6. Project Execution

Overview

Each project is unique because they come in all different shapes and sizes. During implementation, the unique product/service/result is created. The nature of the work carried out during implementation is very different for each project. For instance, in technology projects, the phase involves developing, testing, and deploying a new application. Implementation may occur through a single release or multiple releases. Projects intending to identify new potential export markets will carry out their research plans during the implementation phase. The result of such work may be a research report with recommendations for the organization’s senior executives. Similarly, a project seeking to develop new employee orientation materials may develop an orientation manual and/or a training program during implementation. Naturally, the tools and techniques used for these two projects will be very different. Rather than attempting to describe all the potential tools and techniques that could be used during implementation of different projects, an overview of the nature of this phase will be discussed.

The plans developed by the project team are put into motion during implementation. The team is drawing on the plans they created to design their solution(s), manage project resources, timelines, costs, risks, procurement, quality, stakeholders, and communications.

Project implementation is usually where the project team spends most of their time. As a result, this is typically where the majority of the project’s budget is spent. Effective communication is critical during implementation as there are many small teams focused on producing deliverables which often have many team interdependencies. The deliverables of the project include all of the products, services, and results created to fulfill the project’s objectives, including all the project management documents.

During implementation, as tasks are carried out, progress information is being reported through regular team meetings. Again, effective communication becomes critical. Depending on the nature of the project, these team meetings could be daily, weekly, or monthly. Team meeting frequency is a decision made by the project leader based on which is the most effective at keeping everyone informed and aligned with the work underway.

The project leader uses performance information to ensure communication channels remain open, issues are identified, and corrective action is taken as needed. When predictive/waterfall development methodology is used, the implementation phase may identify the need for a number of change requests. Change requests occur when the project team discovers a new requirement and/or a way to improve the project’s outcomes.

Lastly, one of the universal factors associated with successful project implementations is successful team management. The key tools and techniques used in team management will be explored in detail in the section below.

6.1 Managing Teams

The project team is often made up of people supporting the project on a full-time and part-time basis. The team members may be temporarily assigned to the project from other internal functions within the organization or brought into the organization specifically for the project. Regardless of their source, it is critical to invest time and effort into developing a high-performing project team composed of skilled and motivated individuals who can contribute to the project’s success. One of the many responsibilities of a project leader is to enhance the abilities of each project team member by fostering individual growth and accomplishment. At the same time, everyone must be encouraged to share ideas and work with others toward a common goal.

Determining when a team is needed is an important first step. Assigning a team is a better approach than assigning individuals when:

- When no single person has the knowledge, skills, and abilities to either understand or solve the problem

- When innovation is important

- When multiple individuals must be committed to identifying and implementing a solution (commonly referred to as “getting buy-in”)

- When the problem and solution cross-project/organizational functions

Individuals can outperform teams on some occasions. An individual tackling a problem consumes fewer resources than a team and can operate more efficiently—as long as the solution meets the project’s needs. A person is most appropriate in the following situations:

- When a single person has the knowledge, skills, and resources to solve the problem

- When speed is important

- When the activities involved in solving the problem are very detailed

- When documents need to be written (teams can provide input, but writing is a solitary task)

In addition to knowing when a team is appropriate, the project leader must also understand what type of team will function best for the project’s needs.

Functional Teams

A functional team refers to one of the project’s functions, such as the engineering team, the procurement team, and the communications team. Any one of these teams may be tasked with solving a nuanced problem on a project. For example, low stakeholder engagement may be a problem addressed by the communications team. Another example would be the procurement team initiating a resolution with a vendor who is not meeting the expectations of a contract.

When a functional team is assigned to lead the resolution of a problem or the pursuit of an opportunity, they are likely to do some initial analysis internally and then share it with the broader project team. This is often necessary because the work on a project must be integrated and a single functional team is unlikely to resolve complex issues and/or pursue opportunities on their own.

Cross-Functional Teams

Cross-functional teams are utilized when issues and/or work processes require collaboration between two or more of the project’s functional teams. The team members are selected to bring their functional expertise to address project challenges and opportunities. Given the far-reaching nature of change initiatives today, most projects require cross-functional teams. This is true regardless of the development methodology used. More information on the nature of an agile team’s composition will be covered later in the chapter.

Problem-Solving Teams

Problem-solving teams are assigned to address specific issues that arise during the life of the project. The project leadership includes members with the expertise required to address the problem. The team is chartered to address that problem and then disband. As such, they are more temporary than functional and cross-functional teams.

Projects are unique and temporary. The staffing model employed is also unique and temporary. This gives rise to a number of unique challenges:

- Project team members who are “borrowed” and do not report to the project leader in the long term may have their priorities elsewhere

- They may be juggling many projects as well as their full-time functional job, causing them difficulty in meeting deadlines

- Project leaders may find out about missed deadlines after it is too late to recover

- Personality conflicts may arise (e.g. differences in social style/values, bitterness between team members who have worked on past projects together, etc.)

- Since team members know the project team is not their long-term “home,” conflict resolution can be more challenging

Leadership Styles

Just as organizations rise and fall on the capabilities of their leaders, projects rise and fall on the capabilities of project leaders.

“Leader” versus “Manager”

The two dual concepts, leader and manager, are not interchangeable, nor are they redundant. The differences between the two can, however, be confusing. In many instances, in order to be a good manager, one also needs to be an effective leader. Many people hope that their leadership skills, their ability to formulate a vision and get others to “buy into” that vision, will propel the team forward. However, effective leadership often necessitates the ability to manage—to set goals; plan, devise, and implement strategy; make decisions and solve problems; organize and control. Essentially, project leaders need to be effective managers and effective leaders.

Much research has been published about leadership due to how crucial competent leaders are to organizational success. Leadership will continue to be in the spotlight for the foreseeable future. Disruptive technology, such as artificial intelligence, challenges our notions of what leaders are and what they do. Further, economies and societies continue to be deeply challenged by health, political, and environmental crises. When a crisis strikes, we look to leaders to help us navigate the ensuing chaos. With so much focus on leadership, studying leadership styles is a helpful starting place for students seeking to understand how successful people can introduce change into an organization. As we reflect on the various leadership styles, it also provides the student with an opportunity for self-reflection.

It is important to begin by noting that no particular leadership approach is appropriate for managing all projects. Due to the unique circumstances inherent in each project, the leadership approach and the management skills required for success will vary.

In addition, throughout a project, each stage may require a different leadership style. For instance, during the start-up phase of a project when new team members are first assigned to the project, a more command-and-control leadership style may be most effective. This is because the team is looking for direction about their roles and responsibilities, as well as clarity about the objectives of the project. Later, as the project moves into the planning stage where more conceptual work is being carried out causing creativity to become crucial, a transformational leadership style may be appropriate.

Many organizations are no longer seeking a fixed recipe for achieving organizational success. Agility is critical for organizations to survive and thrive in these unpredictable, turbulent times. Given this, a growing emphasis is being placed on the agile leader. “Agile” is a development methodology, but it is also a way of leading people and organizations.

Let us further define these leadership styles in order to understand their nature. This can lead to thought-provoking classroom discussions about the style of some of today’s most well-recognized leaders who have served as catalysts for change. In addition, by examining the nature and complexity profiles of different projects appropriate for each program of study, students can reflect on the application of various leadership styles in these projects.

Transactional Leaders:

Leaders who subscribe to the notion that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” are often described as transactional leaders. They are extremely task-oriented in their approach, frequently looking for incentives that will induce their followers into a desired course of action.1 These reciprocal exchanges take place in the context of a mutually interdependent relationship between the leader and the follower, frequently resulting in interpersonal bonding.2 The transactional leader moves a group toward task accomplishment by initiating structure and by offering an incentive in exchange for desired behaviours.

Transformational Leaders:

The transformational leader, on the other hand, moves and changes (fixes) things “in a big way!” Unlike transactional leaders, they do not cause change by offering incentives. Instead, they inspire others to action through their personal values, vision, passion, and belief in and commitment to the mission.3 Transformational leaders move others to follow through charisma (influence), individualized consideration (a focus on fostering personal growth in the follower), intellectual stimulation (questioning assumptions and challenging the status quo), and/or inspirational motivation (articulating an appealing vision). The transformational leader is a visionary leader. In short, leaders who are visionary are those able to influence followers through an emotional and/or intellectual attraction to the leader’s dreams for the future. Vision links a present and future state, energizes and generates commitment, provides meaning for action, and serves as a standard against which to assess performance.4 Evidence indicates that vision is positively related to follower attitudes and performance.5 Warren Bennis, widely regarded as a pioneer in the field of leadership, notes that a vision is effective only to the extent that the leader can communicate it in such a way that others come to internalize it as their own.6 Transformational leaders have engaging personalities characterized by extroversion, agreeableness, and openness to experience.7 They energize others. They increase followers’ awareness of the importance of the designated outcome.8 They motivate individuals to transcend their own self-interest for the benefit of the team and inspire organizational members to self-manage (become self-leaders).9 Transformational leaders move people to focus on higher-order needs (self-esteem and self-actualization). When organizations face a turbulent environment, such as intense competition or products that may quickly fall out of favour, they must act quickly. Since managers cannot rely solely on organizational structure to guide organizational activity, transformational leadership motivates followers into being fully engaged and inspired, internalize the goals and values of the organization, and move forward with dogged determination. Transformational leadership is positively related to follower satisfaction, performance, and acts of citizenship because transformational leaders’ behaviours elicit trust and perceptions of procedural justice (see Footnote 8). As noted by Pillai, Schriesheim, and Williams when followers perceive that they can influence the outcomes of decisions that are important to them and that they are participants in an equitable relationship with their leader, their perceptions of procedural justice [and trust] are likely to be enhanced (see Footnote 8).

Agile Leaders:

Note: Agile leadership should not be confused with agile development methodology.

Aaron De Smet, Michael Lurie, and Andrew St. George wrote in their 2018 McKinsey & Company article that agile leadership is about co-creation10. Agile leaders have made a fundamental shift by moving away from a reactionary approach and adopting a creativity-driven approach. At the heart of this shift in mindset is customer value, which is why agile leaders teach their teams how to focus on value creation. Agile leaders make the following shifts in mindset (see Footnote 10):

From certainty to discovery: fostering innovation

- A reactionary mindset of certainty is about playing not to lose, being in control, and replicating the past. Today, some leaders have shifted to a creativity-driven mindset of discovery which is about playing to win, seeking diversity of thought, fostering creative collision, embracing risk, and experimenting.

From authority to partnership: fostering collaboration

- This requires an underlying creativity-driven mindset of partnership and of managing by agreement based on freedom, trust, and accountability.

From scarcity to abundance: fostering value creation

- To deliver results, leaders must view the organization’s external environments with a creativity-driven mindset of abundance which recognizes the unlimited resources and potential available to their organizations in addition to enabling customer-centricity, entrepreneurship, inclusion, and cocreation.

One of the ways that project leaders can adopt an agile leadership style is by keeping the customer/user at the centre of the design. In addition, project success is dependent on value creation. Lastly, diverse opinions can be proactively sought out and the proposed value can undergo cost-benefit analysis.

As you reflect on the various leadership styles, keep in mind that project leaders must be able to adjust their leadership style to the needs of the organization and the project.

Leadership Skills

Project leaders require a diverse skill set, such as administrative skills, organizational skills, and any technical skills associated with accomplishing the project’s solution. In addition, a successful project leader has very strong problem-solving, negotiation, conflict management, and delegation skills. They possess a high degree of tolerance for ambiguity, utilize active listening techniques to promote healthy two-way communication, and are able to adjust their leadership style based on the state of affairs in the ever-changing project environment.

The types of skills and their respective depths are closely connected to the size and complexity profile of the project. Typically, on projects will smaller teams, project leaders require a greater degree of technical skill because they often have to be more hands-on in developing the schedule, cost estimates and quality standards. When these smaller teams are tackling complex solutions, the project leader needs to have a deeper level of technical understanding as they will be expected to guide the teams in this aspect. On projects with larger teams, a greater degree of organizational skills is required to ensure that the large number of project resources remain connected and aligned.

Problem-solving

In section 5.8, the cause-and-effect/fishbone diagram was introduced as a very effective quality management tool that can aid in the identification of the root cause of a problem. Project leaders who know how to use this tool are much more likely to identify why the team has run into problems and what should be done to resolve the issues permanently. This tool is most effective when used in team settings where people with subject matter expertise (relating to the problem) are the ones brainstorming the underlying drivers. For example, marketing experts analyzing why a promotional campaign failed to generate the expected level of incremental sales.

When the project team is underperforming, identifying the root causes is also important. This is more challenging for the project leader to do because the team’s performance problems may be a result of the project leader’s own skill deficiencies. For instance:

- Breakdown in team communication could represent a project leader’s lack of communication skills

- Uncommitted team members could represent a project leader’s lack of team-building skills

- Role confusion within the project team could represent a project leader’s lack of organizational skills

When these types of problems arise, project leaders must assess the performance of the team and their own performance. Seeking feedback from the team and other key stakeholders is an effective way to obtain the information required for root cause identification and self-reflection. Confidential surveys can be very helpful in this instance. In addition, high-performing project leaders often have a mentor that they go to for advice and support.

Negotiation

When multiple people are involved in an endeavour, differences in opinions and desired outcomes naturally occur. Negotiation is a process for developing a mutually acceptable outcome among parties in the presence of conflicting desired outcomes. A project leader will often negotiate with the project sponsor, resource managers, project team members, vendors, and other project stakeholders. Negotiation is an important skill when developing support for the project and preventing frustration among all parties involved, which could result in project failure.

Negotiations involve four principles:

- Separate people from the problem. Framing the discussions in terms of desired outcomes enables the negotiations to focus on finding solutions versus blaming.

- Focus on common interests. By avoiding the focus on differences, both parties are more open to finding solutions that are mutually beneficial.

- Seek options that advance shared interests. Once the common interests are understood, solutions that do not match with either party’s interests can be disregarded, while solutions that may serve both parties’ interests can be more deeply explored.

- Develop results based on standard criteria (for example, a standard criterion for a project developing a mobile application may be reaching 100,000 downloads in the App Store)Assuming that the parties have agreed on a common definition of project success, the selected criterion becomes a measure of when project success has been achieved.

For the project leader to successfully negotiate the project’s issues, they should be cognizant of the other party’s position. When negotiating with a key stakeholder, what is their concern or desired outcome? What are the important professional and personal factors for this stakeholder? Without this understanding, it is difficult to find a solution that will satisfy the stakeholder. While doing this, the project leader must also keep in mind which outcomes are desirable for the project. Typically, more than one outcome is acceptable. Successful negotiation starts with the desired outcomes. The interpersonal skills of the project leader are then put to the test as they work to reach a final agreement from all stakeholders on the most favourable outcomes.

Conflict Management

Counterintuitively, conflict on a project is necessary. There are many reasons why conflict occurs, such as ambiguity due to lack of information, personality differences, role confusion, differing ideas, timeline pressures, and clashes between individual versus team goals. Although good planning, communication, and team building can reduce the amount of conflict, conflict will still emerge. However, not all conflict is bad. A key benefit or outcome of conflict is that a team can learn to trust each other. Many teams are stronger because they have been able to successfully navigate conflict. In his bestselling book, The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni writes11:

“The first dysfunction is an absence of trust among team members. Essentially, this stems from their unwillingness to be vulnerable within the group. Team members who are not genuinely open with one another about their mistakes and weaknesses make it impossible to build a foundation for trust. This failure to build trust is damaging because it sets the tone for the second dysfunction: fear of conflict. Teams that lack trust are incapable of engaging in unfiltered and passionate debate of ideas. Instead, they resort to veiled discussions and guarded comments.”

Lencioni also asserts that, if a team does not work through its conflict and air its opinions through debate, team members will never really be able to buy in and commit to decisions (lack of commitment being Lencioni’s third dysfunction). Teams often have a fear of conflict to avoid hurting any team members’ feelings. The downside of this avoidance is that conflicts still exist under the surface and may resurface in more insidious and back-channel ways that can severely derail a team.

When conflict does arise on a project, project leaders must decide how to manage it. In their book Project Management: The Managerial Process, Erik Larson and Clifford Gray distinguish between functional and dysfunctional conflict12. Functional conflict helps the project team achieve the project objectives. Project leaders who want to harness the power of conflict for greater team effectiveness and productivity can intentionally invite functional conflict. They can do this by intentionally asking for diverse opinions, ensuring everyone participates in safe and open discussion spaces, and finding people willing to openly identify reasons why something may fail. As its name implies, dysfunctional conflict prevents the team from achieving project objectives. A common example of dysfunctional conflict is when personalities clash and the individuals are unable to communicate with each other and/or work together. Larson and Gray proposed five possible strategies for managing dysfunctional conflict:

- Mediating is the best approach when a conflict has turned into a “lose/lose” situation and the affected parties require assistance in facilitating a resolution. The project leader intervenes and tries to negotiate a resolution with the parties involved. This approach works well when the project leader has the time required to facilitate discussions and there is a chance that conflict resolution will serve as a learning opportunity for all parties involved.

- Arbitrating is the best approach when the project leader no longer believes that the parties can achieve resolution on their own and/or within the time available, so they must impose a solution. The project leader listens to the involved parties and then selects a solution that is in the best interest of the project and organization.

- Controlling the conflict is the best approach when parties will be able to attempt conflict resolution after they have had a chance to work through strong emotions. The project leader utilizes tactics to de-escalate the conflict’s intensity. For example, the affected parties may be asked to temporarily cease communication to allow each individual time for reflection and an opportunity to calm. If the parties are still unable to initiate conflict resolution, another strategy would be required.

- Accepting the conflict is the best approach when the relationship between the affected parties does not have long-term importance and/or the issue is of little significance to project success. In this situation, the project leader acknowledges the presence of conflict and intentionally allows it to continue.

- Eliminating the conflict is the best approach when all other approaches have failed. It requires one or all of the affected parties to be removed from the project team.

In conclusion, each of these approaches can be effective and useful depending on the situation. Project leaders will use each of these conflict resolution approaches depending on their personal approach and an in-depth assessment of the situation.

Project leaders will encounter a variety of individual responses to conflict within their team. Hanna Inam, a thought leader in transformational and agile leadership, purports that the basis of our reactions is often the only thing that can be seen.13 This includes an individual’s behaviours and the point of view/positions they take during discussions. However, it is important to learn about an individual’s underlying assumptions and aspirations (what they deem important) before jumping to conclusions and engaging in dysfunctional conflict.

Inam advocates for effective team building early on in a project and recommends that individuals take the time to get to know each other. She offers five simple questions to facilitate meaningful dialogue:

- What are your most important goals?

- How do you like to communicate?

Note: this goes beyond the devices one uses to communicate; it encompasses how a person verbalizes and understands information - What energizes you?

- What frustrates you?

- How can we best work together?

Notice how the first four questions are not about the project or teamwork, it is about life in general. Successful teams consist of members who understand their teammates’ personal and professional styles.

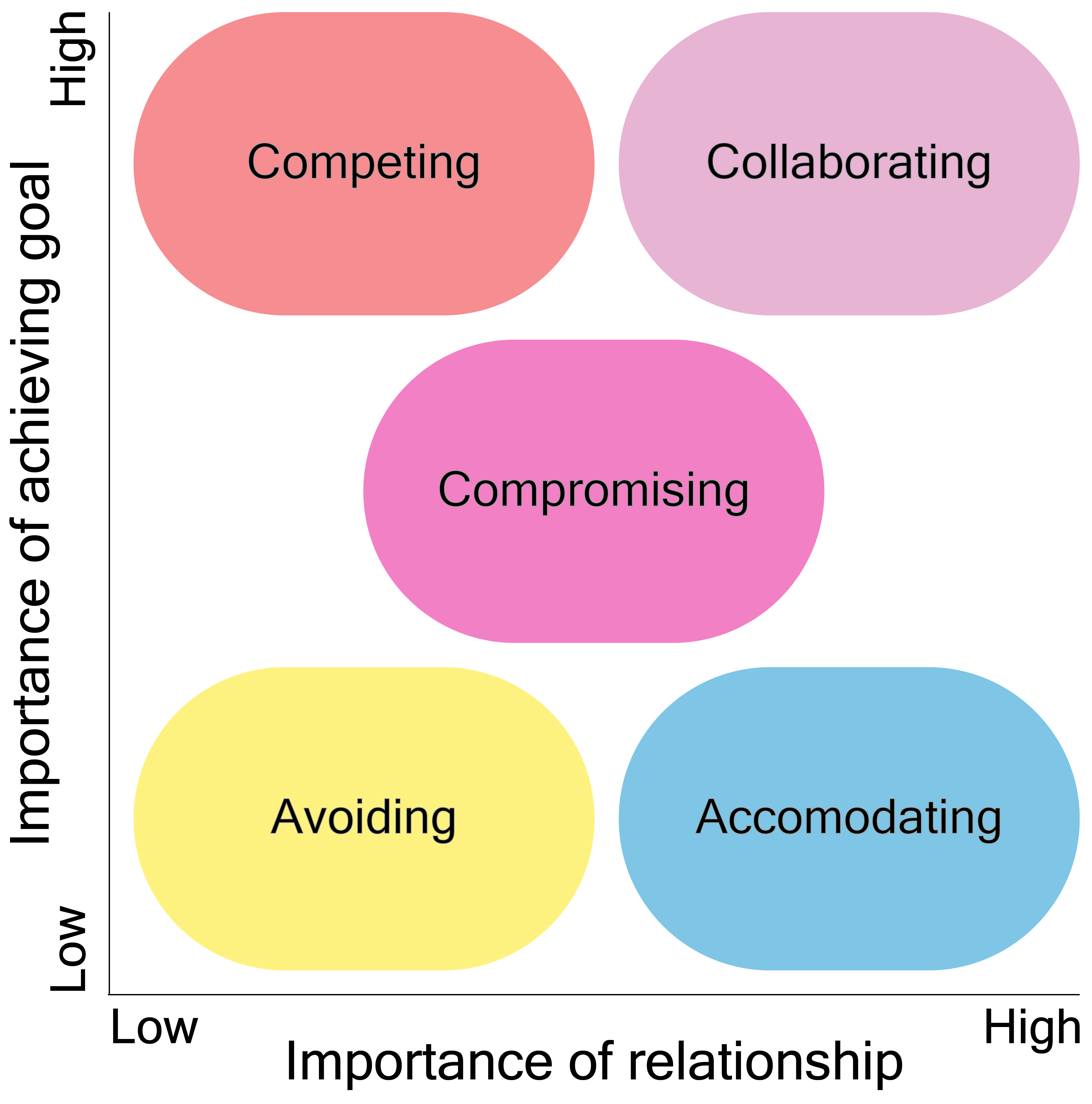

Inam also recommends that individuals learn their default conflict style and recognize that the same style does not work in every situation. The figure below is a summary of the five conflict styles:

| Avoiding | You decide that staying engaged in the conflict will not result in a good outcome |

| Accommodating | You view support towards others as low-cost to you and high-benefit to them |

| Competing | You view yourself as possessing greater expertise or better information than others |

| Compromising | You realize that each team member has to give something up because getting everyone’s needs met is unrealistic |

| Collaborating | You have needs that you want met but you also want to make sure the needs of others are met |

Note: the primary difference between compromising and collaborating is that collaboration does not result in having to give things up. The best outcome is achievable because there has been an open flow of communication and idea-sharing from the onset of the project or task.

Exhibit 6.1: A matrix displaying where the different conflict styles fall based on the importance they place on relationships versus achieving goals.

In summary, conflict can be uncomfortable and awkward, but it is important. Surfacing areas of conflict and differing perspectives can have a very positive impact on the growth and future performance of the team, and it should be managed constructively.

Delegation

Many people new to leadership have a difficult time entrusting others with work. Oftentimes, this occurs because the individual prefers to do the tasks independently as it may give them a sense of accomplishment. Regardless of the reason, it is disastrous for them and the team. 21st-century leadership requires leaders to determine which skills and experiences are required and when they are required. Delegation is also about setting up autonomous teams in a clear, empowering structure that facilities collaborative approaches to getting the work done. When the right people have been recruited for the project, it is critical that the project leader empowers people to take accountability and work collaboratively.

If the project leader delegates too little accountability to others to make decisions and act, the lack of creativity in the solution and lags in decision-making may prevent the project from delivering organizational value. On the other hand, delegating too much authority to others without the required knowledge, skills, or information will set them up for failure. When team members do not have what it takes to complete the work, effective project leaders rectify this situation very clearly by finding ways to transfer the knowledge or reassign the work. The rhythm and flow of a high-performing team can be irreparably damaged by project leaders who fail to act in these situations.

High-Performing Teams

Effective project leaders create high-performing teams. According to Katzenbach and Smith in their Harvard Business Review (HBR) article “The Discipline of Teams,” the five elements that make teams function are:14

- Common commitment and purpose

- Specific performance goals

- Complementary skills

- Commitment to how the work gets done

- Mutual accountability

Further, according to Katzenbach and Smith, who have observed successful teams in action, there are a number of practices that make teams truly effective. These practices include:

- Establishing urgency

- Demanding performance standards

- Providing direction

Teams work best when they have a compelling reason for being, and it is thus more likely that the teams will be successful and live up to demanding performance expectations. When teams are brought together to address an “important initiative” for an organization, they require clear direction and a truly compelling reason to prevent them from losing momentum and withering. Let us examine some of the methods used to create high-performing teams.

Teams have a much better chance of being high-performing when members are selected based on their skills and ability to collaborate with others. This is not always as easy as it sounds for several reasons. Firstly, most individuals would prefer to have people they like on their team, especially when they have fun, positive personalities. This will translate into an enjoyable work environment. However, it can turn into a frustrating environment if those individuals do not have the required skillset (or the potential to acquire knowledge) to contribute towards the project’s deliverables. It is important that the project leader spends time thinking about the purpose of the project and the anticipated deliverables. This will allow the project leader to identify the specific skills needed on the team.

Once the team is assembled, it is important to pay particular attention to the first meetings and actions. Project teams will interact with many different people, such as functional subject-matter experts and senior leadership, which is why the team must look and be perceived as competent. Further, project leaders who pay attention to their team’s emotional intelligence and find ways to enhance it are much more likely to successfully navigate stakeholder expectations.

Project leaders that take the time to find early quick wins for their team will prepare them for the more challenging tasks and goals that will occur later in the project. These quick wins build team rapport by fostering feelings of team accomplishment and cohesion.

Introducing change into an organization is challenging. It is important to be continuously researching and questioning the assumptions the team is making about the project. Sometimes the team’s expectations are proven to be unfeasible aspirations, and, if detected too late, can lead to poorly designed solutions or even project failure. Project leaders can encourage their teams to identify and challenge their own assumptions by teaching them how to scan for new information in the environment. Staying curious and inquisitive are mindsets that can be modelled by the project leader. Teams that take on these mindsets are much more likely to be able to keep up with global change and understand how this change affects their project.

It is also important to spend time together. Teams are so busy that they can overlook the importance of bonding. Time in person, on the phone, in meetings—all of it counts and helps to build camaraderie and trust. In turn, this leads to better collaboration among team members. Many project leaders assume people are naturally good collaborators, but this is often not the case. However, relationship-building skills and effective collaboration techniques can be taught. Project leaders who provide training for their teams in this area are more likely to create a high-performance team. Furthermore, as team members demonstrate effective collaboration skills, it is important that project leaders share positive feedback, provide recognition, and link the team’s performance to rewards. These are key performance management tools that build high-performing teams by reinforcing desired behaviours.

Formal performance review processes are critical to project success. Although some of the project team members will return to their functional teams upon project closure, project leaders are accountable for individual performance during the life of the project. Performance reviews are important to keep projects on track and they represent an investment in the continued development of an organization’s human resources. Project leaders should consider how they will evaluate individual performance and share this with the team in order to ensure transparency in expectations. Performance is a function of what is delivered and how it is delivered. High-performing teams consider both, not just the results. This is because team members who produce the best results but cause negativity in their team environment can prevent the entire team from reaching its full potential.

Team Development

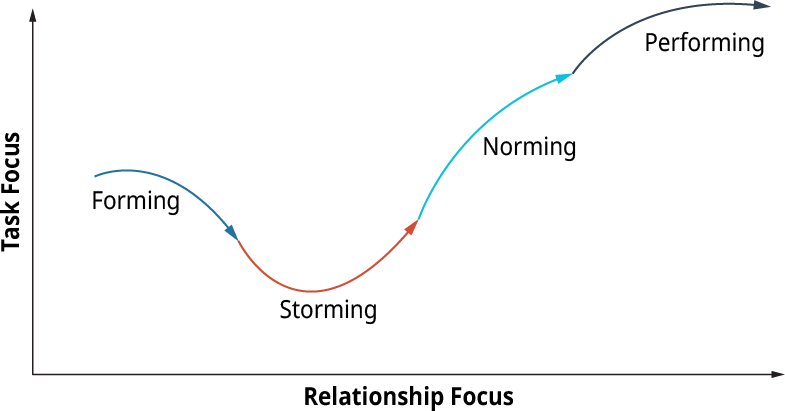

Most of us have been part of a team. Reflecting on our experiences, we can recall what it felt like when the team first came together, when challenges emerged, and when it was time to part ways. All teams have different “stages” of team development. Team members often start from a position of friendliness and excitement about a project, but the mood can sour, causing the team dynamics to worsen very quickly once the real work begins. In 1965, educational psychologist Bruce Tuckman at Ohio State University developed a four-stage model to explain the complexities that he had witnessed in team development. The original model was called Tuckman’s Stages of Group Development and he worked with Mary Ann Jensen to add the fifth stage of “Adjourning” in 1977 to explain the disbanding of a team at the end of a project15. The five stages of the Tuckman model are:

- Forming

- Begins with the introduction of team members

- Known as the “polite stage” in which the team is mainly focused on similarities and the group looks to the leader for structure and direction

- Team members at this point are enthusiastic, and issues are still being discussed on a global, ambiguous level

- Informal leadership order begins to develop, but the team is still friendly

- Storming

- Begins as team members begin vying for leadership and testing the group processes

- Known as the “win-lose” stage, as members clash for control of the group and people begin to choose sides

- A period of high conflict

- The attitude about the team and the project begins to shift to negative, and there is frustration around goals, tasks, and progress

- Can be a very long and painful process

- Norming

- The team is slowly starting to work well together, and buy-in to group goals occurs

- They begin establishing and maintaining ground rules and boundaries, and there is a willingness to share responsibility and control

- At this point in the team formation, members begin to value and respect each other and their contributions

- Performing

- The team builds momentum and starts to get results

- The team is self-directed and requires little management direction

- The team has confidence, pride, and enthusiasm, and there is a congruence of vision, team, and self

- As the team continues to perform, it may succeed in becoming a high-performing team.

- High-performing teams have optimized both task and people relationships—they are maximizing performance and team effectiveness

- Adjourning

- The goal or project has been completed

- If the team was successful, this can be a time of celebration. If the team was not successful, the failures can make it difficult for individual members to move on to their next assignment as they process what led to the failures and take stock of what they’ve learned on an individual level

- Can be difficult as team members have to let go of the solutions they’ve developed and potentially the relationships they have enjoyed building

Exhibit 6.2: Tuckman’s Model of Team Development

Rice University, OpenStax

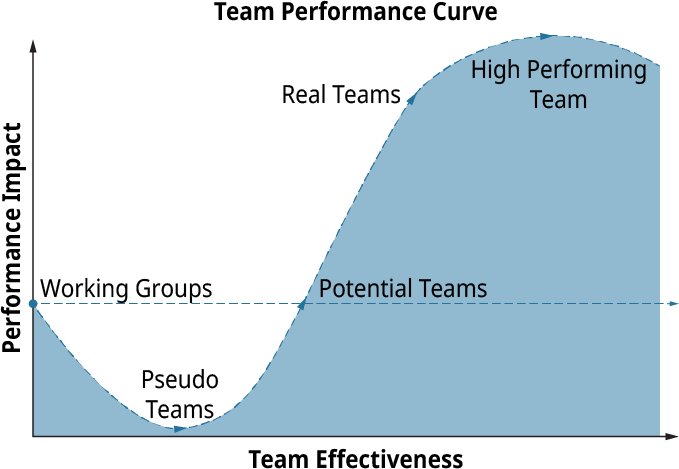

Katzenberg and Smith, in their study of teams, have created a “team performance curve,” graphing the journey of a team from a working group to a high-performing team. The team performance curve is illustrated below.

Exhibit 6.3: Team Performance Curve

Rice University, OpenStax

In addition to Katzenbach and Smith’s five characteristics of high performing teams identified above, let’s explore how these authors define each stage of the team performance curve.

Working Groups lack a common purpose or goal that calls for a team approach or mutual responsibility. The members of a working group interact primarily to share or obtain information, share “best practices” and perspectives and to make decisions that helps each member of the group perform within their own role.

Pseudo Teams have no interest in developing a common purpose or establishing common performance goals, despite the fact that they may call themselves a “team”. The interactions detract from each member’s individual performance and as result, the sum of the whole is less than the potential of the individual performances (1+1+1+1=3). Pseudo teams are the weakest of all groups in terms of performance.

Potential Teams do have an interest in collectively improving their performance by establishing a common purpose and mutual accountability. In order to progress, they need to continue working on clarifying their purpose, goals and common approach. This is done by building a common working approach.

Real Teams are made up of people with complementary skills who are equally committed to a common purpose, goals and a working approach. They are also able to hold themselves mutually accountable. Their collective performance is much higher than those of working groups and potential teams (1+1+1+1=5).

High Performing Teams have a common commitment and purpose, specific performance goals, complementary skills, commitment to how the work gets done and mutual accountability. Uniquely, they are also deeply committed to one another’s personal growth and success.

Evolving into a high-performance team is not a linear process. Similarly, the stages of team development in the Tuckman model are also nonlinear, and there are even factors that may cause the team to regress to an earlier stage of development. When a team member is added to the group, this may cause enough disruption in the dynamic that the team does a backwards slide into an earlier stage of development. Similarly, a backwards slide can occur if a new project task is introduced and it causes confusion or anxiety for the group. These events can cause the team to have to re-form, re-storm and re-norm before getting back to the performing stage as a team. Project leaders who understand the natural stages of team development are much more likely to mentor their teams into becoming high-performing. Leadership is not a spectator sport. Project leaders cannot stand by and watch their teams flounder as they struggle through the unique challenges of each stage. Project leaders should be regularly assessing which stage their teams are in and proactively assisting them to move through each stage on their journey to becoming high-performing.

Creating a Project Culture

Project leaders have a unique opportunity to create a project culture during its start-up, which is something organizational managers seldom have a chance to do. As discussed in Chapter 3, in most organizations, the corporate or organizational culture has developed over the life of the organization, and people associated with the organization understand what is valued, what has status, and what behaviours are expected.

Characteristics of Project Culture

A project culture encompasses the shared norms, beliefs, values, and assumptions of the project team. Understanding the unique aspects of a project culture and developing an appropriate culture to match the complexity profile of the project are important project management abilities.

Culture is developed through the communication of:

- The priority

- The given status

- The alignment of official and operational rules

Official rules are the rules that are stated, and operational rules are the rules that are enforced. Project leaders who set official and operational rules are more effective in developing a clear and strong project culture because the project rules are among the first aspects of the project culture to which team members are exposed when assigned to the project.

Culture guides behaviour, communicates what is important, and is useful for establishing priorities. On projects with a strong culture of trust, team members will not hesitate to challenge anyone who betrays confidence, even managers. In this example, the project’s culture of integrity is stronger than the organization’s culture of power and authority.

Team Diversity

Decision-making and problem-solving can be much more dynamic and successful when they materialize in a diverse team environment. The diversity in perspectives can enhance both the understanding of the problem and the quality of the solution. Diversity is a word that is very commonly used today, but the importance of diversity and building diverse teams can sometimes wane in the normal processes of doing business.

David Rock and Heidi Grant’s research in the Harvard Business Review article Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter has shown that diverse teams are better at decision-making and problem-solving because they tend to focus more on facts.16 A study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology exhibited that people from diverse backgrounds “might actually alter the behaviour of a group’s social majority in ways that lead to improved and more accurate group thinking.” (see Footnote 16). The study concluded that the diverse committees raised more facts related to the case than homogenous committees and made fewer factual errors while discussing available evidence. The article noted another research paper demonstrating that diverse teams are “more likely to constantly re-examine facts and remain objective. They may also encourage greater scrutiny of each member’s actions, keeping their joint cognitive resources sharp and vigilant. By breaking up workforce homogeneity, employees become more aware of their own potential biases, which are entrenched ways of thinking that can otherwise blind them to key information and even lead them to make errors in decision-making processes.” (see Footnote 16)

When people are among homogeneous and like-minded (nondiverse) teammates, the team is susceptible to groupthink and may be reticent to think about opposing viewpoints since all team members are in alignment. In a more diverse team with a variety of backgrounds and experiences, the opposing viewpoints are more likely to come out and the team members feel obligated to research and address the questions that have been raised. Again, this enables a richer discussion and a more in-depth fact-finding and exploration of opposing ideas and viewpoints in order to solve problems.

Project leaders need to reflect upon these findings during the early stages of team selection so that they can reap the benefits of having diverse voices and backgrounds.

Multicultural Teams

As globalization has increased over the last decades, workplaces have felt the impact of working within multicultural teams. The earlier section on team diversity outlined some of the highlights and benefits of working on diverse teams, and a multicultural group certainly qualifies as diverse. However, there are some key recommended practices for those who are leading multicultural teams to highlight the advantage of diversity rather than viewing it as an obstacle.

People may assume that communication is the key factor that can cause derailment of a multicultural team, citing different languages and communication styles among members as the problems. However, in the Harvard Business Review article Managing Multicultural Teams, Jeanne Brett, Kristin Behfar, and Mary Kern point out four key cultural differences that can cause destructive conflicts in a multicultural team.17

- The first cultural difference is direct versus indirect communication. Some cultures are very direct and explicit in their communication, while others are more indirect and ask questions rather than pointing out problems.

- May cause conflict because, at the extreme, the direct style may be considered offensive by some, while the indirect style may be perceived as unproductive and passive-aggressive in team interactions.

- The second cultural difference is trouble with accents and fluency. When team members do not speak the same language, there may be one language that dominates the group interaction, causing team members who are not as fluent to feel excluded.

- May cause conflict due to the withdrawal of non-fluent speakers, leading the speakers of the primary language to feel that non-fluent team members are not as valuable to the team or are less competent.

- The third cultural difference is the presence of differing attitudes toward hierarchy. Some cultures are very respectful of the hierarchy and will treat team members based on where they fall within that hierarchy. Other cultures are more egalitarian and do not observe hierarchical differences to the same degree.

- May cause conflict if some people feel that they are being disrespected and not treated according to their status.

- The fourth cultural difference is conflicting decision-making norms. Different cultures make decisions differently, and some will apply a great deal of analysis and preparation beforehand.

- May cause conflict because the cultures that make decisions more quickly (and need just enough information to make a decision) may be frustrated with the slow response and relatively longer thought process.

These cultural differences are good examples of how everyday team activities (decision-making, communication, interaction among team members) may become points of contention for a multicultural team if there is not an adequate understanding of everyone’s culture.

In their article, Brett, Behfar, and Kern propose that there are several potential interventions to try if these conflicts arise.

- Adaptation is working with or around differences. This technique is best used when team members are willing to acknowledge the cultural differences and learn how to work with them.

- Structural intervention is the reorganization of the team’s composition in an attempt to reduce friction. This technique is best used if there are unproductive subgroups or cliques within the team that need to be moved around.

- Managerial intervention is allocating decision-making to management, thereby removing the team’s involvement. This technique is one that should be used sparingly, as it implies to the team that they need guidance and cannot move forward without management getting involved, which can reduce their morale and lead to further issues.

- Exit is the voluntary or involuntary removal of a team member and should only be used as a last resort. If the differences and challenges have proven to be so great that an individual on the team can no longer work productively with the team, it may be necessary to remove the team member in question.

There are some people who seem to be innately aware of and able to work with cultural differences on teams and in their organizations. These individuals might be said to have cultural intelligence. Cultural intelligence is a competency and a skill that enables individuals to function effectively in cross-cultural environments. It develops as people become more aware of the influence of culture and more capable of adapting their behaviour to the norms of other cultures. In the IESE Insight article Cultural Competence: Why It Matters and How You Can Acquire It, the authors, Yih-teen Lee and Yuan Liao, assert that multicultural leaders may relate better to team members from different cultures and resolve conflicts more easily.18

As a project leader of a multicultural team, there are a few best practices that the authors recommend for honing cross-cultural skills.

The first is to broaden your mind—expand your own cultural channels (travel, movies, books) and surround yourself with people from other cultures. This helps to raise your own awareness of the cultural differences and norms that you may encounter.

Another best practice is to develop your cross-cultural skills through practice and experiential learning. You may have the opportunity to work or travel abroad, but if you do not, then familiarizing yourself with the company’s cross-cultural members or foreign visitors will help you to practice your skills.

Virtual Project Teams

Virtual project teams are comprised of people that are not co-located in the same physical environment. All the work produced by the team is done through the use of information technology that facilities virtual collaboration. There are many advantages and disadvantages of virtual project teams. Some of the key advantages and disadvantages are listed below:

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Cost savings | Social isolation of team members who work virtually |

| Greater access to a diverse labour force not encumbered by 8-hour workdays | Potential for lack of trust among team members and the organization when communication is limited |

| Decreased response time to customers | Reduced collaboration among separated team members due to lack of social interaction |

| Less harmful effects on the environment |

The advantages create compelling benefits that are easy to accept. However, the disadvantages require very intentional planning and frequent team-building activities to overcome. During project initiation, when the infrastructure of the project is being developed, the project team should identify their collaboration requirements and select information technology that will be adequate in fulfilling their needs. The technology must be widely accepted and easy to use. Training should be provided to all members of the project team, including stakeholders who are not involved in the day-to-day activities associated with producing the deliverables. Training can help overcome individual resistance to new technology. Lastly, it is very easy for team members to “disappear” in the vastness of virtual communication. Successful project leaders leading virtual teams regularly schedule short but impactful team connection sessions that help the team build trust and overcome feelings of isolation.

Working with Individuals

Project leaders that have been successful in creating a high-performing team not only have the skills needed to lead groups of people, they are also effective in working intimately with individuals. Working with individuals involves dealing with them both tactically (task-oriented) and emotionally. A successful working relationship between individuals begins with appreciating the importance of emotions and how they relate to personality types, leadership styles, negotiations, and setting goals.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotions are both a mental and physiological response to environmental and internal stimuli. Leaders must understand and value their emotions to appropriately respond to the Project Sponsor, project team, and project environment.

Emotional intelligence includes the following:

- Self-awareness

- Self-regulation

- Empathy

- Relationship management

Emotions are important in generating energy around a concept, building commitment to goals, and developing high-performing teams. Emotional intelligence is an important part of the project leader’s ability to build trust, and establish credibility or open dialogue with project stakeholders. Emotional intelligence is critical for project leaders, which is why the more complex the project profile, the more important the project leader’s emotional intelligence becomes to project success.

Personality Types

Personality types refer to the differences among people in such matters as motivation, information processing (for example, how experiences influence the way people perceive the environment and how people develop filters that allow certain information to be retained while other information is excluded), conflict styles, and so forth. Understanding the differences among people is a critical leadership skill. Understanding your personality type as a Project leader will assist you in evaluating your tendencies and strengths in different situations.

There are many personality-type tests that have been developed to explore different aspects of people’s personalities. Some project leaders use these tests as a team-building tool during project start-up. This is typically a facilitated work session where team members take personality inventories, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, and share with the team how they process information, their preferred communication approaches, and the decision-making style they possess. This allows the team to identify potential areas of conflict, develop communication strategies, and build an appreciation for the diversity of the team before the difficult work begins. Two commonly used personality assessment tools will be explored below.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is one of the most widely used tools for exploring personal preference. It is often referred to as simply the Myers-Briggs. Based on the theories of psychologist Carl Jung, the MBTI uses a questionnaire to gather information on the ways individuals prefer to use their perception and judgment. Perception represents the way people become aware of people and their environment. Judgment represents the evaluation of what is perceived. People perceive things differently and reach different conclusions based on the same environmental input. Understanding and considering these differences is critical to successful project leadership.

The MBTI identifies 16 personality types based on four continuums. The preferences are between pairs of opposite characteristics and include the following dichotomies:

- Extroversion (E) — Introversion (I)

- Describes a preference for focusing on the outer (E) or inner (I) world

- Sensing (S) — Intuition (N)

- Describes a preference for approaching and internalizing information

- Thinking (T) — Feeling (F)

- Describes a preference for decision making

- Judging (J) — Perceiving (P)

- Describes a preference for planning

For example, an ISTJ is a Myers-Briggs type who prefers to focus on the inner world, prefers logic, and likes to decide quickly. It is important to note that there is no “best” type and that effective interpretation of the Myers-Briggs requires training. The purpose of the Myers-Briggs is to understand and appreciate the differences among people. It is important to note, however, that people do not neatly fall into these dichotomies. Many Myers-Briggs tests provide percentages for the traits; for example, someone who is an ISTJ may receive 99% on introversion and 1% on extroversion, while another receives 51% on introversion and 49% on extroversion.

Another theory of personality typing is the DISC method, which rates people’s personalities by testing a person’s preferences in word associations in the following four areas:

- Dominance/Drive —relates to control, power, and assertiveness

- Inducement/Influence —relates to social situations and communication

- Submission/Steadiness —relates to patience, persistence, and thoughtfulness

- Compliance/Conscientiousness —relates to structure and organization

Remember: personality traits reflect an individual’s preferences, not their limitations. It is important to understand that individuals can still function in situations for which they are not best suited according to their personality assessment results. It is also important to realize that you can change your leadership style according to the needs of your team and the particular project’s attributes and scope.

For example, a project leader who is more “thinking” than “feeling” in MBTI would need to work harder to be considerate of how team members who are more “feeling” may react if they were singled out in a meeting because they were behind schedule.

In evaluating these tools, there a number of important considerations. The first is how willing the project team is to participate. Does the project team see value in understanding the personality types of their colleagues? Are they willing to share information about themselves? How long does the assessment take to complete? Before purchasing one of the available tools, project leaders should discuss the benefits of using this approach with their team and then select the tool that is most beneficial for the team.

Motivation

Understanding what motivates people is another critical leadership skill. In the early 1900s, Fredrick Winslow Taylor was a mechanical engineer widely known for his methods of improving worker productivity. He became one of the first management consultants and his views were based on an underlying theory that work consists mainly of simple, not particularly interesting, tasks. The only way to get people to do them is to incentivize them properly and monitor them carefully.19

His management philosophy became known as Taylorism. His philosophy may have been appropriate in the early 1900s, but the nature of work is fundamentally different in the 21st century. Thankfully, mechanical engineers have found ways to automate many mundane physical tasks while information technology frees us from manually “crunching” tons of data. Work is now much more interesting and challenging.

In Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Daniel Pink argues that rewards based on an “if/then” approach (if you do this, then you get that) can produce the opposite outcome of what we are striving for.20 If/then thinking is also referred to as a “carrot-and-stick” philosophy where carrots are incentives and sticks are punishments. Pink suggests that the reason why this approach does not work is because rewards, by their very nature, narrow our focus. (see Footnote 20). He concludes that simple monetary rewards can be helpful if there is a “clear path to a solution” as they help us “race ahead and race faster”. However, many of today’s challenges lack clear definitions and certainly lack clear simple solutions.

In order for project leaders to effectively motivate people into successfully introducing organizational change initiatives, they must let go of the use of authority, money, and penalties (extrinsic motivation), replacing them with autonomy, mastery, and purpose (intrinsic motivation). The purpose behind this shift in motivation is about helping people discover the inherent satisfaction associated with the activity itself versus external rewards that can only fuel short-term performance at best.

Autonomy is about trusting individuals to be self-directed. From a project perspective, asking individuals to help identify and shape the way work will be done is much more likely to lead to project success. Telling people what to do, when to do it, and how to do it will crush their creativity and can diminish their performance. Giving people autonomy will significantly improve their motivation.

Mastery is about becoming better at something that matters. Since mastery is impossible to fully realize, it can be frustrating and alluring at the same time. Ask any professional and they will easily be able to share the next big “thing” they are trying to master. Think about this in the context of a hobby or sporting activity. Speak with an avid golfer and they are likely to tell you that landing a 20-foot putt or a 400-yard drive is enough to keep them coming back the next day, despite missing three easy putts in previous holes. From a project perspective, it is important for project leaders to be aware of the skills their team members are working towards mastering. Finding ways to allow them to work on their mastery in this area is another great way to improve their motivation.

Purpose involves identifying the value of the “cause” people are working toward. It puts the “why” back into our day-to-day lives. As Daniel Pink succinctly stated in his book, “humans, by their nature, seek purpose.” Purpose is about contributing and being part of a cause greater than ourselves. More and more people are no longer motivated by profit maximization. Purpose maximization has become extremely important. In the context of project management, project leaders must ensure that their teams have a clear understanding of the value and impact of their project on the organization’s success, on customers, and on the employee experience.

6.2 Scope Validation

The objective of validating scope is to ensure that the project team is meeting stakeholder expectations. This occurs when the project sponsor (and appropriate designates) formally accepts a deliverable. Obtaining acceptance (sign-off) can be challenging because it must happen at the deliverable level and at the project objective level. As outlined in Section 5.2, the approach taken to plan a project’s scope depends on the development methodology being used.

If the solution can be well-defined upfront, the predictive/waterfall development methodology would be used and a detailed scope statement can be produced to guide the development efforts of the whole project. In contrast, some project teams know that the end solution is unclear and, therefore, the scope is unclear. Project teams would use an adaptive development approach in these situations. The end solution, and hence the scope, is defined in an iterative or incremental fashion. By definition, scope is very fluid.

Aside from the unique timing differences of when the scope is determined and validated, both development methodologies require the project team to confirm stakeholder expectations are being met. This occurs by reviewing the deliverables produced by the project with the project sponsor (and appropriate designates). These reviews may be held through live demonstrations of what has been built, depending on the nature of the project. Before the formal deliverable review occurs, project teams will have assessed the quality of the work performed to confirm it is ready for stakeholder review.

As each deliverable is reviewed, it is also important for the project leader to confirm the project team has the necessary resources and time to develop the remaining work that is expected in the future. Further, it is possible that deliverable reviews will result in the identification of new requirements. When this occurs, this is considered a “change request” if the predictive/waterfall approach was used. In adaptive development methodologies, such as agile, new requirements are expected.

6.3 Dealing with Change

Change is a common occurrence on projects. Since projects require the integration of many different components, such as human resources, communication, and vendor management, change in one of these components often has a ripple effect throughout the entire project. Effective change management addresses the full effect of change and allows the project leader to understand the impact of change on the project’s objectives.

Duration and cost estimates can frequently change. Despite best efforts to estimate as accurately as possible, things can and do go wrong. Resource shortages are difficult to anticipate but are common. In addition, collaboration time (time for input/discussion) can be very challenging to estimate because stakeholders are often busy people with conflicting schedules. When this collaboration time finally occurs, it may be much later than the project team hoped for and this would be largely out of their control. As such, it is important to update original estimates to reflect the new reality.

Project leaders must be constantly examining for what has changed or what should change in order to successfully achieve the project’s objectives. When the need for change is discovered, it is important that its full impact is assessed and the appropriate team communication occurs as quickly as possible. In addition, the project team must understand the priorities and trade-offs in a project. These priorities will impact how and when change is introduced. For instance, on projects where the timeline is the most important constraint, project teams will attempt to protect the schedule by making trade-offs with the budget, scope, and/or quality. An impact assessment is done before actions are taken. The assessment would lead to recommendations which are then provided to the project sponsor (and appropriate designates) in order for decisions to be made with stakeholder involvement.

It is important to note that the development methodology used also has a big impact on how change is introduced. Change is more difficult to manage when predictive/waterfall methodologies are used because it is often not expected or considered when commitments have already been made. Change is expected when an adaptive approach was selected for the project.

When the predictive/waterfall development methodology is used, it is critical for the project team to discuss change management processes with the project sponsor during the planning phase. High-complexity projects will often document these decisions in a project management plan. Plans of this nature facilitate decision-making with project sponsors around thresholds, approval requirements, and communication preferences. If the change will alter the project’s duration, budget, scope, and/or quality, most project sponsors will want to ensure their approval to proceed is obtained before the change is made.. This approach is largely unnecessary when an adaptive methodology is being used. This is because the product owner is involved in the planning of every iteration. In fact, the product owner decides the scope of each iteration while trying to maximize organizational value and adhering to scheduling and budget constraints.

When the predictive/waterfall) development methodology is used, the change process is initiated with a change request. This is a document that identifies what the change is about, its impact on the project, the organizational value, and what would be required to implement it. Not all changes are approved as they may not provide enough organizational value, be affordable, and/or be feasible from a scheduling perspective. If the change is approved, it is sent back to the project team for implementation.

References

1 Yukl, A. (1981). Leadership in organizations. Prentice-Hall.

2 Kellerman, B. (1984). Leadership: Multidisciplinary perspectives. Prentice-Hall; Landy, F. L. (1985). Psychology of work behavior. Dorsey Press.

3 Burns, M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row; Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

4 Daft, L. (2018). The Leadership Experience (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

5 Baum, R., Locke, E. A., & Kirkpatrick, S. A. (1998). A longitudinal study of the relation of vision and vision communication to venture growth in entrepreneurial firms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 43-54.

6 Bennis, W. (1989). On becoming a leader. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.

7 Judge, A., & Bono, J. E. (2000). Five-factor model of personality and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 751-765.

8 Pillai, R., Schriesheim, C. A., & Williams, E. S. (1999). Fairness perceptions and trust as mediators for transformational and transactional leadership: A two-sample study. Journal of Management, 25, 897-933.

9 Manz, C., & Sims, H. P. Jr. (1987). Leading workers to lead themselves: The external leadership of self-managed work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32,106-129.

10 De Smet, A., Lurie, M., & St George, A. (2018, October). Leading agile transformation: The new capabilities leaders need to build 21st-century organizations. McKinsey & Company.

11 Lencioni, P. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team (p. 188). Jossey-Bass.

12 Larson, E. W., & Gray, C. (2021). Project management: The managerial process (8th ed.). McGraw Hill Education.

13 Inam, H. (2018). Managing team conflict. LinkedIn Learning. https://www.linkedin.com/learning/managing-team-conflict/welcome?u=2169170

14 Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (2005). The discipline of teams. Harvard Business Review.

15 Scholtes, P. R., Joiner, B. L., & Streibel, B. J. (2018). The team handbook (3rd ed.). GOAL/QPC.

16 Rock, D., & Grant, H. (2016, November). Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review.

17 Brett, J., Behfar, K., & Kern, M. (2007). Managing multicultural teams. Harvard Business Review.

18 Lee, Y., & Liao, Y. (2015). Cultural competence: Why it matters and how you can acquire it. IESE Insight.

19 Kanigel, R. (2005). The one best way: Fredrick Winslow Taylor and the enigma of efficiency. MIT Press.

20 Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us (pp. 22-57). Riverhead Books.