Chapter 3: Understanding People at Work, Individual Differences and Perception

Chapter Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to know and learn the following:

- Define personality and describe how it affects work behaviours.

- Understand the role of values in determining work behaviours.

- Explain the process of perception and how it affects work behaviours.

- Understand how individual differences affect ethics.

- Understand cross-cultural influences on individual differences and perception.

Introduction

Most executives assume they know who their “people” people are: They’re the team players, the ones who know what’s going on in their colleagues’ personal lives, the ones who can smooth over interpersonal conflicts. They’re usually found in human resources or sales. The truth, however, is much more nuanced than that. Interpersonal savvy is critical in almost every area of business, not just sales and HR. In fact, it comprises aptitudes( skills) and attitides that are more varied than a lot of people might think. we know that individuals do their best work when it most closely matches their underlying interests. Managers, therefore, can boost productivity by using their employees’ relational interests and skills to guide personnel choices, project assignments, and career development.

Alicia DiGiavonni is the internal medicine unit manager at a Boston-area HMO. Alicia has an MBA and is a focused, task-oriented operating manager, but her success comes from her effectiveness as the organization’s unofficial psychologist. Alicia has done more in the way of counseling, conflict resolution, coaching, and informal personality assessment than many of the therapists who work in the mental health unit. Staff members frequently confide in her when there is disabling friction within a work team, when they need career advice, or when they’re struggling with personal issues. She is an expert at recognizing hidden agendas at meetings and identifying the problems that workers are reluctant to share with senior managers. She knows which combinations of people on a project team would yield great synergy and which would be disastrous. On countless occasions, Alicia has kept projects on track through skillful, behind-the-scenes interventions.

Diane Weiss, a senior editor for a major magazine. Whether the question is which illustration to use, how best to express data graphically, what title to give an article, or what image to put on the cover, Diane is the one to ask: She has an unerring sense of what will pull readers in. But she is not known for her easy management style or her ability to “read” people. In fact, even her most ardent fans will agree that she can be exceedingly difficult to work with. For understanding the masses, though, Diane is as good as you can get. She is a genuine people person.

Andy Keller, manages sales for the West Coast region of a successful sporting goods company. Likable and full of energy, Andy was one of a handful of MBA graduates from an esteemed business school who pursued a career in sales. His classmates saw sales as a low-prestige option, but Andy knew what he wanted. Almost immediately, he became a top-performing rep. He enjoyed driving from pro shop to pro shop, talking both with the store managers and with the players coming off the golf course. But while he liked selling, when he was promoted to manage a sales team in northern California, he loved it—which is not always the case when salespeople move into management. Andy would be the first to tell you that he is neither a strategist nor a negotiator. He’s more interested in talking to people and leading a team; he also likes seeing tangible feedback on his—and his group’s—performance every month.

Individuals bring a number of differences to work, such as unique personalities, values, emotions, and moods. When new employees enter organizations, their stable or transient characteristics affect how they behave and perform. Moreover, companies hire people with the expectation that those individuals have certain skills, abilities, personalities, and values. Therefore, it is important to understand individual characteristics that matter for employee behaviours at work.

3.1 Advice for Hiring Successful Employees: The Case of Guy Kawasaki

When people think about entrepreneurship, they often think of Guy Kawasaki , who is a Silicon Valley venture capitalist and the author of nine books as of 2010, including The Art of the Start and The Macintosh Way. Beyond being a best-selling author, he has been successful in a variety of areas, including earning degrees from Stanford University and UCLA; being an integral part of Apple’s first computer; writing columns for Forbes and Entrepreneur Magazine; and taking on entrepreneurial ventures such as cofounding Alltop, an aggregate news site, and becoming Managing Director of Garage Technology Ventures. Kawasaki is a believer in the power of individual differences. He believes that successful companies include people from many walks of life, with different backgrounds and with different strengths and different weaknesses. Establishing an effective team requires a certain amount of self-monitoring on the part of the manager. Kawasaki maintains that most individuals have personalities that can easily get in the way of this objective. He explains, “The most important thing is to hire people who complement you and are better than you in specific areas. Good people hire people that are better than themselves.” He also believes that mediocre employees hire less–talented employees in order to feel better about themselves. Finally, he believes that the role of a leader is to produce more leaders, not to produce followers, and to be able to achieve this, a leader should compensate for their weaknesses by hiring individuals who compensate for their shortcomings.

In today’s competitive business environment, individuals want to think of themselves as indispensable to the success of an organization. An individual’s perception that he or she is the most important person on a team can get in the way of the team’s success. Kawasaki maintains that many people would rather see a company fail than thrive without them. He advises that we must begin to move past this and see the benefit that different perceptions and values can bring to a company. The goal of any individual should be to make the organization they work for stronger and more dynamic. Under this type of thinking, leaving a company in a better shape than when you found it becomes a source of pride. Kawasaki has had many different roles in his professional career and as a result realized that while different perceptions and attitudes might make the implementation of new protocol difficult, this same diversity is what makes an organization more valuable. Some managers fear diversity and the possible complexities that it brings, and they make the mistake of hiring similar individuals without any sort of differences. When it comes to hiring, Kawasaki believes that the initial round of interviews for new hires should be held over the phone. Because first impressions are so important, this ensures that external influences, negative or positive, are not part of the decision-making process.

Many people come out of business school believing that if they have a solid financial understanding, then they will be a successful and appropriate leader and manager. Kawasaki has learned that mathematics and finance are the “easy” part of any job. He observes that the true challenge comes in trying to effectively manage people. With the benefit of hindsight, Kawasaki regrets the choices he made in college, saying, “I should have taken organizational behaviour and social psychology” to be better prepared for the individual nuances of people. He also believes that working hard is a key to success and that individuals who learn how to learn are the most effective over time.

If nothing else, Guy Kawasaki provides simple words of wisdom to remember when starting off on a new career path: do not become blindsided by your mistakes, but rather take them as a lesson of what not to do. And most important, pursue joy and challenge your personal assumptions (Kawasaki, 2004; Iwata 2008).

3.2 The Role of Fit

Have you heard of Red Bull? Tried it? Enjoyed the taste and the feeling? Or maybe not.

Red Bull has a very unique way of hiring talent that they beleive will be a good fit to the organisation.

Red Bull use their trademark slogan to fit within their recruitment process by stating “Red Bull Wingfinder, give wings to your career.”

The test takes about 30 minutes and is based on 30 years of psychological research.

The genius behind this recruitment technique is that often candidates want a role in a company where they can develop and progress within their career.

Red Bull is paving the way for employee learning and progression making them attractive prospective employers.

Individual differences matter in the workplace. Human beings bring in their personality, physical and mental abilities, and other stable traits to work. Imagine that you are interviewing an employee who is proactive, creative, and willing to take risks. Would this person be a good job candidate? What behaviours would you expect this person to demonstrate?

The question posed above is misleading. While human beings bring their traits to work, every organization is different, and every job within the organization is also different. According to the interactionist perspective, behaviour is a function of the person and the situation interacting with each other. Think about it. Would a shy person speak up in class? While a shy person may not feel like speaking, if the individual is very interested in the subject, knows the answers to the questions, and feels comfortable within the classroom environment, and if the instructor encourages participation and participation is 30% of the course grade, regardless of the level of shyness, the person may feel inclined to participate. Similarly, the behaviour you may expect from someone who is proactive, creative, and willing to take risks will depend on the situation.

When hiring employees, companies are interested in assessing at least two types of fit. Person–organization fit refers to the degree to which a person’s values, personality, goals, and other characteristics match those of the organization. Person–job fit is the degree to which a person’s skill, knowledge, abilities, and other characteristics match the job demands. Thus, someone who is proactive and creative may be a great fit for a company in the high-tech sector that would benefit from risk-taking individuals but may be a poor fit for a company that rewards routine and predictable behaviour, such as accountants. Similarly, this person may be a great fit for a job such as a scientist, but a poor fit for a routine office job. The opening case illustrates one method of assessing person–organization and person–job fit in job applicants.

3.3 Individual Differences: Values and Personality

Values

Values refer to stable life goals that people have, reflecting what is most important to them. Values are established throughout one’s life as a result of the accumulating life experiences and tend to be relatively stable (Lusk & Oliver, 1974; Rokeach, 1973). The values that are important to people tend to affect the types of decisions they make, how they perceive their environment, and their actual behaviours. Moreover, people are more likely to accept job offers when the company possesses the values people care about (Judge & Bretz, 1992; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). Value attainment is one reason why people stay in a company, and when an organization does not help them attain their values, they are more likely to decide to leave if they are dissatisfied with the job itself (George & Jones, 1996).

You are working for a profitable company that excels in its industry. But something is not right. Why is it you don’t feel engaged and excited about your job? Instead of excelling and loving your job, it is just a “job” and you continue to work for the company only because of the money. What would it be like if you went to work each day and not only got the salary you deserve but you loved the job you were doing?

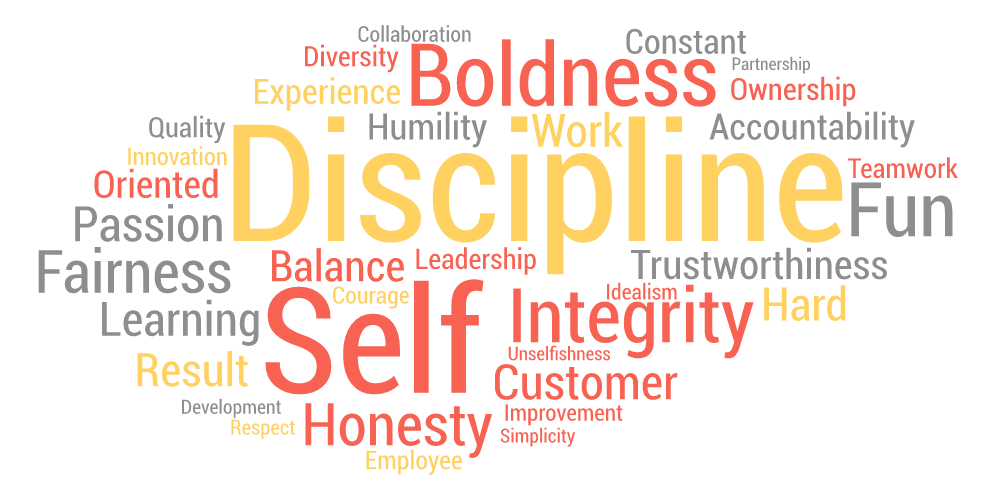

Research has shown that when you match your personal values to the values of the Company there is synergy. Employees are happier and more engaged. The values of a Company underlie the purpose and drive to move forward. The values are the “Why” that make a difference. They lead to impact and performance for employees.

When business objectives become a personal matter, a closer connection is made. Employees feel they are part of the bigger picture and have a reason to work hard and produce. Remember, both internally to their teammates and to the public.

So what values in a company make a difference for you? Is it strictly skill driven and hard work? Or is it the right mix of both skills and developing and recognizing your people?

Ask yourself. What values does your Company embrace? Is it Collaboration, Trust and Communication? Or is it Innovation, Drive and Intelligence? What if your company had the right mix all six elements?

When there is Trust, employees feel safe. You understand the purpose and have a greater drive to see the company succeed.

With Collaboration, teams work together. Ideas are created and employees become part of the greater whole. They know the work they are doing will make a difference.

With open Communication, people talk about what is important and what is needed in an organization. With effective communication you tear down the walls to any misunderstandings and negativity that can foster when teams don’t know the direction.

With Innovation, companies excel and strive to create new and better ideas. It is with creativity that organizations continue to tweak and improve, to become a more profitable business.

Drive is what gets you up in the morning. It is the desire to constantly succeed and move past what is in the way and not working.

Intelligence is always needed. But when the leader is intelligent, has strong people development skills and knows how to motivate and mentor others, there is a winning formula in an organization.

Value congruence refers to the extent to which personal values are similar to the surroundings – which could be the indivdiual’s employer. It has been used to explain why subordinates are willing to follow their leader and show their loyalty and support (Burns, 1978; Shamir et al., 1993; Klein and House, 1995). The higher the value congruence , the higher the job satisfaction, loyalty, organizational citizenship and lower the stress and turnover.

The values a person holds will affect his or her employment. For example, someone who has an orientation toward strong stimulation may pursue extreme sports and select an occupation that involves fast action and high risk, such as fire fighter, police officer, or emergency medical doctor. Someone who has a drive for achievement may more readily act as an entrepreneur. Moreover, whether individuals will be satisfied at a given job may depend on whether the job provides a way to satisfy their dominant values. Therefore, understanding employees at work requires understanding the value orientations of employees.

Personality

Personality encompasses the relatively stable feelings, thoughts, and behavioural patterns of a person. Our personality differentiates us from other people, and understanding someone’s personality gives us clues about how that person is likely to act and feel in a variety of situations. In order to effectively man- age organizational behaviour, an understanding of different employees’ personalities is helpful. Having this knowledge is also useful for placing people in jobs and organizations.

The way people behave is only in part a product of their natural personality. Situations also influence how a person behaves. Are you for instance a “different person” as a student in a classroom compared to when you’re a member of a close-knit social group?

When asked to think about what our friends, enemies, family members, and colleagues are like, some of the first things that come to mind are their personality characteristics. We might think about how warm and helpful our first teacher was, how irresponsible and careless our brother is, or how demanding and insulting our first boss was. Each of these descriptors reflects a personality trait, and most of us generally think that the descriptions that we use for individuals accurately reflect their “characteristic pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours,” or in other words, their personality.

If personality is stable, does this mean that it does not change? You probably remember how you have changed and evolved as a result of your own life experiences, attention you received in early childhood, the style of parenting you were exposed to, successes and failures you had in high school, and other life events. In fact, our personality changes over long periods of time. For example, we tend to become more socially dominant, more conscientious (organized and dependable), and more emotionally stable between the ages of 20 and 40, whereas openness to new experiences may begin to decline during this same time (Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006). In other words, even though we treat personality as relatively stable, changes occur. Moreover, even in childhood, our personality shapes who we are and has lasting consequences for us. For example, studies show that part of our career success and job satisfaction later in life can be explained by our childhood personality (Judge & Higgins, 1999; Staw, Bell, & Clausen, 1986).

Is our behaviour in organizations dependent on our personality? To some extent, yes, and to some extent, no. While we will discuss the effects of personality for employee behaviour, you must remember that the relationships we describe are modest correlations. For example, having a sociable and outgoing personality may encourage people to seek friends and prefer social situations. This does not mean that their personality will immediately affect their work behaviour. At work, we have a job to do and a role to perform. Therefore, our behaviour may be more strongly affected by what is expected of us, as opposed to how we want to behave. When people have a lot of freedom at work, their personality will become a stronger influence over their behaviour (Barrick & Mount, 1993).

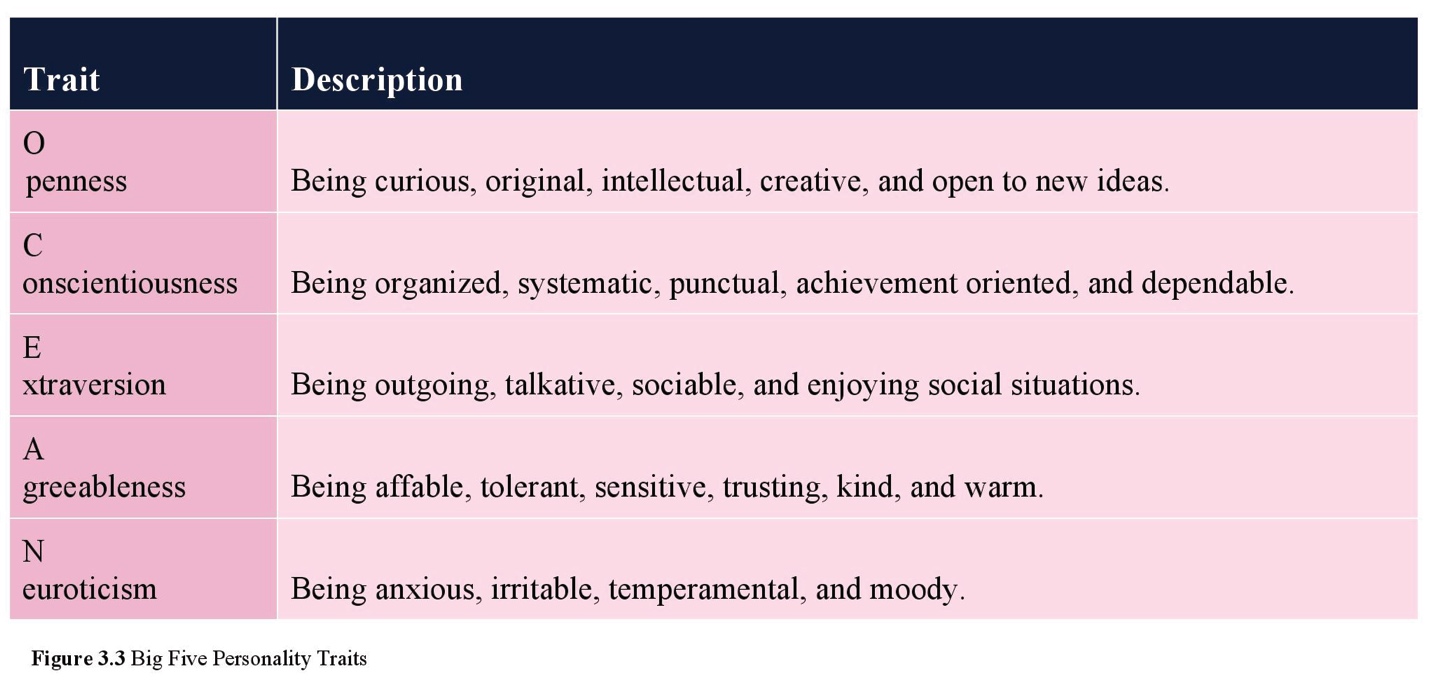

Big Five Personality Traits

How many personality traits are there? How do we even know? In every language, there are many words describing a person’s personality. In fact, in the English language, more than 15,000 words describing personality have been identified. When researchers analyzed the terms describing personality characteristics, they realized that there were many words that were pointing to each dimension of personality. When these words were grouped, five dimensions seemed to emerge that explain a lot of the variation in our personalities (Goldberg, 1990). Keep in mind that these five are not necessarily the only traits out there. There are other, specific traits that represent dimensions not captured by the Big Five. Still, understanding the main five traits gives us a good start for describing personality. A summary of the Big Five traits is presented in Figure 3.3 “Big Five Personality Traits”. Openness is the degree to which a person is curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. People high in openness seem to thrive in situations that require being flexible and learning new things. They are highly motivated to learn new skills, and they do well in training settings (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Lievens et al., 2003). They also have an advantage when they enter a new organization. Their open-mindedness leads them to seek a lot of information and feedback about how they are doing and to build relationships, which leads to quicker adjustment to the new job (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). When supported, they tend to be creative (Baer & Oldham, 2006). Open people are highly adaptable to change, and teams that experience unforeseen changes in their tasks do well if they are populated with people high in openness (LePine, 2003). Compared to people low in openness, they are also more likely to start their own business (Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Openness is the degree to which a person is curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. People high in openness seem to thrive in situations that require being flexible and learning new things. They are highly motivated to learn new skills, and they do well in training settings (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Lievens et al., 2003). They also have an advantage when they enter a new organization. Their open-mindedness leads them to seek a lot of information and feedback about how they are doing and to build relationships, which leads to quicker adjustment to the new job (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). When supported, they tend to be creative (Baer & Oldham, 2006). Open people are highly adaptable to change, and teams that experience unforeseen changes in their tasks do well if they are populated with people high in openness (LePine, 2003). Compared to people low in openness, they are also more likely to start their own business (Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Conscientiousness refers to the degree to which a person is organized, systematic, punctual, achievement oriented, and dependable. Conscientiousness is the one personality trait that uniformly predicts how high a person’s performance will be, across a variety of occupations and jobs (Barrick & Mount, 1991). In fact, conscientiousness is the trait most desired by recruiters and results in the most success in interviews (Dunn et al., 1995; Tay, Ang, & Van Dyne, 2006). This is not a surprise, because in addition to their high performance, conscientious people have higher levels of motivation to perform, lower levels of turnover, lower levels of absenteeism, and higher levels of safety performance at work (Judge & Ilies, 2002; Judge, Martocchio, & Thoresen, 1997; Wallace & Chen, 2006; Zimmerman, 2008). One’s conscientiousness is related to career success and being satisfied with one’s career over time (Judge & Higgins, 1999). Finally, it seems that conscientiousness is a good trait to have for entrepreneurs. Highly conscientious people are more likely to start their own business compared to those who are not conscientious, and their firms have longer survival rates (Certo & Certo, 2005; Zhao & Seibert, 2006).

Extraversion is the degree to which a person is outgoing, talkative, sociable, and enjoys being in social situations. One of the established findings is that they tend to be effective in jobs involving sales (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Vinchur et al., 1998). Moreover, they tend to be effective as managers and they demonstrate inspirational leadership behaviours (Bauer et al., 2006; Bono & Judge, 2004). Extraverts do well in social situations, and as a result they tend to be effective in job interviews. Part of their success comes from how they prepare for the job interview, as they are likely to use their social network (Caldwell & Burger, 1998; Tay, Ang, & Van Dyne, 2006). Extraverts have an easier time than introverts when adjusting to a new job. They actively seek information and feedback, and build effective relationships, which helps with their adjustment (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Interestingly, extraverts are also found to be happier at work, which may be because of the relationships they build with the people around them and their relative ease in adjusting to a new job (Judge et al., 2002). However, they do not necessarily perform well in all jobs, and jobs depriving them of social interaction may be a poor fit. Moreover, they are not necessarily model employees. For example, they tend to have higher levels of absenteeism at work, potentially because they may miss work to hang out with or attend to the needs of their friends (Judge, Martocchio, & Thoresen, 1997).

Agreeableness is the degree to which a person is nice, tolerant, sensitive, trusting, kind, and warm. In other words, people who are high in agreeableness are likeable people who get along with others. Not surprisingly, agreeable people help others at work consistently, and this helping behaviour is not dependent on being in a good mood (Ilies, Scott, & Judge, 2006). They are also less likely to retaliate when other people treat them unfairly (Skarlicki, Folger, & Tesluk, 1999). This may reflect their ability to show empathy and give people the benefit of the doubt. Agreeable people may be a valuable addition to the team and may be effective leaders because they create a fair environment when they are in leadership positions (Mayer et al., 2007). At the other end of the spectrum, people low in agreeableness are less likely to show these positive behaviours. Moreover, people who are not agreeable are shown to quit their jobs unexpectedly, perhaps in response to a conflict they engaged in with a boss or peer (Zimmerman, 2008). If agreeable people are so nice, does this mean that we should only look for agreeable people when hiring? Some jobs may be a better fit for someone with a low level of agreeableness. Think about it: when hiring a lawyer, would you prefer a kind and gentle person, or a pit bull? Also, high agreeableness has a downside: agreeable people are less likely to engage in constructive and change-oriented communication (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). Disagreeing with the status quo may create conflict and agreeable people are inclined to avoid creating such conflicts, missing an opportunity for constructive change.

Neuroticism refers to the degree to which a person is anxious, irritable, aggressive, temperamental, and moody. These people tend to have emotional adjustment problems and experience stress and depression on a habitual basis. People very high in neuroticism experience several problems at work. For example, they are less likely to be someone people go to for advice and friendship (Klein et al., 2004). In other words, they may experience relationship difficulties. They tend to be habitually unhappy in their jobs and report high intentions to leave, but they do not actually leave their jobs (Judge, Heller, & Mount, 2002; Zimmerman, 2008). Being high in neuroticism seems to be harmful to one’s career, as they have lower levels of career success (measured with income and occupational status achieved in one’s career). Finally, if they achieve managerial jobs, they tend to create an unfair climate at work (Mayer et al., 2007).

Scores on the Big Five traits are mostly independent. That means that a person’s standing on one trait tells very little about their standing on the other traits of the Big Five. For example, a person can be extremely high in Extraversion and be either high or low on Neuroticism. Similarly, a person can be low in Agreeableness and be either high or low in Conscientiousness. Thus, in the Five-Factor Model, you need five scores to describe most of an individual’s personality.

In the field of psychology, the five dimensions (the ‘Big Five’) are commonly used in the research and study of personality. Since the late 20th Century, these factors have been used to measure and develop a better understanding of individual differences in personality. It’s commonly used as a pre-employment assessment—and as a basis for other personality systems.

How Accurately Can You Describe Your Big Five Personality Factors? Click here BIG5 to see how you score on these factors. This is part of your applied weekly module for the chapter.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator

Aside from the Big Five personality traits, perhaps the most well-known and most often used personality assessment is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Unlike the Big Five, which assesses traits (a distinguishing quality or characteristic, typically one belonging to a person), MBTI measures types. Assessments of the Big Five do not classify people as neurotic or extravert: it is all a matter of degrees – meaning what is your extent of being a neurotic or an extravert. These are represented in percentages. If you have done the BIG5 personality test through the link above, you would have obtaiend your results in percentage form.

MBTI on the other hand, classifies people as one of 16 types . These were created by Isabel Myers and Katharine Briggs (mother of Isabel) . Myers and Briggs created their personality typology to help people discover their own strengths and gain a better understanding of how people are different.In MBTI, people are grouped using four dimensions. Based on how a person is classified on these four dimensions, it is possible to talk about 16 unique personality types.

The goal of the MBTI is to allow respondents to further explore and understand their own personalities including their likes, dislikes, strengths, weaknesses, possible career preferences, and compatibility with other people. By helping people understand themselves, Myers and Briggs believed that they could help people select occupations that were best suited to their personality types and lead healthier, happier lives.

No one personality type is “best” or “better” than another. It isn’t a tool designed to look for dysfunction or abnormality. Instead, its goal is simply to help you learn more about yourself. The questionnaire itself is made up of four different scales.

The 4 dimensions of MBTI ( source: Research Gate)

Each type is then formed into a 4 letter code = The 16 unique personality type codes ( source: paulsohn.org)

The MBTI has extremely unreliable test-retest scores. If you retake the test after 5 weeks, there is a 50% chance you will fall into a different type. In other words, the reliability is equivalent to a coin toss.

There is no concrete evidence that the MBTI measures what it claims to measure, making the categories invalid.

Finally, the MBTI is mot comprehensive because its categories do not capture the full extent of personality. There is no measure for negative emotion, and the remaining domains lack information central to personality assessment.

More than 80 of the Fortune 100 companies used Myers-Briggs tests in some form. One distinguishing characteristic of this test is that it is explicitly designed for learning, not for employee selection purposes. In fact, the Myers & Briggs Foundation has strict guidelines against the use of the test for employee selection. Instead, the test is used to provide mutual understanding within the team and to gain a better understanding of the working styles of team members (Leonard & Straus, 1997; Shuit, 2003).

You can click on MBTI and get to know which of the 16 personality type you are.

What does your MBTI score mean.? Click here

Positive and Negative Affectivity

You may have noticed that behaviour is also a function of moods. When people are in a good mood, they may be more cooperative, smile more, and act friendlier. When these same people are in a bad mood, they may tend to be picky, irritable, and less tolerant of different opinions. Yet, some people seem to be in a good mood most of the time, and others seem to be in a bad mood most of the time regardless of what is going on in their lives. This distinction is manifested by positive and negative affectivity traits. Positive affective people experience positive moods more frequently, whereas negative affective people experience negative moods with greater frequency. Negative affective people focus on the “glass half empty” and experience more anxiety and nervousness (Watson & Clark, 1984).

Positive affective people tend to be happier at work (Ilies & Judge, 2003), and their happiness spreads to the rest of the work environment. As may be expected, this personality trait sets the tone in the work atmosphere. When a team comprises mostly negative affective people, there tend to be fewer instances of helping and cooperation. Teams dominated by positive affective people experience lower levels of absenteeism (George, 1989). When people with a lot of power are also high in positive affectivity, the work environment is affected in a positive manner and can lead to greater levels of cooperation and leading to more mutually agreeable solutions to problems (Anderson & Thompson, 2004).

Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring refers to the extent to which a person is capable of monitoring his or her actions and appearance in social situations. In other words, people who are social monitors are social chameleons who understand what the situation demands and act accordingly, while low social monitors tend to act the way they feel (Snyder, 1974; Snyder, 1987).

High social monitors are sensitive to the types of behaviours the social environment expects from them. Their greater ability to modify their behaviour according to the demands of the situation and to manage their impressions effectively is a great advantage for them (Turnley & Bolino, 2001). In general, they tend to be more successful in their careers. They are more likely to get cross-company promotions, and even when they stay with one company, they are more likely to advance (Day & Schleicher, 2006; Kilduff & Day, 1994). Social monitors also become the “go to” person in their company and they enjoy central positions in their social networks (Mehra, Kilduff, & Brass, 2001). They are rated as higher performers, and emerge as leaders (Day et al., 2002).

While they are effective in influencing other people and get things done by managing their impressions, this personality trait has some challenges that need to be addressed. First, when evaluating the performance of other employees, they tend to be less accurate. It seems that while trying to manage their impressions, they may avoid giving accurate feedback to their subordinates to avoid confrontations (Jawahar, 2001). This tendency may create problems for them if they are managers. Second, high social monitors tend to experience higher levels of stress, probably caused by behaving in ways that conflict with their true feelings. In situations that demand positive emotions, they may act happy although they are not feeling happy, which puts an emotional burden on them. Finally, high social monitors tend to be less committed to their companies. They may see their jobs as a stepping-stone for greater things, which may prevent them from forming strong attachments and loyalty to their current employer (Day et al., 2002).

Proactive Personality

Proactivity is the ability to do things in advance of an event to ensure you have maximum control. It is the opposite of reactivity, which is when you simply respond to events after they have unfolded.

Proactive personality refers to a person’s inclination to fix what is perceived as wrong, change the status quo, and use initiative to solve problems. Instead of waiting to be told what to do, proactive people take action to initiate meaningful change and remove the obstacles they face along the way.

Some examples of a proactive personality are:

- Turning Up to Work Early.

- Doing Extracurricular Work to Increase Chances of Getting a College Scholarship.

- Asking Your Professor for Advice on How to Complete An Assignment.

- Writing Daily To-Do Lists.

- Researching About a Company Before a Job Interview.

In general, having a proactive personality has a number of advantages for these people. For example, they tend to be more successful in their job searches (Brown et al., 2006). They are also more successful over the course of their careers, because they use initiative and acquire greater understanding of the politics within the organization (Seibert, 1999; Seibert, Kraimer, & Crant, 2001). Proactive people are valuable assets to their companies because they may have higher levels of performance (Crant, 1995). They adjust to their new jobs quickly because they understand the political environment better and often make friends more quickly (Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003; Thompson, 2005). Proactive people are eager to learn and engage in many developmental activities to improve their skills (Major, Turner, & Fletcher, 2006).

Despite all their potential, under some circumstances a proactive personality may be a liability for an individual or organization. Imagine a person who is proactive but is perceived as being too pushy, trying to change things other people are not willing to let go, or using their initiative to make decisions that do not serve a company’s best interests. Research shows that the success of proactive people depends on their understanding of a company’s core values, their ability and skills to perform their jobs, and their ability to assess situational demands correctly (Chan, 2006; Erdogan & Bauer, 2005).

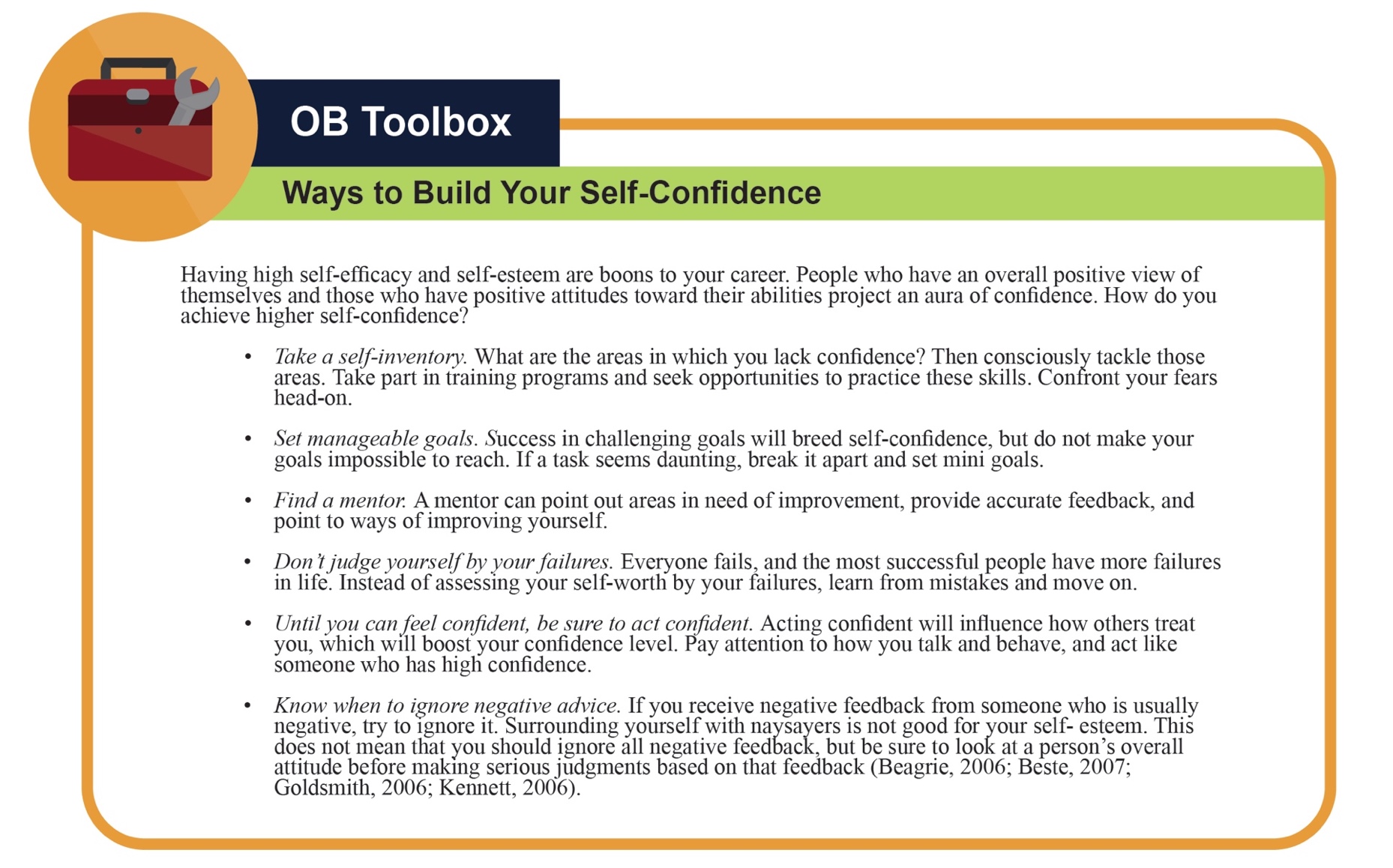

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is the degree to which a person has overall positive feelings about his or herself. People with high self-esteem view themselves in a positive light, are confident, and respect themselves. On the other hand, people with low self-esteem experience high levels of self-doubt and question their self-worth. High self-esteem is related to higher levels of satisfaction with one’s job and higher levels of performance on the job (Judge & Bono, 2001). People with low self-esteem are attracted to situations in which they will be relatively invisible, such as large companies (Turban & Keon, 1993). Managing employees with low self-esteem may be challenging at times, because negative feedback given with the intention to improve performance may be viewed as a judgment on their worth as an employee. Therefore, effectively managing employees with relatively low self-esteem requires tact and providing lots of positive feedback when discussing performance incidents.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is a belief that one can perform a specific task successfully. Research shows that the belief that we can do something is a good predictor of whether we can do it. Self-efficacy is different from other personality traits in that it is job specific. You may have high self-efficacy in being successful academically, but low self-efficacy in relation to your ability to fix your car. At the same time, people have a certain level of generalized self-efficacy where they believe that whatever task or hobby they tackle, they will reach a certain degree of success.

Studies have found that learners with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in activities that challenge them and provide opportunities to develop skills rather than easy tasks that they have already mastered. These learners are also more likely to set high goals, persevere in the face of adversity, regulate their efforts more skillfully, better manage their stress and anxiety, and perform better. In addition to these observations, they are less likely to cheat, are more likely to ask for help — for example, during assessments

Research shows that self-efficacy at work is related to job performance (Bauer et al., 2007; Judge et al., 2007; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). This relationship is probably a result of people with high self-efficacy setting higher goals for themselves and being more committed to these goals, whereas people with low self-efficacy tend to procrastinate (Phillips & Gully, 1997; Steel, 2007; Wofford, Goodwin, & Premack, 1992). Academic self-efficacy is a good predictor of your GPA, whether you persist in your studies, or drop out of college (Robbins et al., 2004).

Is there a way of increasing employees’ self-efficacy? Hiring people who can perform their tasks and training people to increase their self-efficacy may be effective. Some people may also respond well to verbal encouragement. By showing that you believe they can be successful and effectively playing the role of a cheerleader, you may be able to increase self-efficacy. Giving people opportunities to test their skills so that they can see what they can do (or empowering them) is also a good way of increasing self-efficacy (Ahearne, Mathieu, & Rapp, 2005).

Locus of Control

What do you feel when you’re suddenly faced with a tough challenge or obstacle? What thoughts go through your mind?

Do your thoughts go to how might overcome this challenge to achieve what you want? Or, do you wonder why this is happening to you or feel under attack? Do you feel paralyzed? Or, energized? Choiceless or determined?

When you are dealing with a challenge in your life, do you feel that you have control over the outcome, or do you believe that you are at the mercy of outside forces? Your answer to this question refers to your locus of control.

Our locus of control influences our response to events in our lives and our motivation to take action. If you believe that you hold the keys to your fate, you are more likely to change your situation when needed. Conversely, if you think that the outcome is out of your hands, you may be less likely to work toward change.

Individuals with high internal locus of control believe that they control their own destiny and what happens to them is their own doing, while those with high external locus of control feel that things happen to them because of other people, luck, or a powerful being.

- A student gets a good grade on a test and tells herself that she studied hard or is good at the material (internal locus of control). She gets a bad grade on another test and says the teacher doesn’t like her or the test was unfair (external locus of control).

Internals feel greater control over their own lives and therefore they act in ways that will increase their chances of success. For example, they take the initiative to start mentor-protégé relationships. They are more involved with their jobs. They demonstrate higher levels of motivation and have more positive experiences at work (Ng, Soresen, & Eby, 2006; Reitz & Jewell, 1979; Turban & Dougherty, 1994). Interestingly, internal locus is also related to one’s subjective well-being and happiness in life, while being high in external locus is related to a higher rate of depression (Benassi, Sweeney, & Dufour, 1988; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998).

The connection between internal locus of control and health is interesting, but perhaps not surprising. In fact, one study showed that having internal locus of control at the age of 10 was related to several health outcomes, such as lower obesity and lower blood pressure later in life (Gale, Batty, & Deary, 2008). It is possible that internals take more responsibility for their health and adopt healthier habits, while externals may see less of a connection between how they live and their health. Internals thrive in contexts in which they can influence their own behaviour. Successful entrepreneurs tend to have high levels of internal locus of control (Certo & Certo, 2005).

Personality Testing in Employee Selection

Personality is a potentially important predictor of work behaviour. Matching people to suitable jobs matters because when people do not fit with their jobs or the company, they are more likely to leave, costing companies as much as a person’s annual salary to replace them. In job interviews, companies try to assess a candidate’s personality and the potential for a good match, but interviews are only as good as the people conducting them. In fact, interviewers are not particularly good at detecting the best trait that predicts performance: conscientiousness (Barrick, Patton, & Haugland, 2000). One method some companies use to improve this match and detect the people who are potentially good job candidates is personality testing. Companies using them believe that these tests improve the effectiveness of their selection and reduce turnover. For example, Overnight Transportation in Atlanta found that using such tests reduced their on-the-job delinquency by 50%–100% (Emmet, 2004; Gale, 2002).

Companies hire consultants to offer pre-employment personality testing.

- These consultants provide custom benchmarks that measure a candidate’s aptitude, interests and personality. By creating job-specific profiles, a hiring manager can find the right puzzle piece to fit the team.

- these assessments are designed to help the business leader better understand his/her team, to discover how different personalities work together, ways to manage efficiently, and improve effectiveness.

Yet,are these methods good ways of selecting employees? Experts have not yet reached an agreement on this subject and the topic is highly controversial. Some experts believe, based on data, that personality tests predict performance and other important criteria such as job satisfaction. However, we must understand that how a personality test is used influences its validity.

Imagine filling out a personality test in class. You may be more likely to fill it out as honestly as you can. Then, if your instructor correlates your personality scores with your class performance, we could say that the correlation is meaningful. In employee selection, one complicating factor is that people filling out the survey do not have a strong incentive to be honest. In fact, they have a greater incentive to guess what the job requires and answer the questions to match what they think the company is looking for. As a result, the rankings of the candidates who take the test may be affected by their ability to fake results. Some experts believe that this is a serious problem (Morgeson et al., 2007; Morgeson et al., 2007). Others point out that even with faking, the tests remain valid—the scores are still related to job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1996; Ones et al., 2007; Ones, Viswesvaran, & Reiss, 1996; Tett & Christiansen, 2007). It is even possible that the ability to fake is related to a personality trait that increases success at work, such as social monitoring. This issue raises potential questions regarding whether personality tests are the most effective way of measuring candidate personality.

Scores are not only distorted because of some candidates faking better than others. Do we even know our own personality? Are we the best person to ask this question? How supervisors, coworkers, and customers see our personality matters more than how we see ourselves. Therefore, using self-report measures of performance may not be the best way of measuring someone’s personality (Mount, Barrick, & Strauss, 1994). We all have blind areas. We may also give “aspirational” answers. If you are asked if you are honest, you may think, “Yes, I always have the intention to be honest.” This response says nothing about your actual level of honesty.

There is another problem with using these tests: how good is personality at predicting performance anyway? Based on research, it’s not a particularly strong one. According to one estimate, personality only explains about 10%–15% of variation in job performance. Our performance at work depends on so many factors, and personality does not seem to be a key factor. In fact, cognitive ability (your overall mental intelligence) is a much more powerful influencer on job performance, and instead of personality tests, cognitive ability tests may do a better job of predicting who will be good performers. Personality is a better predictor of job satisfaction and other attitudes, but screening people out on the assumption that they may be unhappy at work is a challenging argument to make in the context of employee selection.

Discover what you are great at. Take this HIGH5 test.

This test is frequently applied in personal development, team building, coaching, and leadership development.

After answering 100 questions in 20 minutes, you will identify your HIGH5 or the top 5 most developed strengths free of charge.

3.4 Perception

Our behaviour is not only a function of our personality, values, and preferences, but also of the situation. We interpret our environment, formulate responses, and act accordingly. Perception may be defined as the process with which individuals detect and interpret environmental stimuli. What makes human perception so interesting is that we do not solely respond to the stimuli in our environment. We go beyond the information that is present in our environment, pay selective attention to some aspects of the environment, and ignore other elements that may be immediately apparent to other people. Our perception of the environment is not entirely rational.

For example, have you ever noticed that while glancing at a newspaper or a news website, information that is interesting or important to you jumps out of the page and catches your eye? If you are a sports fan, while scrolling down the pages you may immediately see a news item describing the latest success of your team. If you are the parent of a picky eater, an advice column on toddler feeding may be the first thing you see when looking at the page. So what we see in the environment is a function of what we value, our needs, our fears, and our emotions (Higgins & Bargh, 1987; Keltner, Ellsworth, & Edwards, 1993). In fact, what we see in the environment may be objectively, flat-out wrong because of our personality, values, or emotions. For example, one experiment showed that when people who were afraid of spiders were shown spiders, they inaccurately thought that the spider was moving toward them (Riskin, Moore, & Bowley, 1995). In this section, we will describe some common tendencies we engage in when perceiving objects or other people, and the consequences of such perceptions.

Self-Perception

Human beings are prone to errors and biases when perceiving themselves. Moreover, the type of bias people have depends on their personality.

Many people suffer from self-enhancement bias. Self-enhancement is the tendency for individuals to take all the credit for their successes, while giving little or no credit to other individuals or external factors. It could also mean overestimating our performance and capabilities and see ourselves in a more positive light than others see us. People who have a narcissistic (Narcissism is extreme self-involvement to the degree that it makes a person ignore the needs of those around them) personality are particularly subject to this bias, but many others are still prone to overestimating their abilities (John & Robins, 1994).

At the same time, other people have the opposing extreme, which may be labeled as self-effacement bias. This is the tendency for people to underestimate their performance, undervalue their capabilities, and see events in a way that puts them in a more negative light. We may expect that people with low self-esteem may be particularly prone to making this error. These tendencies have real consequences for behaviour in organizations. For example, people who suffer from extreme levels of self-enhancement tendencies may not understand why they are not getting promoted or rewarded, while those who tend to self-efface may project low confidence and take more blame for their failures than necessary.

A leader who values his or her team could say “This achievement had nothing to do with me, it is my team.” This could be considered an example of self-effacement because you understate your role and emphasize the team members.

When perceiving themselves, human beings are also subject to the false consensus error. Simply put, we overestimate how similar we are to other people (Fields & Schuman, 1976; Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). We assume that whatever behaviours we have are shared by a larger number of people than in reality.

One example of the false-consensus effect is someone believing that the political candidate that they favor has more support in the population than other candidates, even when that isn’t the case.

People who take office supplies home, tell white lies to their boss or colleagues, or take credit for other people’s work to get ahead may genuinely feel that these behaviours are more common than they really are. The problem for behaviour in organizations is that, when people believe that a behaviour is common and normal, they may repeat the behaviour more freely. Under some circumstances this may lead to a high level of unethical or even illegal behaviours.

Social Perception

How we perceive other people in our environment is also shaped by our values, emotions, feelings, and personality. Moreover, how we perceive others will shape our behaviour, which in turn will shape the behaviour of the person we are interacting with.

One of the factors biasing our perception is stereotypes. Stereotypes are generalizations based on group characteristics. Examples of stereotypes are:

- Girls should play with dolls and boys should play with trucks.

- Boys should be directed to like blue and green, girls toward red and pink.

- Asian students are better at Math than students of other nationalities.

- Women with children are less devoted to their jobs.

- Men who spend time with family are less masculine and poor breadwinners

Stereotypes may be positive, negative, or neutral. Human beings have a natural tendency to categorize the information around them to make sense of their environment. What makes stereotypes potentially discriminatory, and a perceptual bias is the tendency to generalize from a group to a particular individual. If the belief that men are more assertive than women leads to choosing a man over an equally (or potentially more) qualified female candidate for a position, the decision will be biased, potentially illegal, and unfair.

In a seminal paper, two American social psychologists experimentally demonstrated how racial stereotypes can affect intellectual ability. In their study, black participants performed worse than white participants on verbal ability tests when they were told that the test was “diagnostic” – a “genuine test of your verbal abilities and limitations”. However, when this description was excluded, no such effect was seen. Clearly these individuals experienced a stereotype threat and had negative thoughts about their verbal ability that affected their performance.

Stereotypes often create a situation called a self-fulfilling prophecy. This cycle occurs when people automatically behave as if an established stereotype is accurate, which leads to reactive behaviour from the other party that confirms the stereotype (Snyder, Tanke, & Berscheid, 1977). If you have a stereotype such as “Asians are friendly,” you are more likely to be friendly toward an Asian yourself. Because you are treating the other person better, the response you get may also be better, confirming your original belief that Asians are friendly. Of course, just the opposite is also true. Suppose you believe that “young employees are slackers.” You are less likely to give a young employee high levels of responsibility or interesting and challenging assignments. The result may be that the young employee reporting to you becomes increasingly bored at work and starts goofing off, confirming your suspicions that young people are slackers!

There are two types of self-fulfilling prophecies: Self-imposed prophecies occur when your own expectations influence your actions. For example:

- You form expectations of yourself, others, or events.

- You express those expectations verbally or nonverbally.

- Others adjust their behavior and communication to match your messages.

- Your expectations become reality.

- The confirmation strengthens your belief.

Other-imposed prophecies occur when others’ expectations influence your behavior. Your supervisor repeatedly tells you that you are not competent. Over time you start believing that you are not competent.

Selective Perception – the day that a world class violinist played at the metro station and was hardly recognized.

Stereotypes persist because of a process called selective perception. Selective perception simply means that we pay selective attention to parts of the environment while ignoring other parts. When we observe our environment, we see what we want to see and ignore information that may seem out of place. Here is an interesting example of how selective perception alters our perception to be shaped by the context: As part of a social experiment, in 2007 the Washington Post newspaper arranged Joshua Bell, the inter- nationally acclaimed violin virtuoso, to perform in a corner of the Metro station in Washington DC. The violin he was playing was worth $3.5 million, and tickets for Bell’s concerts usually cost around $100. During the rush hour in which he played for 45 minutes, only one person recognized him, only a few realized that they were hearing extraordinary music, and he made only $32 in tips (Weingarten, 2007). When you see someone playing at the metro station, would you expect them to be extraordinary?

Our background, expectations, and beliefs will shape which events we notice and which events we ignore. For example, the functional background of executives affects the changes they perceive in their environment (Waller, Huber, & Glick, 1995). Executives with a background in sales and marketing see the changes in the demand for their product, while executives with a background in information technology may more readily perceive the changes in the technology the company is using. Selective perception may perpetuate stereotypes, because we are less likely to notice events that go against our beliefs. A person who believes that men drive better than women may be more likely to notice women driving poorly than men driving poorly. As a result, a stereotype is maintained because information to the contrary may not reach their brain.

Let’s say we noticed information that goes against our beliefs. What then? Unfortunately, this is no guarantee that we will modify our beliefs and prejudices. First, when we see examples that go against our stereotypes, we tend to come up with subcategories. For example, when people who believe that women are more cooperative see a female who is assertive, they may classify this person as a “career woman.” Therefore, the example to the contrary does not violate the stereotype, and instead is explained as an exception to the rule (Higgins & Bargh, 1987). Second, we may simply discount the information. In one study, people who were either in favor of or opposed to the death penalty were shown two studies, one showing benefits from the death penalty and the other discounting any benefits. People rejected the study that went against their belief as methodologically inferior and actually reinforced the belief in their original position even more (Lord, Ross, & Lepper, 1979). In other words, trying to debunk people’s beliefs or previously established opinions with data may not necessarily help.

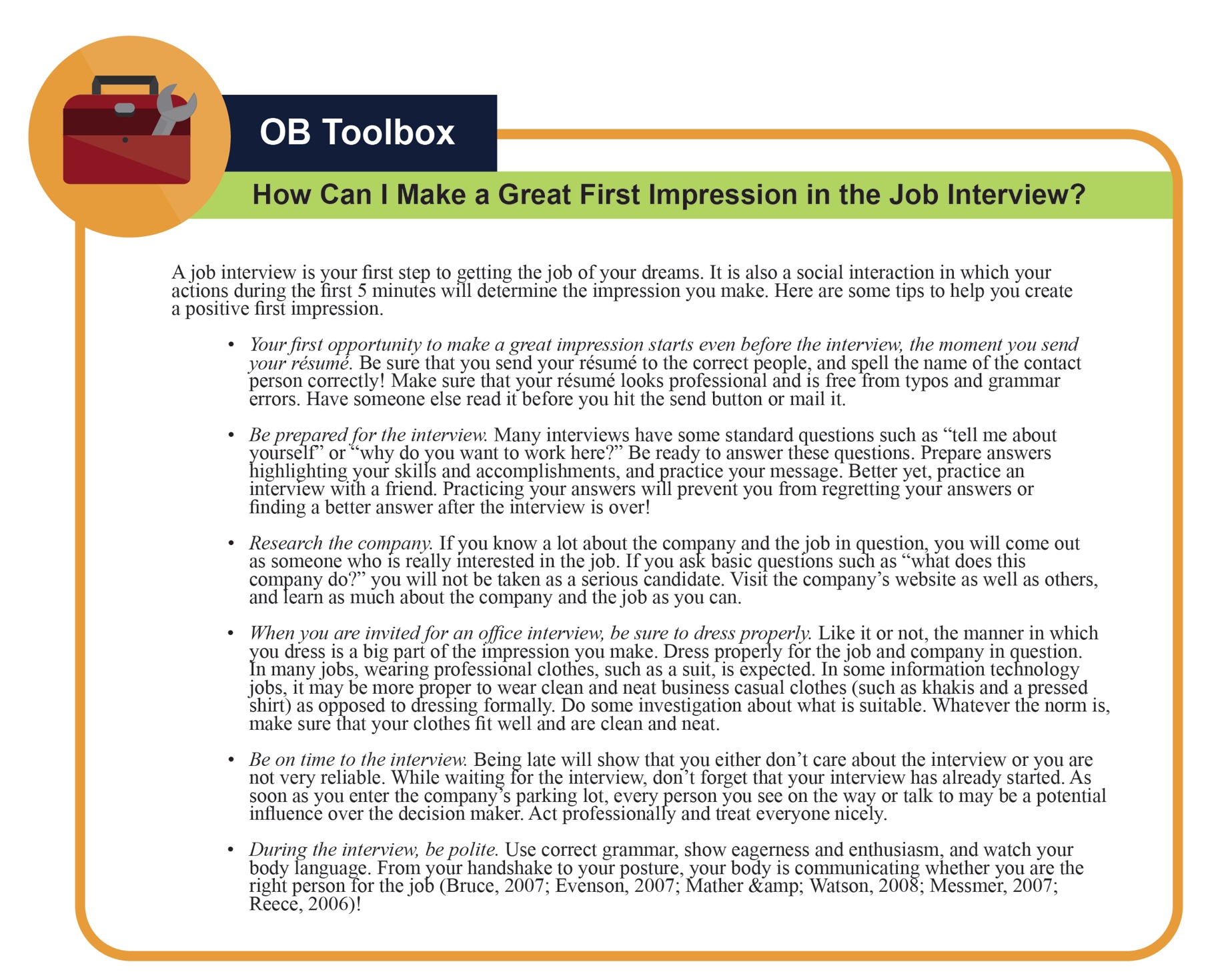

One other perceptual tendency that may affect work behaviour is that of first impressions. The first impressions we form of people tend to have a lasting impact. In fact, first impressions, once formed, are surprisingly resilient to contrary information. Even if people are told that the first impressions were caused by inaccurate information, people hold onto them to a certain degree.

The reason is that, once we form first impressions, they become independent of the evidence that created them (Ross, Lepper, & Hubbard, 1975). Any information we receive to the contrary does not serve the purpose of altering the original impression. Imagine the first day you met your colleague Anne. She treated you in a rude manner and when you asked for her help, she brushed you off. You may form the belief that she is a rude and unhelpful person. Later, you may hear that her mother is very sick and she is very stressed. In reality, she may have been unusually stressed on the day you met her. If you had met her on a different day, you could have thought that she is a really nice person who is unusually stressed these days. But chances are your impression that she is rude and unhelpful will not change even when you hear about her mother. Instead, this new piece of information will be added to the first one: She is rude, unhelpful, and her mother is sick. Being aware of this tendency and consciously opening your mind to new information may protect you against some of the downsides of this bias. Also, it would be to your advantage to pay careful attention to the first impressions you create, particularly during job interviews.

Read this guide to understand what ” first impressions” mean.

Attributions

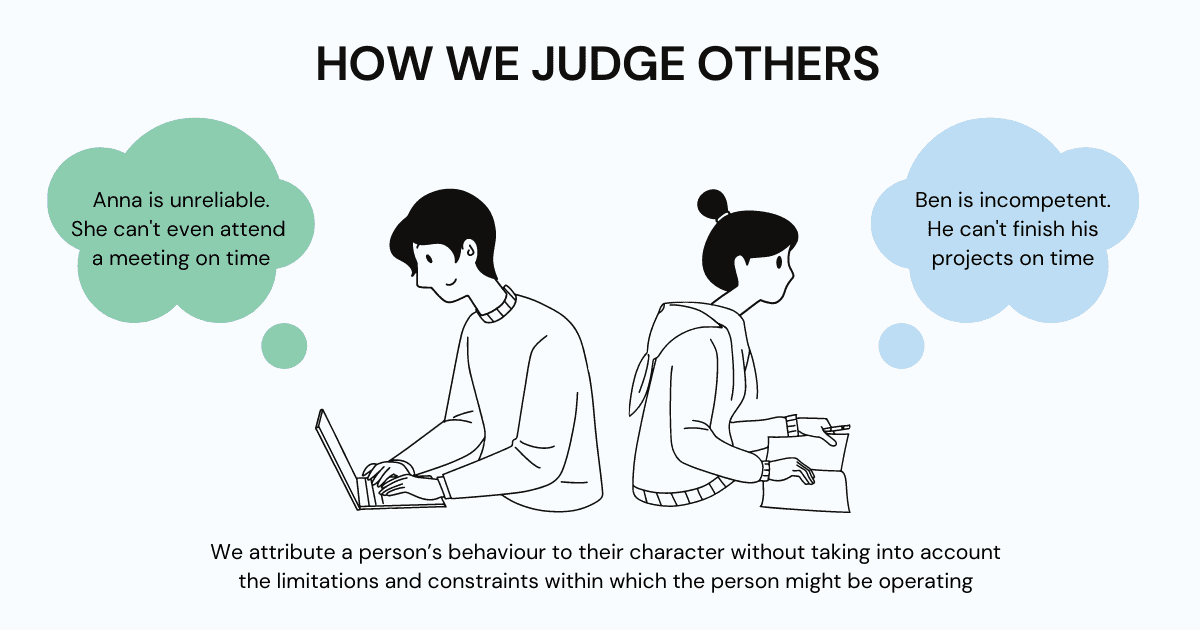

Picture source: techtello

Think of the countless times you labeled someone at work as “lazy, boring, incompetent, stupid, irritating, biased, reckless, rude…”

The lens with which you see others makes all the difference – are you quick to judge or adopt an attitude to understand?

How your co-worker reacts to a situation is shaped by their own temperament, past experiences and the current circumstances. Their behaviour in one area does not reflect who they are as a person, what they value and even how they would be in another aspect of their work.

A missed delivery deadline does not make someone incompetent, mistake is not a sign of negligence and declining meeting invite is not an act of rudeness.

Yet, we assume that’s all there is to this story.

Snap judgments without careful consideration rules our workplaces and our lives. We are quick to stamp people as “this is who they are” without taking a moment to step back and analyse the situational factors that contribute to their behaviour.

The less we know about someone, the easier it’s for us to label them and then stick with those assumptions.

This cognitive bias called fundamental attribution error or attribution bias makes us attribute a person’s behaviour to their character without taking into account the limitations and constraints within which the person might be operating.

We jump to the conclusion that their behaviour is a reflection of “who they are” without taking time to analyse the situation that makes them behave in a certain way.

An attribution is the causal explanation we give for an observed behaviour. If you believe that a behaviour is due to the internal characteristics of an actor, you are making an internal attribution. For example, let’s say your classmate Erin complained a lot when completing a finance assignment. If you think that she complained because she is a negative person, you are making an internal attribution. An external attribution is explaining someone’s behaviour by referring to the situation. If you believe that Erin complained because the finance homework was difficult, you are making an external attribution.

3.5 Using Science to Match Candidates to Jobs: The Case of Kronos

You are interviewing a candidate for a position as a cashier in a supermarket. You need someone polite, courteous, patient, and dependable. The candidate you are talking to seems nice. But how do you know who is the right person for the job? Will the job candidate like the job or get bored? Will they have a lot of accidents on the job or be fired for misconduct? Don’t you wish you knew before hiring? One company approaches this problem scientifically, saving the business time and money on hiring hourly wage employees.

Retail employers do a lot of hiring, given their growth and high turnover rate. According to one estimate, replacing an employee who leaves in retail costs companies around $4,000. High turnover also endangers customer service. Therefore, retail employers have an incentive to screen people carefully so that they hire people with the best chance of being successful and happy on the job. Unicru, an employee selection company, developed software that quickly became a market leader in screening hourly workers (Frauenheim, 2006; Rafter, 2005). The company was acquired by Massachusetts-based Kronos Inc. (NASDAQ: KRON) in 2006 and is currently owned by a private equity firm.

The idea behind the software is simple: if you have a lot of employees and keep track of your data over time, you have access to an enormous resource. By analyzing this data, you can specify the profile of the “ideal” employee. The software captures the profile of the potential high performers, and applicants are screened to assess their fit with this particular profile. More importantly, the profile is continually updated as new employees are hired. As the database gets larger, the software does a better job of identifying the right people for the job.

If you applied for a job in retail, you may have already been a part of this database: the users of this system include giants such as Universal Studios, Costco Wholesale Corporation, Burger King, and other retailers and chain restaurants. In companies such as Albertsons or Blockbuster, applicants use a kiosk in the store to answer a list of questions and to enter their background, salary history, and other information. In other companies, such as some in the trucking industry, candidates enter the data through the website of the company they are applying to. The software screens people on basic criteria such as availability in scheduling as well as personality traits.

Candidates are asked to agree or disagree with statements such as “I often make last-minute plans” or “I work best when I am on a team.” After the candidates complete the questions, hiring managers are sent a report complete with a colour-coded suggested course of action. Red means the candidate does not fit the job, yellow means proceed with caution, and green means the candidate can be hired on the spot. Interestingly, the company contends that faking answers is not easy because it is difficult for candidates to predict the desired profile. For example, according to their research, being a successful salesman has less to do with being an extraverted and sociable person and more to do with a passion for the company’s product.

Matching candidates to jobs has long been viewed as a key way of ensuring high performance and low turnover in the workplace, and advances in computer technology are making it easier and more efficient to assess candidate–job fit. Companies using such technology are cutting down the time it takes to hire people, and it is estimated that using such technologies lowers their turnover by 10%–30% (Berta, 2002; Frazier, 2005; Haaland, 2006; Overholt, 2002).

3.6 Conclusion

In this chapter we have reviewed major individual differences that affect employee attitudes and behaviours. Our values and personality explain our preferences and the situations we feel comfortable with. Personality may influence our behaviour, but the importance of the context in which behaviour occurs should not be neglected. Many organizations use personality tests in employee selection, but the use of such tests is controversial because of problems such as faking and the low predictive value of personality for job performance. Perception is how we interpret our environment. It is a major influence over our behaviour, but many systematic biases colour our perception and lead to misunderstandings.