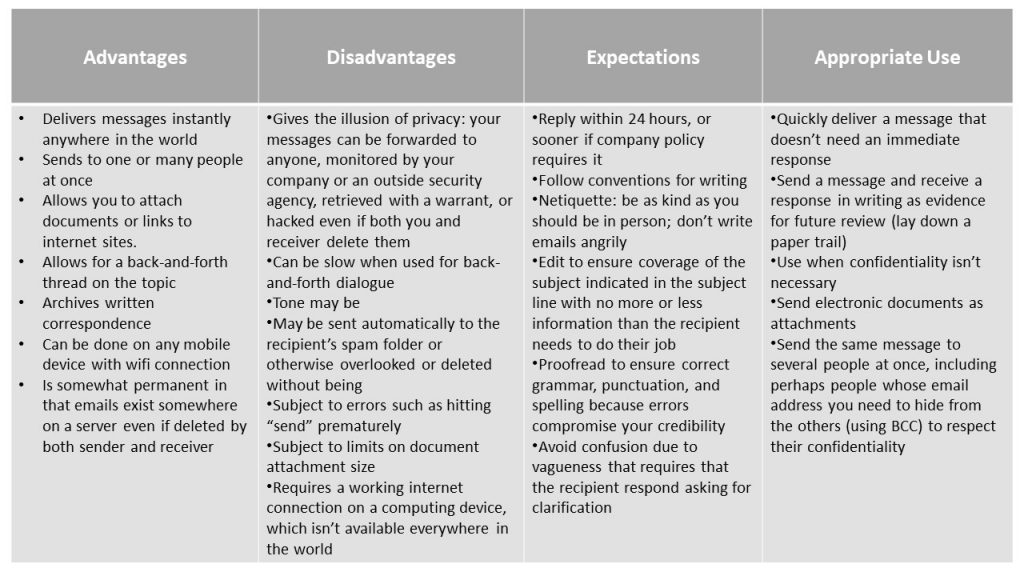

Before delving into the details of how to construct emails, let’s review the advantages, disadvantages, and occasions for their use.

Table 18.1 Excerpt: Email Pros, Cons, and Proper Use

Knowledge Check

Email Address

The first thing you see when an email arrives in your inbox is who it’s from. The address determines immediately how you feel about that email—whether excited, uninterested, curious, angry, hopeful, scared or just obliged to read it. Your email address will create similar impressions on those you email depending on your relationship with them. It’s therefore important that you send from the right email address.

If you work for a company, obviously you must use your company email address for company business. Customers expect it. Bear in mind that in a legal and right-to-privacy sense, you don’t own these emails. If they exist on a company server, company administrators can read any email they are investigating a breach of company policy or criminal activity (Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, 2010). This means that you must be careful not to write anything in an email that could compromise your employability.

If you’re writing on your own behalf for any business or job-application purposes, it’s vital that you have a respectable-looking email address. Using a college or university email is a good bet because it proves that you indeed are attending or attended a post-secondary institution when you’ve made that claim in your application. If your name is Justin Trudeau, for instance, your ideal email address would simply be justin.trudeau@ with one of the major email providers like Gmail or Outlook/Hotmail.

What’s fundamentally important, however, is that you retire your teenage joke email address. If you have one of these, now that you’re an adult, it will only do irreparable harm to your employability prospects if you’re using it for job applications. Any potential employer or other professional who gets an email from pornstar6969baby@whatever.com is going to delete it without even opening it.

Also, just as your demeanour and language style changes in social, family, and professional contexts, you should likewise hold multiple email accounts—one for work, one for school, and one for personal matters. Each of the 3.8 billion email users in the world has an average of 1.7 email accounts (Radicati, 2017). It’s likely that you will have more than three throughout your life and retire accounts as you move on from school and various workplaces. If you can manage it, you can set up forwarding so that you can run multiple accounts out of one, except where company or institutional policy requires that you work entirely within a designated email provider or client.

Timestamp & Punctuality

The timestamp that comes with each email means that punctuality matters and raises the question of what the expectations are for acceptable lag time between you receiving an email and returning an expected response. Of course, you can reply as soon as possible as you would when texting and have a back-and-forth recorded in a thread. What if you need more time, however?

Though common wisdom used to be that the business standard is to reply within 24 hours, the availability of email on the smartphones that almost everyone carries in their pockets has reduced that expectation to a few hours. Recent research shows that half of email responses in business environments in fact comes within two hours (Vanderkam, 2016). Some businesses have internal policies that demand even quicker responses because business moves fast. If you can get someone’s business sooner than the competition because you reply sooner, then of course you’re going to make every effort to reply right away. Of course, the actual work you do can get in the way of email, but you must prioritize incoming work in order to stay in business.

What if you can’t reply within the expected number of hours? The courteous course of action is to reply as soon as possible with a brief message saying that you’ll be turning your attention to this matter as soon as you can. You don’t have to go into detail about what’s delaying you unless it’s relevant to the topic at hand, but courtesy requires that you at least give a timeline for a fuller response and stick to it.

Subject Line

The next most important piece of information you see when scanning your inbox is the email’s subject line. The busy professional who receives dozens of emails each day prioritizes their workload and response efforts based largely on the content of the subject lines appearing in their inbox. Because the subject line acts as a title for the email, the subject line should accurately summarize its topic in 3-7 words.

The wordcount range here is important because your subject line shouldn’t be so vague that its one or two words will be misleading, nor so long and detailed that its eight-plus words will be cut off by your inbox layout. Though it must be specific to the email topic, details about specific times and places, for instance, should really be in the message itself rather than in the subject line (see Table 18.2 below). Also, avoid using words in your subject line that might make your email look like spam. A subject line such as Hello or That thing we talked about might appear to be a hook to get you to open an email that contains a malware virus. This may prompt the recipient to delete it to be on the safe side, or their email provider may automatically send it to the junkmail box, which people rarely check. It will be as good as gone, in any case.

Table 18.2: Subject Line Length

| Too Short | Just Right | Too Long and Detailed |

| Problem | Problem with your product order | Problem with your order for an LG washer and dryer submitted on April 29 at 11:31 p.m. |

| Meeting | Rescheduling Nov. 6 meeting | Rescheduling our 3 p.m. November 6 meeting for 11am November 8 |

| Parking Permits | Summer parking permit pickup | When to pick up your summer parking permits from security |

Stylistically, notice that appropriately sized subject lines typically abbreviate where they can and avoid articles (the, a, an), capitalization beyond the first word (except for proper nouns), and excessive adjectives.

Whatever you do, don’t leave your subject line blank. Even if you’re just firing off a quick email to send an attachment to yourself, the subject line text will be essential to your ability to retrieve that file later. Say you find yourself desperately needing that file months or even years later because the laptop it was saved on was stolen or damaged beyond repair, which you couldn’t have predicted at the time you sent it. A search in your email provider for words matching those you used in the subject line will quickly narrow down the email in question. Without words in the subject line or message, however, you’ll have no choice but to guess at when you sent the email and waste time going through page after page of sent-folder messages looking for it. A few seconds spent writing a good subject line can potentially save hours of frustrating searches.

Knowledge Check

Opening Salutation & Recipient Selection

When a reader opens your email, its opening salutation indicates not only who the message is for but also its level of formality. As you can see in Table 18.3 below, opening with Dear [Full Name] or Greetings, [Full Name]: strikes an appropriately respectful tone when writing to someone for the first time in a professional context. When greeting someone you’ve emailed before, Hello, [First name]: maintains a semiformal tone. When you’re more casually addressing a familiar colleague, a simple Hi [First name], is just fine.

Table 18.3: Opening Salutation Examples

| First-time Formality | Ongoing Semiformal | Informal |

| Dear Ms. Melody Nelson: Dear Ms. Nelson: Greetings, Ms. Melody Nelson: Greetings, Ms. Nelson: |

Hello, Melody: Hello again, Melody: Thanks, Melody. (in response to something given) |

Hi Mel, Hey Mel, Mel, |

Notice that the punctuation includes a comma after the greeting word and a colon after their name for formal and semiformal occasions. Informal greetings, however, relax these rules by omitting the comma after the greeting word and replacing the colon with a comma. Don’t play it both ways with two commas; Hi, Jeremy, appears too crowded with them.

Depending on the nature of the message, you can use alternative greeting possibilities. If you’re thanking someone for information they’ve sent you, you can do so right away in the greeting; e.g., Many thanks for the contact list, Maggie. When your email exchange turns into a back-and-forth thread involving several emails, it’s customary to drop the salutation altogether and treat each message as if it were a text message even in formal situations.

Formality also dictates whether you use the recipient’s first name or full name in your salutation. If you’re writing to someone you know well or responding to an email where the sender signed off at the bottom using their first name, they’ve given you the green light to address them by their first name in your response. If you’re addressing someone formally for the first time, however, strike an appropriately respectful tone by using their full name. If you’re addressing a group, a simple Hello, all: or Hello, team: will do.

Be careful when selecting recipients. First, spell their name correctly because email addresses often have non-standard combinations of name fragments and numbers; any typos will result in the server bouncing your email back to you as being unsent. Wait before entering their name in the recipient or “To” field in case you accidentally hit the Send button before you’re finished drafting your email. If you prematurely send an email, immediately send a quick follow-up apologizing for the confusion and the completed message. Another preventative measure is to compose a message offline, such as in an MS Word or simple Notepad document devoid of formatting, then copy and paste it into the email field when you’re ready to send.

If you have a primary recipient in mind but want others to see it, you can include them in the CC (carbon/complimentary copy) line. (If confidentiality requires that recipients shouldn’t see one another’s addresses, BCC [blind carbon copy] them instead). Be selective with whom you CC. Yes, it’s good to keep your manager in the loop, but you may want to do this only at the beginning and the end of a project’s email “paper” trail. They will appreciate that things are underway and wrapping up but may get annoyed if their inbox is flooded with every little mundane back-and-forth throughout the process. If in doubt, speak with your manager about their preferences for being CC’d.

Never “reply all” so that everyone included in the “To” line and CC’d sees your reply unless your response includes information that everyone absolutely must see. Bear in mind that, concerning email security, no matter who you select as the primary or secondary (CC’d) recipients of your email, always assume that it may be forwarded on to other people, including those you might not want to see it. Emails are not private. You have no control over whether the recipients will forward an email on to others , and if your email contains any legally sensitive content, it can even be retrieved from the server storing it with a warrant from law enforcement. A good rule of thumb is to never send an email that you would be embarrassed by if it were read by your boss, your family, or a jury. No technical barriers prevent it from falling into their hands.

Message Opening

Most emails will be direct-approach messages where you get right to the point in the opening sentence immediately below the opening salutation. As we saw in unit 11 on message organization, the direct-approach pattern does the reader a favour by not burying the main point under a pile of contextual background. If you send a busy professional on a treasure hunt for your main point, a request for information for example, don’t blame them if they don’t find it and don’t provide the information you asked for. They might have given up before they got there or missed it when skimming, as busy people tend to do. By stating in the opening exactly what you want the recipient to do, however, you increase your chances of achieving that goal.

Table 18.4 Direct- vs. Indirect-approach Email Openings

| Sample Direct Opening | Sample Indirect Opening |

| We have reviewed your application and are pleased to offer you the position of retail sales manager at the East 32nd and 4th Street location of Swansong Clothing. | Thank you very much for your application to the retail sales manager position at the East 32nd and 4th Street location of Swansong Clothing. Though we received a large volume of high-quality applications for this position, we were impressed by your experience and qualifications. |

Indirect-approach emails should be rare and only sent in extenuating circumstances. Using email to deliver bad news or address a sensitive topic can be seen as a cowardly way of avoiding difficult situations that should be dealt with in person or, if the people involved are too far distant, at least by phone. Other circumstances that might force you to use the indirect approach for emails include the following:

- Needing to use persuasive techniques

- Having no other means of contacting the recipient

- Needing to get the email exchange in writing in case the situation escalates and must be handled as evidence by higher authorities

- Needing to deliver a large number of bad-news messages without having the time or resources to individually customize each, such as when you are sending rejection notices to job applicants (see the sample indirect opening in Table 18.4 above); out of expedience, it’s understandable if these are boiler-plate responses

In such cases, the indirect approach means that the opening should use buffer strategies to ease the recipient into the bad news or set the proper context for discussing the sensitive topic.

Otherwise, your email must pass the first-screen test, which is that everything the recipient needs to see is visible in the opening without forcing them to scroll further down for it. Before pressing the Send button, put yourself in your reader’s shoes and consider whether your message passes the first-screen test. If not, and if you have no good reason to take the indirect approach, then re-organize your email message by moving (copying, cutting, and pasting, or ctrl. + C, ctrl. + X, ctrl. + v) its main point up to make it the opening of your message.

Knowledge Check

Message Body

Emails long enough to divide into paragraphs follow the three-part message organization where the message body supports the opening main point with explanatory details such as background information justifying an information request. With brevity being so important in emails, keeping the message body concise, with no more information than the recipient needs to do their job, is extremely important to the message’s success. The message body, therefore, doesn’t need proper three-part paragraphs. In fact, one-sentence paragraphs (single spaced with a line of space between each) and bullet-point lists are fine. If your message grows in length beyond the first screen, document design features such as bold headings help direct readers to the information they need. If your message gets any larger, moving it into an attached document is better than writing several screens of large paragraphs. Unlike novels, people don’t enjoy reading emails per se.

Also keep email messages brief by sticking to one topic per email. If you have a second topic you must cover with the same recipient(s), sending a separate email about it can potentially save you time if you need to retrieve that topic content later. If the subject line doesn’t describe the topic you’re looking for because it was a second or third topic you added after the one summarized in the subject line, finding that hidden message content will probably involve opening several emails. A subject line must perfectly summarize all of an email’s contents to be useful for archiving and retrieval, so sticking to one topic per email will ensure both brevity and archive retrieval efficiency.

Message Closing

An email closing usually includes action information such as direction on what to do with the information in the message above and deadlines for action and response. If your email message requests that its nine recipients each fill out a linked Doodle.com survey to determine a good meeting time, for instance, you would end by saying, Please fill out the Doodle survey by 4 p.m. Friday, May 18. If the message doesn’t call for action details, some closing thought (e.g., I’m happy to help. Please drop me a line if you have any questions) ends it without giving the impression of being rudely abrupt. Goodwill statements, such as Thanks again for your feedback on our customer service, are necessary especially in emails involving gratitude.

Closing Salutation

A courteous closing to an email involves a combination of a pleasant sign-off word or phrase and your first name. As with the opening salutation, closing salutation possibilities depend on the nature of the message and where you want to position it on the formality spectrum, as shown in Table 18.5 below.

Table 18.5: Closing Salutation Examples

| Formal | Semiformal | Informal |

| Best wishes, Kind regards, Much appreciated, Sincerely, Warm regards, |

Best, Get better soon, Good luck, Take care, Many thanks, |

All good things, Be well, Bye for now, Cheers, Ciao, |

Your first email to someone in a professional context should end with a more formal closing salutation. Later emails to the same person can use the appropriate semiformal closing salutation for the occasion. If you’re on friendly, familiar terms with the person but still want to include email formalities, an informal closing salutation can bring a smile to their face. Notice in Table 17.5 that you capitalize only the first word in the closing salutation and add a comma at the end.

Including your first name after the closing salutation ends in a friendly way as if to say, “Let’s be on a first-name basis” if you weren’t already, greenlighting your recipient to address you by your first name in their reply. In your physical absence, your name at the end is also a way of saying, like politicians chiming in at the end of campaign ads, “I’m [name] and I approve this message.” It’s a stamp of authorship. Omitting it gives the impression of being abrupt and too busy or important to stop for even a second of formal niceties.

E-signature

Not to be confused with an electronic version of your handwritten signature, the e-signature that automatically appears at the very bottom of your email is like the business card you would hand to someone when networking. Every professional should have one. Like a business card, the e-signature includes all relevant contact information. At the very least, the e-signature should include the details given in Table 18.6 below.

Table 18.6: E-signature Part

| E-signature Parts | Examples |

|---|---|

| Full Name, Professional Role Company Name Company address Phone Number(s) Company website, Email address |

Jessica Day, Graphic Designer UXB Designs 492 Atwater Street Toronto, ON M4M 2H4 416-555-2297 (c) uxb.com | jessica.day@uxb.com |

| Full Name, Credentials Professional Role Company Name Company Address Phone Number(s) Company website, email address |

Winston Schmidt, MBA Senior Marketing Consultant Tectonic Global Solutions Inc. 7819 Cambie Street, Vancouver, BC V5K 1A4 604.555.2388 (w) | 604.555.9375 (c) tectonicglobal.com | m.bennington@tgs.com |

Depending on the individual’s situation, variations on the e-signature include putting your educational credentials after your name (e.g., MBA) on the same line and professional role on the second line, especially if it’s a long one, and the company address on one line or two. Also, those working for a company usually include the company logo to the left of their e-signature. Some instead (or additionally) add their profile picture, especially if they work independently, though this isn’t always advisable because it may open you to biased reactions. Other professionals add links to their social media profiles such as LinkedIn and the company’s Facebook and Twitter pages. For some ideas on what your e-signature could look like, simply image-search “email e-signature” in your internet browser’s search engine.

If you haven’t already, set up your e-signature in your email provider’s settings or options page. In Gmail, for instance, click on the settings cog icon at the top right, select Settings from the dropdown menu, scroll down the General tab, and type your e-signature in the Signature field. Make absolutely sure that all of the details are correct and words spelled correctly. You don’t want someone to point out that you’ve spelled your professional role incorrectly after months of it appearing in hundreds of emails.

Attachments

Email’s ability to help you send and receive documents makes it an indispensable tool for any business. Bear in mind a few best practices when attaching documents:

- Always announce an attachment in an email message with a very brief description of its contents. For instance, Please find attached the minutes from today’s departmental meeting might be all you write between the opening and closing salutations.

- Never leave a message blank when attaching a document in an email to someone else. Your message should at least be like the one given above. Of course, including a message is up to you if you’re sending yourself an attachment as an alternative to using a dedicated cloud storage service like Google Drive or Microsoft OneDrive. Even if it’s just for yourself, however, at least including a subject line identifying the nature of the attachment will make locating the file easier months or even years later.

- Ensure that your attachment size, if it’s many megabytes (MB), is still less than your email provider’s maximum allowable for sending and receiving. Gmail and Yahoo, for instance, allow attachments up to 25 MB, whereas Outlook/Hotmail allow only 10 MB attachments. However, files that are gigabytes (GB) large can be shared by using email to permit access to them where they’re hosted in cloud storage services such as Google Drive, Microsoft OneDrive, Dropbox, and many others that have varying limits from 5 GB for no-cost to 10 TB for paid storage (Khanna, 2017).

- Always check to ensure that you’ve attached a document as part of your editing process. It shows that you lack attention to detail if your recipient responds to remind you to attach the document. Some of the more sophisticated email providers will remind you to do this when you hit the Send button if you’ve mentioned an attachment in your message but haven’t yet actually attached it. If you get into the habit of relying on this feature in one of your email providers (e.g., your personal Gmail account) but are on your own in others (e.g., your work or school email provider), the false sense of security can hurt you at some point when using the latter.

Before Sending Your Email

Before hitting the send button, follow through on the entire writing process, especially the Editing stage with its evaluation, revision, and proofreading sub-stages. Put yourself in your reader’s position and assess whether you’ve achieved the purpose you set out to achieve in the first place. Evaluate also if you’ve struck the appropriate tone and formality. If you’re aware that your tone is too angry, for instance, save the message in the drafts folder and take time to cool down by focusing on other business for a while. When you come back to your email draft the next day, you will usually find that you don’t feel as strongly about what you wrote the day before. Review the advice about netiquette in section 6.2, then replace the angry words with more carefully chosen expressions to craft a more mature response before hitting the send button. You’ll feel much better about this in the end.

After revising generally, always proofread an email. In any professional situation, but especially in important ones related to gaining and keeping employment, any typo or error related to spelling, grammar, or punctuation can cost you dearly. A poorly written email is insulting because it effectively says to the recipient: “You weren’t important enough for me to take the time to ensure that this email was properly written.” Worse, poor writing can cause miscommunication if it places the burden of interpretation on the reader to figure out what the writer meant to say if that’s not clear. If the recipient acts on misinterpretations, and others base their actions on that action, you can soon find that even small errors can have damaging ripple effects that infuriate everyone involved.

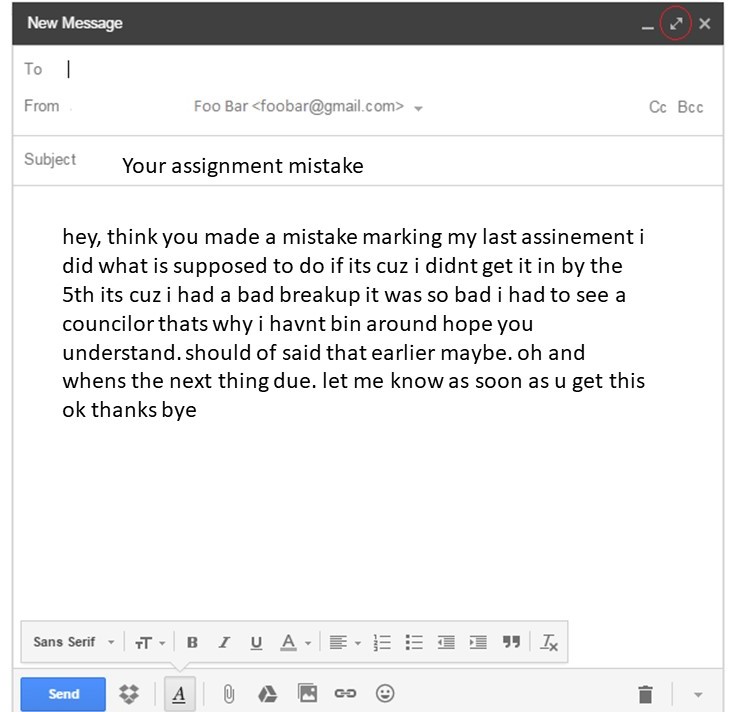

Sample 1: Review the following poorly written email.

Sample 1: Review the following poorly written email.

Analysis: The poorly written draft has the look of a hastily and angrily written text to a “frenemy.” An email to a superior, however, calls for a much more formal, tactful, courteous, and apologetic approach. The undifferentiated wall of text that omits or botches standard email parts such as opening and closing salutations is the first sign of trouble. The lack of capitalization, poor spelling (e.g., councilor instead of counsellor), run-on sentences and lack of other punctuation such as apostrophes for contractions, as well as the inappropriate personal detail all suggest that the writer doesn’t take their studies seriously enough to deserve any favours. Besides tacking on a question at the end, one that could be easily answered by reading the syllabus, the writer is ultimately unclear about what they want; if it’s an explanation for why they failed, then they must be upfront about that. The rudeness of the closing is more likely to enrage the recipient than get them to deliver the requested information.

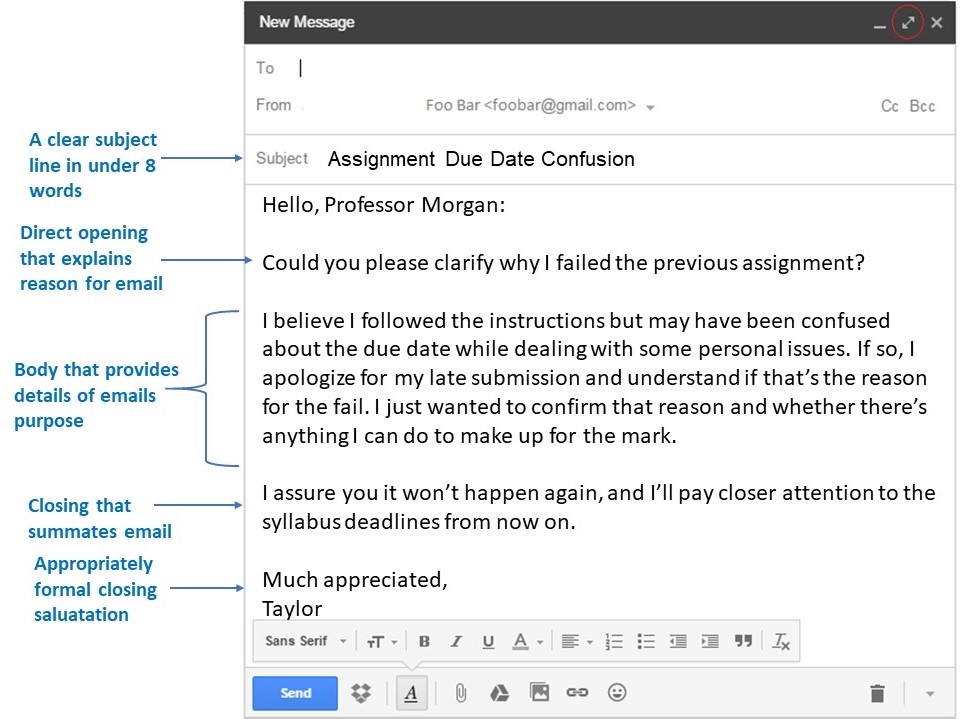

Sample 2: Now review the revised email.

Analysis: The improved version stands a much better chance of a sympathetic response. It corrects the problems of the first draft starting with properly framing the message with expected formal email parts. It benefits from a more courteous tone in a message that frontloads a clear and polite request for information in the opening. The supporting detail in the message body and apologetic closing suggests that the student, despite their faults, is well aware of how to communicate like a professional to achieve a particular goal.

After running such a quality-assurance check on your email, your final step before sending it should involve protecting yourself against losing it to a technical glitch. Get in the habit of copying your email message text (ctrl. + A, ctrl. + C) just before hitting the Send button, then checking your Sent folder immediately to confirm that the email sent properly. If your message vanished due to some random malfunction, as can happen occasionally, immediately open a blank MS Word or Notepad document and paste the text there (ctrl. + V) to save it. That way, you don’t have to waste five minutes rewriting the entire message after you solve the connectivity issues or whatever else caused the glitch.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/how-to-write-and-send-professional-email-messages-2061892_FINAL-5b880103c9e77c0025a29ec4.png)

For similar views on email best practices, see Guffey, Loewy, and Almonte (2016, pp. 90-97), which furnished some of the information given above.

Key Takeaway

Follow standard conventions for writing each part of a professional or academic email, making strategic choices about the content and level of formality appropriate for the audience and occasion.

Follow standard conventions for writing each part of a professional or academic email, making strategic choices about the content and level of formality appropriate for the audience and occasion.

Exercises

1. Take one of the worst emails you’ve ever seen. It could be from a friend, colleague, family member, professional, or other.

1. Take one of the worst emails you’ve ever seen. It could be from a friend, colleague, family member, professional, or other.

i. Copy and paste it into a blank document, but change the name of its author and don’t include their real email address (protect their confidentiality).

ii. Use MS Word’s Track Changes comment feature to identify as many organizational errors as you can.

iii. Again using Track Changes, correct all of the stylistic and writing errors.

2. Let’s say you just graduated from your program and have been putting your name out there, applying to job postings, networking, and letting friends and colleagues know that you’re on the job market. You get an email from someone named Dr. Emily Conway, the friend of a friend, who needs someone to put together some marketing brochures for her start-up medical clinic in time for a conference in a week. It’s not entirely what you’ve been training to do, but you’ve done something like it for a course assignment once, and you need rent money, so you decide to accept the offer. Dr. Conway’s email asks you five questions in the message body:

i. Our mutual friend mentioned you just graduated from college. What program? How’d you do?

ii. Can you send a sample of your marketing work?

iii. How much would you charge for designing a double-sided 8½x11″ tri-fold brochure?

iv. When you’ve completed your design, would you be okay with sending me the ready-to-print PDF and original Adobe Illustrator file?

v. If I already have all the text and pictures, how soon can you do this? Can you handle the printing as well?

Dr. Conway closes her email asking if you’d like to meet to discuss the opportunity in more detail and signs off as Emily. Draft a formal response email that abides by the conventions of a formal email.

References

Doyle, A. (2019). How to write and send professional email messages [Infographic]. Thebalancecareers. Retrieved from https://www.thebalancecareers.com/how-to-write-and-send-professional-email-messages-2061892

Guffey, M., Loewy, D., & Almonte, R. (2016). Essentials of Business Communication (8th Can. ed.). Toronto, Nelson.

Guffey, M., Loewry, D., & Griffin, E. (2019). Business communication: Process and product (6th ed.). Toronto, ON: Nelson Education. Retrieved from http://www.cengage.com/cgi-wadsworth/course_products_wp.pl?fid=M20b&product_isbn_issn=9780176531393&template=NELSON

Khanna, K. (2017, March 25). Attachment size limits for Outlook, Gmail, Yahoo, Hotmail, Facebook and WhatsApp. The Windows Club. Retrieved from http://www.thewindowsclub.com/attachment-size-limits-outlook-gmail-yahoo

Klockars-Clauser, S. (2010, March 26). Flaming computer – “don’t panic” (4549185468). Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flaming_computer_-_%22don%27t_panic%22_(4549185468).jpg

MindToolsVideos. (2018). 6 steps for writing effective emails [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y50xhHQ8Qf0&feature=emb_logo

Neel, A. (2017, March 7). Follow your passion. Unsplash. Retrieved from https://unsplash.com/photos/QLqNalPe0RA

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada. (2010, July 21). Collection and use of employee’s email deemed acceptable for purposes of investigating breach of agreement. Retrieved from https://www.priv.gc.ca/en/opc-actions-and-decisions/investigations/investigations-into-businesses/2009/pipeda-2009-019/

The Radicati Group. (2017, January). Email statistics report, 2017-2021. Palo Alto, CA: The Radicati Group, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.radicati.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Email-Statistics-Report-2017-2021-Executive-Summary.pdf

Rawpixel. (2018, March 28). Person using MacBook Pro on brown wooden desk 1061588. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/person-using-macbook-pro-on-brown-wooden-desk-1061588/

Tumisu. (2017, December 14). Contact us contact email phone mail inbox. Retrieved from https://pixabay.com/en/contact-us-contact-email-phone-2993000/

Vanderkam, L. (2016, March 29). What is an appropriate response time to email? Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/3058066/what-is-an-appropriate-response-time-to-email