Chapter 2: Managing Demographic and Cultural Diversity

Chapter Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to know and learn the following:

- How to explain the meaning and difference between Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (D.E.& I.)

- How to explain the benefits of managing diversity.

- How to describe challenges of managing a workforce with diverse demographics.

- How to describe the challenges of managing a multicultural workforce.

Introduction

In 2013, Qantas, Australia’s national airline, posted a record loss of AUD$2.8 billion. This low point in the airline’s 98-year history followed record-high fuel costs, the grounding of its A380s in 2010 for engine trouble, and the suspension of its entire fleet for three days in 2011 after a series of bitter union disputes. Across the country, predictions surrounding the fate of Australia’s national carrier were extremely serious.

Fast-forward to 2017, and the situation couldn’t be more different. Qantas delivered a record profit of AUD$850 million, increased its operating margin to 12 percent, won the “World’s Safest Airline” award, ranked as Australia’s most trusted big business and its most attractive employer, and delivered shareholder returns in the top quartile of its global airline peers.

Transformation is an overused word, but for Qantas it’s a perfect description. How did it happen? The company’s 2017 Investor Roadshow briefing sounded like a textbook in disciplined operational and financial management, as well as employee, customer, and shareholder focus. Yet for CEO Alan Joyce, the spectacular turnaround reflects an underlying condition: “We have a very diverse environment and a very inclusive culture.” Those characteristics, according to Joyce, “got us through the tough times . . . diversity generated better strategy, better risk management, better debates, and better outcomes.”

When you’re building a team, you don’t want twenty people who all think, act and believe the same. You want a thriving workplace where everyone has different perspectives and can bring new and exciting ideas to the table.

When diversity, equity and inclusion are brought up, they tend to be banded together. Though this is common, it’s important to note that they mean completely different things.

Whilst it’s true that you can’t have one without the other, there are key differences that separate the three.

But what exactly is the difference ?We’ll take a closer look at the differences and how making sure that workplaces have plenty of each, is important.

First, a video based introduction.

To sumamrise:

Diversity can be defined as the practice of including people from a range of different aspects of life. These could be personal, physical and social characteristics. This includes but is not limited to gender, ethnicity, age, income and education. It can also be various physical or mental disabilities and sexual orientation. It fundamentaly relates to social differences among employees.

Equity aims to ensure the fair treatment, (we will earn about the Equity Theory in Chapter 5) access, equality of opportunity and advancement for everyone while also attempting to identify and remove the barriers that have prevented some groups from fully participating. As such, companies that adopt equity practices don’t establish one-size-fits-all policies. Rather they take individual needs into consideration, while also readjusting organizational structures to account for the disadvantages minority groups face.

Inclusion builds a culture where everyone feels welcome by actively inviting every person or every group to contribute and participate. This inclusive and welcoming environment supports and embraces differences and offers respect to everyone in words and actions. A work environment that’s inclusive is supportive, respectful and collaborative and aims to get all employees to participate and contribute. It consists of belonging, fair treatment, integrating differences, trust, collaborative decision-making and psychological safety.An inclusive work environment endeavors to remove all barriers, discrimination and intolerance.

In business, this is the ability to integrate everyone within the workplace and create a safe and inclusive atmosphere. It’s allowing people’s differences to coexist in a mutually beneficial way.

This chapter will focus on the management of diversity.

Doing Good as a Core Business Strategy: The Case of Goodwill Industries

Goodwill Industries International has been an advocate of diversity for over 100 years. In 1902, in Boston, Massachusetts, a young missionary set up a small operation enlisting struggling immigrants in his parish to clean and repair clothing and goods to later sell. This provided workers with the opportunity for basic education and language training. His philosophy was to provide a “hand up,” not a “hand out.” Although today you can find retail stores in over 2,300 locations worldwide, and in 2009 more than 64 million people in the United States and Canada donated to Goodwill, the organization has maintained its core mission to respect the dignity of individuals by eliminating barriers to opportunity through the power of work. Goodwill accomplishes this goal, in part, by putting 84% of its revenue back into programs to provide employment, which in 2008 amounted to $3.23 billion. As a result of these programs, every 42 seconds of every business day, someone gets a job and is one step closer to achieving economic stability.

Goodwill is a pioneer of social enterprise and has managed to build a culture of respect through its diversity programs. If you walk into a local Goodwill retail store, you are likely to see employees from all walks of life, including differences in gender and race, physical ability, sexual orientation, and age. Goodwill provides employment opportunities for individuals with disabilities, lack of education, or lack of job experience. The company has created programs for individuals with criminal backgrounds who might otherwise be unable to find employment, including basic work skill development, job placement assistance, and life skills. In 2008, more than 172,000 people obtained employment, earning $2.3 billion in wages and gained tools to be productive members of their community. Goodwill has established diversity as an organizational norm, and as a result, employees are comfortable addressing issues of stereotyping and discrimination. In an organization of individuals with such wide-ranging backgrounds, it is not surprising that there are a wide range of values and beliefs.

Management and operations are decentralized within the organization with 166 independent community- based Goodwill stores. These regional businesses are independent, not-for-profit human services organizations. Despite its decentralization, the company has managed to maintain its core values. Seattle’s Goodwill is focused on helping the city’s large immigrant population and individuals without basic education and English language skills. At Goodwill Industries of Kentucky, the organization recently invested in custom software to balance daily sales at stores to streamline operations so managers can spend less time on paperwork and more time managing employees.

Part of Goodwill’s success over the years can be attributed to its ability to innovate. As technology evolves and such skills became necessary for most jobs, Goodwill has developed training programs to ensure that individuals are fully equipped to be productive members of the workforce, and in 2008 Goodwill was able to provide 1.5 million people with career services. As an organization, Goodwill itself has entered into the digital age. You can now find Goodwill on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube. Goodwill’s business practices encompass the values of the triple bottom line of people, planet, and profit. The organization is taking advantage of new green initiatives and pursuing opportunities for sustainability. For example, at the beginning of 2010, Goodwill received a $7.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Labor, which will provide funds to prepare individuals to enter the rapidly growing green industry of their choice. Oregon’s Goodwill Industries has partnered with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and Oregon E-Cycles program to prevent the improper disposal of electronics. Goodwill discovered long ago that diversity is an advantage rather than a hindrance (Goodwill Industries of North Central Wisconsin, 2009; Slack, 2009; Tabafunda, 2008; Walker, 2008).

2.1 Demographic Diversity

2.1 Demographic Diversity

The word demography comes from two ancient Greek words, demos, meaning “the people,” and graphy, meaning “writing about or recording something” — so literally demography means “writing about the people.” A demographer is someone who studies a human population’s size, structure, distribution and its characteristics – like age, gender, income, race, religion, ethnicity and culture.

Canada is a multicultural country. Canadians come from a vast range of nations, races, religions and heritage. This multicultural diversity comes from centuries of immigration. As a result, a demographically diverse population is now one of the distinctive features of Canadian society.

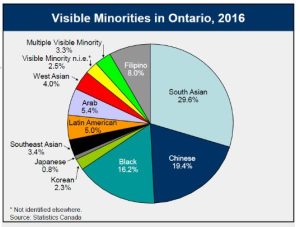

The pie chart alongside, from Statistics Canada, shows Canada’s visible minority presence. A visible minority is defined by the Government of Canada as “persons, other than aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour”. The term is used primarily as a demographic category by Statistics Canada, in connection with that country’s Employment Equity policies. ( source: Wikipedia)

Almost a quarter of Canada’s people were or are immigrants or permanent residents — who now account for their largest share of the population in the country’s history, according to new census data from Statistics Canada released in October 2022.

Statistics Canada reports that 8.3 million people, or 23 per cent of the population, fit into this category, topping the previous record of 22.3 per cent in 1921.

Immigrants and permanent residents now make up a larger share of Canada’s population than they do in any other G7 country.

“If these trends continue, based on Statistics Canada’s recent population projections, immigrants could represent from 29.1 per cent to 34 per cent of the population of Canada by 2041,” the report said.

Between 2016 and 2021, 1.3 million new immigrants settled permanently in Canada. Almost 16 per cent of all immigrants in Canada came to the country recently.

Learning Outcomes

- Explain the benefits of managing diversity effectively.

- Explain the challenges of diversity management.

Benefits of Diversity

What is the business case for diversity? Having and managing a diverse workforce effectively has the potential to bring about several benefits to organizations.

1.Higher Creativity in Decision Making

An important potential benefit of having a diverse workforce is the ability to make higher quality decisions. In a diverse work team, people will have different opinions and perspectives. In these teams, individuals are more likely to consider more alternatives and think outside the box when making decisions. Research also shows that diverse teams tend to make higher quality decisions (McLeod, Lobel, & Cox, 1996).

There’s a fascinating correlation between being exposed to other cultures and creativity. So, what is it about multicultural experiences that enhances creativity?

Forbes reports that diverse teams are more creative because a person’s individual creativity is enhanced by their ability to integrate different points of view—something that many of us learn when interacting with people from different backgrounds. In fact, multicultural experiences have been found to improve awareness of the underlying connections between different ideas, as well as enhance idea flexibility.

Therefore, having a diverse workforce may have a direct impact on a company’s bottom line by increasing creativity and innovation in decision making.

2.Better Understanding and Service of Customers

A company with a diverse workforce may create products or services that appeal to a broader customer base. For example, PepsiCo Inc. planned and executed a successful diversification effort in the recent past. The company was able to increase the percentage of women and ethnic minorities in many levels of the company, including management. The company points out that in 2004, about 1% of the company’s 8% revenue growth came from products that were inspired by the diversity efforts, such as guacamole- flavored Doritos chips and wasabi-flavored snacks. Similarly, through Jazz Aviation’s formal “Jazz Lends a Hand” community program, employees can apply for a paid day off to volunteer with a charity of their choosing. Jazz Aviation offers scholarships to students enrolled in Aircraft Maintenance Engineer (AME) programs at local community colleges and provides mentoring to apprentice AMEs. In addition, the company maintains a tool purchase program, an interest-free payment program to help AMEs spread the cost of tools over an extended period. “For Jazz, diversity is not a program, it is core to the makeup of our people and business. To be a leader in our industry and to have a competitive advantage, Jazz celebrates differences and values the uniqueness that everyone has to offer” (Chorus Aviation Inc., 2019).

A company with a diverse workforce may understand the needs of groups of customers better, and customers may feel more at ease when they are dealing with a company that understands their needs.

3.More Satisfied Workforce

When employees feel that they are fairly treated, they tend to be more satisfied. On the other hand, when employees perceive that they are being discriminated against, they tend to be less attached to the company, less satisfied with their jobs, and experience more stress at work (Sanchez & Brock, 1996). Organizations where employees are satisfied often have lower turnover. Organisational diversity initiatives must fit in with company culture.

Mastercard consistently makes it into the Top 10 of DiversityInc’s 50 Best Companies for Diversity list. They believe that “diversity is what drives better insights, better decisions, and better products. It is the backbone of innovation”. A particularly unique project that Mastercard has executed over the past few years involves getting older employees in the company more active when it comes to social media. To address generational barriers, “YoPros” BRG (the Young Professionals Business Resource Group) offers a one-on-one ‘Social Media Reverse Mentoring’ program to older employees who want to become familiarised with the platforms.

At Coca-Cola, diversity is seen “as more than just policies and practices. It is an integral part of who we are as a company, how we operate and how we see our future.” With its new paid family leave policy for all parents and caregivers, Coca-Cola is committing to the health and well-being of all employees and their families. Many LGBT people build their families through adoption, and additional time at home helping a baby or child transition into a new family environment is important. Likewise, for single parents who are LGBT, this extended paid leave allows more time to secure their child’s well-being, including finding reliable childcare.

4.Market Reputation

Companies that do a better job of managing a diverse workforce are often rewarded in the stock market, indicating that investors use this information to judge how well a company is being managed.

Although gender, generations and sexual orientation are all part of the diversity hiring strategy at Sodexo, (a French food services and facilities management company that operates in 55 countries) they state that “gender balance is our business”, and their mission is to make it everyone else’s business too. 55% of all staff members in Sodexo are women – that’s up from just 17% in 2009. 58% of the members on the board of directors are female and the company runs 14 Gender Balance Networks worldwide. What they have found is that when there is an optimal gender balance within an organisation, employee engagement increases by 4 percentage points, gross profit increases by 23% and brand image strengthens by 5 percentage points.

The Candian Women’s Foundation states that women make up just over half of the Canadian population, yet continue to be underrepresented in political and professional leadership positions. Barriers to leadership multiply for women who face intersecting forms of discrimination, such as racism, colonialism, ableism, (discrimination in favor of able-bodied people) and homophobia (the fear, hatred, discomfort with, or mistrust of people who are lesbian, gay, or bisexual). This has a significant impact on organisations that have biased preferences and could lead to poor reputation and business results.

Ekta Mendhi is Vice President- Technology, Infrastructure and Innovation at CIBC in Canada. She had served as the co-chair of Women in Capital Markets’, Women in Leadership Network, and co-founded the Canadian Gender and Good Governance Alliance. They found through their research that creating a more diverse board of directors can enhance decision-making process and augment an organization’s performance and market reputation (Mendhi & Dart, 2018).

New industries such as the Canadian Cannabis industry is not exempt from these diversity considerations. A report by Marijuana Business Daily reports that “Cannabis companies in Canada with “monoculture and mono-gender” boardroom compositions could face a competitive disadvantage and will ultimately take a hit to their bottom lines” (Lamers, 2019).

5.Lower Litigation Expenses

Companies doing a particularly bad job in diversity management face costly litigations. When an employee or a group of employees feel that the company is violating equity laws, they may file a complaint.

Shareholders interested in corporate diversity and inclusion practices and workplace culture are turning more toward litigation as a tool to hold companies accountable.

A shareholder suit against Tesla Inc. in June 2022 is an example of this emerging tactic. The suit accuses the electric-vehicle maker’s officers and directors of allowing a “toxic workplace culture” to fester at the company, exposing Tesla to potential liability.

The case stems from allegations of racial discrimination and harassment at Tesla’s factory near San Francisco.

Both executives and investors watch these cases closely and do what they can to avoid being next, said John Streur, chief executive officer of Calvert Research and Management.

“So, when you see media attention, when you see inquiries, when you see reports, and when you see all this happening—it does stimulate change,” Streur said. “And no executive wants to be in that position.”

Google Inc. parent company Alphabet Inc. settled a similar suit related to sexual misconduct in 2020 for a $310 million commitment to diversity and equity initiatives.

L Brands Inc., which once owned Victoria’s Secret, last year agreed to spend $90 million to change its corporate practices as part of a settlement of shareholder lawsuits alleging a toxic culture of sexual harassment and misogyny.

Microsoft Corp. told its shareholders in April 2016 that it would work on closing its gender pay gap, which was $0.02 on the dollar at the time. (This means if the male employee earned $100,00 in salary , the woman earned $2000 less , only $98,000) .By 2017, the company reported achieving equal pay for men and women.

The Ministry of Labour (MOL) in Canada acts as a mediator between the company and the person in cases where litigation is claimed due to unfair or unequal hiring practices, and the company may choose to settle the case outside the court. If no settlement is reached, the MOL may sue the company on behalf of the complainant or may provide the injured party with a right-to-sue letter. Regardless of the outcome, these lawsuits are expensive and include attorney fees as well as the cost of the settlement or judgment, which may reach millions of dollars. The resulting poor publicity also has a cost to the company. The Canadian Employment Equity Act has a mandate to “encourage the establishment of working conditions that are free of barriers, corrects the conditions of disadvantages in employment and promotes the principle that employment equity requires special measures and the accommodation of differences for the four designated groups in Canada” (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2018).

The Employment Equity Act identifies and defines the designated groups as:

- Women

- Aboriginal peoples – Indian, Inuit or Métis;

- Persons with disabilities; and

- Members of visible minorities

If you’re interested in reading about more legal cases related to diversity and discrimination, The Ontario Human Rights Legal Support Centre has a description of recent cases related to diversity and discrimination where you can see the latest outcomes of those cases: http://www.hrlsc.on.ca/en/human-rights-stories/winning-human-rights-hearing/more-cases. In summary, effective management of diversity can lead to big cost savings by decreasing the probability of facing costly and embarrassing lawsuits.

6.Higher Company Performance

If a company isn’t viewed as being inclusive, some customers (including both in the B2B and B2C marketplaces) may shy away from giving you their business.

This is especially true with Millennial (anyone born from 1981 to 1996) and Gen Z (anyone born from 1997 to 2012) customers. These two generations are incredibly socially conscious. As a result, they may prefer inclusive companies when considering purchases in both their personal and professional lives. If you aren’t seen as supporting diversity, you may miss out on opportunities to increase sales, foster strong customer relationships, and ultimately enhance your profitability.

As a result of all these potential benefits, companies that manage diversity more effectively tend to outperform others. Research shows that there is a positive relationship between racial diversity of the company and company performance (Richard, 2000). Companies ranked in the Diversity 50 list created by DiversityInc magazine performed better than their counterparts (Slater, Weigand, & Zwirlein, 2008).

Challenges of Diversity

If managing diversity effectively has the potential to increase company performance, increase creativity, and create a more satisfied workforce, why aren’t all companies doing a better job of encouraging diversity? Despite all the potential advantages, there are also several challenges associated with increased levels of diversity in the workforce.

1.Similarity-Attraction Phenomenon

There is a tendency for people to be attracted to people similar to themselves (Riordan & Shore, 1997). Research shows that individuals communicate less frequently with those who are perceived as different from themselves (Chatman et al., 1998). They are also more likely to experience emotional conflict with people who differ with respect to race, age, and gender (Jehn, Northcraft, & Neale, 1999; Pelled, Eisenhardt, & Xin, 1999). Individuals who are different from their team members are more likely to report perceptions of unfairness and feel that their contributions are ignored (Price, Harrison, & Gavin, 2006).

The similarity-attraction phenomenon may explain some of the potentially unfair treatment based on demographic traits. It embodies the popular adage, “birds of a feather flock together.”

If a hiring manager chooses someone who is racially similar over a more qualified candidate from a different race, the decision will be unfair. In other words, similarity-attraction may prevent some highly qualified women, minorities, or persons with disabilities from being hired. Of course, the same tendency may prevent highly qualified Caucasian and male candidates from being hired as well but given that Caucasian males are more likely to hold powerful management positions in today’s Canadian based organizations, similarity-attraction may affect women and minorities to a greater extent. Even when candidates from minority or underrepresented groups are hired, they may receive different treatment within the organization.

For example, research shows that one way in which employees may get ahead within organizations is through being mentored by a knowledgeable and powerful mentor. Yet, when the company does not have a formal mentoring program in which people are assigned a specific mentor, people are more likely to develop a mentoring relationship with someone who is similar to them in demographic traits (Dreher & Cox, 1996). This means that those who are not selected as protégés will not be able to benefit from the support and advice that would further their careers. Similarity-attraction may even affect the treatment people receive daily. If the company CEO constantly invites a male employee to play golf with him while a female employee never receives the invitation, the male employee may have a serious advantage when important decisions are made

2.Faultlines

A faultline is an attribute along which a group is split into subgroups. For example, in a group with three female and three male members, gender may act as a faultline because the female members may see themselves as separate from the male members. Now imagine that the female members of the same team are all over 50 years old and the male members are all younger than 25. In this case, age and gender combine to further divide the group into two subgroups. Teams that are divided by faultlines experience a number of difficulties. For example, members of the different subgroups may avoid communicating with each other, reducing the overall cohesiveness of the team. Research shows that these types of teams make less effective decisions and are less creative (Pearsall, Ellis, & Evans, 2008; Sawyer, Houlette, & Yeagley, 2006). Faultlines are more likely to emerge in diverse teams, but not all diverse teams have faultlines. Going back to our example, if the team has three male and three female members, but if two of the female members are older and one of the male members is also older, then the composition of the team will have much different effects on the team’s processes. In this case, age could be a bridging characteristic that brings together people divided across gender.

Research shows that even groups that have strong faultlines can perform well if they establish certain norms. When members of subgroups debate the decision topic among themselves before having a general group discussion, there seems to be less communication during the meeting on pros and cons of different alternatives. Having a norm stating that members should not discuss the issue under consideration before the actual meeting may be useful in increasing decision effectiveness (Sawyer, Houlette, & Yeagley, 2006).

3.Stereotypes

Your boss informed you that they need your assistance in training a new hire, Unax Uceda, in two weeks. Stop right there. What went through your mind when you read the new hire’s name? Did you make any assumptions about the person based on their name? To process all the information you’re exposed to on a daily basis, your brain creates shortcuts, which are called stereotypes.

Stereotypes are generalizations about a particular group of people. This stereotype may be based on your past experience with someone of a similar age, gender, ethnicity, background, education, etc., or your cultural biases and prejudices (which we all have). An important challenge of managing a diverse workforce is the possibility that stereotypes about different groups could lead to unfair decision making.

The assumption that women are more relationship oriented, while men are more assertive is an example of a stereotype. The problem with stereotypes is that people often use them to make decisions about a particular individual without actually verifying whether the assumption holds for the person in question. As a result, stereotypes often lead to unfair and inaccurate decision making. For example, a hiring manager holding the stereotype mentioned above may prefer a male candidate for a management position over a well-qualified female candidate. The assumption would be that management positions require assertiveness and the male candidate would be more assertive than the female candidate.

Stereotyping can cause low morale for the individual or group impacted and could potentially make for a toxic work environment. Employees who face constant comments, criticisms or other negative results from stereotyping can lose motivation and interest in performing their jobs, lower their productivity and lead to turnover. Stereotype threats can reduce job engagement, career aspirations, and receptivity to feedback.

Workplace stereotyping has short and long-term consequences. Let’s review three effects.

- Culture. Company culture has a substantial impact on profitability. Workplace stereotypes are a massive roadblock to improving culture because it hampers employees’ sense of belonging at the company.

- Talent. Stereotyping can prevent hiring managers from finding the best candidate for the job or prevent applicants from even wanting to apply to your positions. Candidates often screen companies using various websites (for example glassdoor. ca in Canada) to get an insider view before applying. Here are a few things they will take notice of.

- Are all senior leadership one gender or ethnicity?

- Are all the pictures of one ethnic group, or is there diversity?

- They might review your company’s LinkedIn account to get a feel for how long people stay at the company. If they find someone like them, they may reach out about the employee’s experience of working for you.

- There are many company review websites that allow candidates to read employee or previous employees’ comments about working for the company and how they felt about leadership.

- Legal. If workplace stereotypes go unchecked, they can lead to workplace discrimination. Being sued for workplace discrimination takes time and financial resources and damages your company’s image.

Being aware of stereotypes is the first step to preventing them from affecting decision making.

4.Neurodiversity

If you perceive your classmate to be a slow learner, highly erratic in behaviour, unable to make eye contact, displays variability socially, in learning, attention and moods, would you consider this classmate to be disabled? Would you classify your classmate as a disabled stereotype?

Virgin billionaire Richard Branson – perhaps the business icon of our times – created a multi-billion dollar empire across industries such as music, media, and travel.

Branson – who has ADHD and dyslexia – has credited these conditions with his business success, saying on his own website of his dyslexia ‘”I see my condition as a gift, not a disability. It has helped me learn the art of delegation, focus my skills, and work with incredible people.”

Ingvar Kamprad was a Swedish business magnate and the founder of IKEA. Kamprad was both dyslexic and an ADHDer – it was his difficulties remembering product codes that led to IKEA’s famously creative furniture names (chairs and desks have men’s names, garden furniture uses names of Swedish islands, and so on…) This ended up being one of the defining aspects of the ultra-successful brand.Kamprad was also a great example of the positive ADHDer traits of high energy, drive, and creativity.

During one of Musk’s guest appearances, the entrepreneur, billionaire and business icon announced that he is on the autism spectrum. This announcement sparked many conversations about neurodiversity globally. “I don’t always have a lot of intonation or variation in how I speak … which I’m told makes for great comedy. I’m actually making history tonight as the first person with Asperger’s to host SNL( an American TV show) … So, I won’t make a lot of eye contact with the cast tonight. But don’t worry, I’m pretty good at running ‘human’ in emulation mode.”

Neurodiversity describes the idea that neurological differences like autism, ADHD, and dyslexia are natural human variations that have benefits. The term “neurodivergent” describes people whose brain differences affect how their brain works. That means they have different strengths and challenges from people whose brains don’t have those differences. The possible differences include medical disorders, learning disabilities and other conditions. The possible strengths include better memory, being able to mentally picture three-dimensional (3D) objects easily, the ability to solve complex mathematical calculations in their head, and many more.

Neurodivergent isn’t a medical term. Instead, it’s a way to describe people using words other than “normal” and “abnormal.” That’s important because there’s no single definition of “normal” for how the human brain works.

The word for people who aren’t neurodivergent is “neurotypical.” That means their strengths and challenges aren’t affected by any kind of difference that changes how their brains work.

Dr. Nick Walker, a leading thinker in the emergent field of neurodiversity studies, says,” Neurodiversity is a natural, healthy, and important form of human biodiversity — a fundamental and vital characteristic of the human species, a crucial source of evolutionary and creative potential.”

Research has shown that people with autism often outperform others in auditory and visual tasks and do better on non-verbal tests of intelligence. A study by University of Montreal found that in a test that involved completing a visual pattern, people with autism finished 40% faster than those without the condition.

“Ideally, they would be employed in fields that don’t require constant group meetings, like programming, software developing, scientific research work or music,” says Ritika Aggarwal, consultant psychologist at Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre in India.

What neurodiverse persons may lack in social skills, they can make up for with other talents such as attention to detail, the ability to stick to a routine, and to recognise patterns. A person with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), for example, can bring in creativity and innovation, and not get tired easily.

“When you bring in these other perspectives to the organisation, your company is more likely to succeed,” she says. It is a way to innovate, and that requires fresh perspectives.

We have to first get rid of our assumptions about neurodiversity and find the right person for the right job based on individual strengths and interests.

Click on this webiste: Unique job site can help neurodivergent people find meaningful work — while being themselves

Some commonly occuring neurodivergent behaviors

ADHD – Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder- is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. It is usually first diagnosed in childhood and often lasts into adulthood. Children with ADHD may have trouble paying attention, controlling impulsive behaviors (may act without thinking about what the result will be), or be overly active.

Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), refers to a broad range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, speech and nonverbal communication.

Dyslexia is a learning disorder that involves difficulty reading due to problems identifying speech sounds and learning how they relate to letters and words (decoding). Also called a reading disability, dyslexia is a result of individual differences in areas of the brain that process language.

Is being neurodivergent a disability?

Some neurodivergent people struggle because of systems or processes that don’t give them a chance to show off their strengths or that create new or more intense challenges for them.

- Example #1: Many people who are neurodivergent struggle in social situations, which can make it hard to find work because they struggle during job interviews. However, they can still get the job if the hiring process emphasizes their abilities, such as screening potential hires with a skills test. Once on the job, their attention to detail means they’re an outstanding accountant or record-keeper because they can easily process data that others might find more tedious.

- Example #2: Some who are neurodivergent struggle in noisy environments or situations. That means a busy office can feel overwhelming to them. However, a pair of noise-canceling headphones might give them the quiet they need to make them the most productive person on their team because one of their strengths is the ability to focus on their work intensely.

In both examples, accommodations helped the person overcome their particular struggle. For someone with a disability, an accommodation is a way to accept that they’re different or have challenges, and then give them a tool or a way to succeed. For the people who are neurodivergent in the examples above, the accommodations were the hiring process and the headphones.

How do we connect productively with neurodivergent people.? Be patient, be empathetic, be supportive and be kind. This link on valuing differences gives you practical advice on how to conduct yourself when your classmate or even your colleague at work displays certain characteristics that seem odd with what you would consider “normal” behaviour.

Mini Case Scenario

Xeron Corp. is a software development company that had hired several employees with ASD, ADHD, and Dyslexia. While these employees were highly skilled and talented, the company was facing challenges in managing them due to the nature of their conditions.

One of the primary challenges was communication. Some of the employees with ASD had difficulty with social communication, which made it hard for them to communicate effectively with their colleagues. They also had difficulty interpreting nonverbal cues, which led to misunderstandings and conflicts with their colleagues.

Another challenge was work organization. Some employees with ADHD had difficulty with task prioritization and time management, which affected their productivity and ability to meet deadlines. Employees with Dyslexia also had challenges with written communication, which made it hard for them to write reports and documents.

Xeron wants to adopt measures that result in a more inclusive and supportive work environment for the neuro-diverse employees including those with ADHD, Dyslexia so that they feel more valued and supported, thereby leading to increased job satisfaction and productivity.

The company is asking you to develop and implement a program containing specific measures for each of the identified groups of its neuro-diverse employees.

What specific measures will you propose?

Suggestions for Managing Diversity

What can organizations do to manage diversity more effectively? In this section, we review research findings and the best practices from different companies to create a list of suggestions for organizations.

Build a Culture of Respect for Diversity

In the most successful companies, diversity management is not the responsibility of the human resources department. Starting from top management and including the lowest levels in the hierarchy, each person must understand the importance of respecting others. If this respect is not part of an organization’s culture, no amount of diversity training or other programs are likely to be effective. In fact, in the most successful companies, diversity is viewed as everyone’s responsibility. Rogers Communications Inc. partners with Career Bridge to provide work to internationally educated professionals. Accenture Inc. has a global Persons with Disabilities Champions program, which is focused on workplace accommodations. Finally, British Columbia Hydro and Power Authority encourages managers to hire skilled newcomers, providing a career advancement plan (Jermyn, 2018).

L’Oréal – a leading cosmetics company, also has a commitment to gender equality, with 69% of its workforce made up of women. L’Oréal achieves this by having a detailed diversity-and-inclusion strategy that the company implements at locations around the world, resulting in positive changes in its communities and elevating women into leadership positions across the company.

Lenovo, a global PC provider, has built its company on the concept that “different is better,” championing and weaving diversity into the fabric of its business. Lenovo has scored 100% on the Corporate Equality Index, a benchmarking report on corporate policies and practices regarding LGBTQIA equality, in both 2017 and 2019. The report evaluates LGBTQIA-related policies and practices, such as non-discrimination, workplace protections, domestic partner benefits and transgender-inclusive healthcare benefits.

The lesson to take from Lenovo is that the inclusion of progressive and inclusive policies and benefits helps you attract talent and makes more employees feel supported at work.

Companies with a strong culture, where people have a sense of shared values, is rewarded with loyalty and team performance. This enables employees with vastly different demographics and backgrounds to feel a sense of belonging (Chatman et al., 1998; Fisher, 2004).

Make Managers Accountable for Diversity

People are more likely to pay attention to aspects of performance that are measured. In successful companies, diversity metrics are carefully tracked. For example, in PepsiCo, during the tenure of former CEO Steve Reinemund, half of all new hires had to be either women or minorities. Bonuses of managers partly depended on whether they had met their diversity-related goals (Yang, 2006).

Ajay Banga, former CEO of Mastercard for 12 years, who led the company through a strategic, technological and cultural transformation said: “My passion for diversity comes from the fact that I myself am diverse. There have been a hundred times when I have felt different from other people in the room or in the business. I have a turban and a full beard, and I run a global company—that’s not common.”

Mr. Banga in this excerpt from his talk at Stanford University has a simple solution for diversity. “We must surround ourselves with people who don’t look the same and have had different experiences. It is the best way to ensure we don’t fall victim to the same blind spots again and again and again,” he said.

During his tenure as CEO, Mr. Banga ensured through his business leaders that men and women at Mastercard , at the same hierarchical level, were paid the same. This was not the case before he joined the company.

When managers are evaluated and rewarded based on how effective they are in diversity management, they are more likely to show commitment to diversity that in turn affects the diversity climate in the rest of the organization.

Diversity Training Programs

Many companies provide employees and managers with training programs related to diversity. However, not all diversity programs are equally successful. If the program is not enforced and modeled by leadership, employees will lack the motivation to buy-in. If employees sense there is no commitment and accountability from senior leaders, it will impact the motivation and enthusiasm needed to implement a successful Diversity program.

A Diversity program cannot succeed in the absence of adequate representation of diverse groups of people. One key hindrance is the perception of diversity as anything other than meaning the inclusion of people of distinct ages, genders, ethnicities, social classes, income levels, and different cultural backgrounds.

You may expect that more successful programs are those that occur in companies where a culture of diversity exists. A study of over 700 companies found that programs with a higher perceived success rate were those that occurred in companies where top management believed in the importance of diversity, where there were explicit rewards for increasing diversity in the company, and where managers were required to attend the diversity training programs (Rynes & Rosen, 1995).

Review Recruitment Practices

Companies may want to increase diversity by targeting a pool that is more diverse. There are many minority professional groups such as The Aboriginal Women’s Professional Association (AWPA) which provides “Aboriginal women from all over Canada the opportunity to gather and meet other Aboriginal women and to learn from each other” (Charity Village, 2019). By building relationships with these occupational groups, organizations may attract a more diverse group of candidates to choose from. The auditing company Ernst & Young Global Ltd. increases diversity of job candidates by mentoring undergraduate students (Nussenbaum, 2003). Companies may also benefit from reviewing their employment advertising to ensure that diversity is important at all levels of the company (Avery, 2003).

Today’s job seekers have numerous tools available—from Glassdoor to LinkedIn—to evaluate a company before they ever apply for a job. Focusing on Diversity in the company’s branding efforts is key to a diversity recruiting strategy. A strong employer brand will help you attract qualified candidates who want to work for the company.

2.2 Cultural Diversity

Culture refers to values, beliefs, and customs that exist in a society. In the United States, the workforce is becoming increasingly multicultural, with close to 16% of all employees being born outside the country. In addition, the world of work is becoming increasingly international. The world is going through a transformation in which China, India, and Brazil are emerging as major players in world economics. Companies are realizing that doing international business provides access to raw materials, resources, and a wider customer base. For many companies, international business is where most of the profits lie, such as for Apple Inc. In the second quarter of fiscal year 2021, around 67 percent of Apple Inc’s revenue was generated outside of the United States.

International companies are also becoming major players with foreign investors. Originally a Swedish company, Spotify now has headquarters in multiple areas across the globe including New York City. While its CEO and founder holds a large percentage of the company, Chinese investor Tencent Holdings Limited LLC bought 10% of the company back in 2017 while Spotify bought 10% of Tencent’s holdings.

Americans are unlikely to see new, foreign brands on grocery store shelves anytime soon. Instead, they will be buying Entenmann’s mini-chocolate chip cookies owned by Mexican firm Grupo Bimbo instead.

As a result of these trends, understanding the role of national culture for organizational behaviour may provide you with a competitive advantage in your career. In fact, sometime in your career, you may find yourself working as an expatriate. An expatriate is temporarily assigned to a position in a foreign country. Such an experience may be invaluable for your career and challenge you to increase your understanding and appreciation of differences across cultures.

How do cultures differ from each other? If you have ever visited a country different from your own, you probably have stories to tell about what aspects of the culture were different and which were similar. Maybe you have noticed that in many parts of Canada people routinely greet strangers with a smile when they step into an elevator or see them on the street, but the same behaviour of saying hello and smiling at strangers would be considered odd in many parts of Europe. In India and other parts of Asia, traffic flows with rules of its own, with people disobeying red lights, stopping and loading passengers in highways, or honking continuously for no apparent reason. In fact, when it comes to culture, we are like fish in the sea: we may not realize how culture is shaping our behaviour until we leave our own and go someplace else. Cultural differences may shape how people dress, act, eat, form relationships, address each other, and many other aspects of daily life.

Thinking about hundreds of different ways in which cultures may differ is not very practical when you are trying to understand how culture affects work behaviours. For this reason, the work of Geert Hofstede, a Dutch social scientist, is an important contribution to the literature. Hofstede studied IBM employees in 66 countries and showed variations among national cultures across four important dimensions. Research also shows that cultural variation with respect to these four dimensions influence employee job behaviours, attitudes, well-being, motivation, leadership, negotiations, and many other aspects of organizational behaviour (Hofstede, 1980; Tsui, Nifadkar, & Ou, 2007).

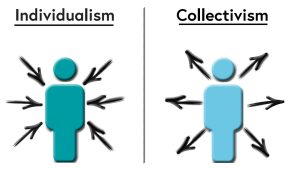

|

Individualism Cultures in which people define themselves as individuals and form looser ties with their groups. |

Collectivism Cultures where people have stronger bonds to their group and membership forms a person’s self-identity. |

|

|

|

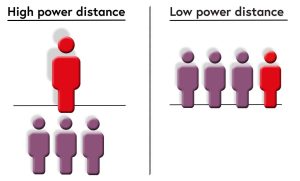

Low Power Distance A society that views an unequal distribution of power as relatively unacceptable. |

High Power Distance A society that views an unequal distribution of power as relatively acceptable. |

|

|

|

Low Uncertainty Avoidance Cultures in which people are comfortable in unpredictable situations and have high tolerance for ambiguity. |

High Uncertainty Avoidance Cultures in which people prefer predictable situations and have low tolerance for ambiguity. |

|

|

|

Masculinity Cultures in which people value achievement and competitiveness, as well as acquisition of money and other material objects. |

Femininity Cultures in which people value maintaining good relationships, caring for the weak, and quality of life. |

|

|

Figure 2.3 Hofstede’s culture framework is a useful tool to understand the systematic differences across cultures. Source: Adapted from information in Geert Hofstede cultural dimensions. Retrieved November 12, 2008, from http://www.geert-hofstede.com/hofstede_dimen-sions.php.

Individualism-Collectivism

Individualistic cultures are cultures in which people define themselves as an individual and form loose ties with their groups. These cultures value autonomy and independence of the person, self-reliance, and creativity. Countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia are examples of individualistic cultures. In contrast, collectivistic cultures are cultures where people have stronger bonds to their groups and group membership forms a person’s self-identity. Asian countries such as China and Japan, as well as countries in South America are higher in collectivism.

In collectivistic cultures, people define themselves as part of a group. In fact, this may be one way to detect people’s individualism-collectivism level. When individualists are asked a question such as “Who are you? Tell me about yourself,” they are more likely to talk about their likes and dislikes, personal goals, or accomplishments. When collectivists are asked the same question, they are more likely to define themselves in relation to others, such as “I am Chinese” or “I am the daughter of a doctor and a homemaker. I have two brothers.” In other words, in collectivistic cultures, self-identity is shaped to a stronger extent by group memberships (Triandis, McCusker, & Hui, 1990).

Other traits of collectivist cultures are:

- Greater emphasis is placed on common goals than on individual pursuits.

- The rights of families and communities come before those of the individual.

- Group loyalty is encouraged.

- Decisions are based on what is best for the group.

- Compromise is favored when a decision needs to be made to achieve greater levels of peace.

Collectivists are more attached to their groups and have more permanent attachments to these groups. Conversely, individualists attempt to change groups more often and have weaker bonds to them. It is important to recognize that to collectivists the entire human universe is not considered to be their in- group. In other words, collectivists draw sharper distinctions between the groups they belong to and those they do not belong to. They may be nice and friendly to their in-group members while acting much more competitively and aggressively toward out-group members. This tendency has important work implications. While individualists may evaluate the performance of their colleagues more accurately, collectivists are more likely to be generous when evaluating their in-group members.

Freeborders, a software company based in San Francisco, California, found that even though it was against company policy, Chinese employees were routinely sharing salary information with their coworkers. This situation led them to change their pay system by standardizing pay at job levels and then giving raises after more frequent appraisals (Frauenheim, 2005; Hui & Triandis, 1986; Javidan & Dastmalchian, 2003; Gomez, Shapiro, & Kirkman, 2000).

Collectivistic societies emphasize conformity to the group. The Japanese saying “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down” illustrates that being different from the group is undesirable. In these cultures, disobeying or disagreeing with one’s group is difficult and people may find it hard to say no to their colleagues or friends. Instead of saying no, which would be interpreted as rebellion or at least be considered rude, they may use indirect ways of disagreeing, such as saying “I have to think about this” or “this would be difficult.” Such indirect communication prevents the other party from losing face but may cause misunderstandings in international communications with cultures that have a more direct style. Collectivist cultures may have a greater preference for team-based rewards as opposed to individual- based rewards.

Power Distance

Power distance refers to the degree to which the society views an unequal distribution of power as acceptable. Simply put, some cultures are more egalitarian than others.

Countries with high Power Distance scores are generally those with stark hierarchies, where the less powerful are taught to “know their place” and respect authority. High PDI scores correlate with deferential relationships between students and teachers, children and parents, wives and husbands, employees and employers, subjects and rulers.

Countries with low Power Distance scores, lack the observance of differences in rank and status. People from these countries are less likely to drastically change their manner of speaking depending on the status of the person they are addressing.

For example, Thailand is a high-power distance culture and starting from childhood, people learn to recognize who is superior, equal, or inferior to them. When passing people who are more powerful, individuals are expected to bow, and the more powerful the person, the deeper the bow would be (Pornpitakpan, 2000). Managers in high power distance cultures are treated with a higher degree of respect, which may surprise those in lower power distance cultures. A Citibank manager in Saudi Arabia was surprised when employees stood up every time he passed by (Denison, Haaland, & Goelzer, 2004). Similarly, in Turkey and India, students in elementary and high schools greet their teacher by standing up every time the teacher walks into the classroom. In these cultures, referring to a manager or a teacher with their first name would be extremely rude. The behaviours in high power distance cultures may easily cause misunderstandings with those from low power distance societies. For example, a limp handshake in India or a job candidate from Chad (North African country) who looks at the floor throughout the interview are in fact forms of showing respect, but these behaviours may be interpreted as a lack of confidence or even disrespect in low power distance cultures.

One of the most important ways in which power distance is manifested in the workplace is that in high power distance cultures, employees are unlikely to question the power and authority of their manager, and conformity to the manager will be expected. Managers in these cultures may be more used to an authoritarian style with lower levels of participative leadership demonstrated. People will be more sub- missive to their superiors and may take orders without questioning the manager (Kirkman, Gibson, & Shapiro, 2001). In these cultures, people may feel uncomfortable when they are asked to participate in decision making. For example, peers are much less likely to be involved in hiring decisions in high power distance cultures. Instead, these cultures seem to prefer paternalistic leaders—leaders who are authoritarian but make decisions while showing a high level of concern toward employees as if they were family members (Javidan & Dastmalchian, 2003; Ryan et al., 1999).

Uncertainty Avoidance

Uncertainty avoidance refers to the degree to which people feel threatened by ambiguous, risky, or unstructured situations. Cultures high in uncertainty avoidance prefer predictable situations and have low tolerance for ambiguity. Employees in these cultures expect a clear set of instructions and clarity in expectations. Therefore, there will be a greater level of creating procedures to deal with problems and writing out expected behaviours in manuals.

Cultures high in uncertainty avoidance prefer to avoid risky situations and attempt to reduce uncertainty. For example, one study showed that when hiring new employees, companies in high uncertainty avoidance cultures are likely to use a larger number of tests, conduct a larger number of interviews, and use a fixed list of interview questions (Ryan et al., 1999). Employment contracts tend to be more popular in cultures higher in uncertainty avoidance compared to cultures low in uncertainty avoidance (Raghuram, London, & Larsen, 2001). The level of change-oriented leadership seems to be lower in cultures higher in uncertainty avoidance (Ergeneli, Gohar, & Temirbekova, 2007). Companies operating in high uncertainty avoidance cultures also tend to avoid risky endeavors such as entering foreign target markets unless the target market is very large (Rothaermel, Kotha, & Steensma, 2006).

Germany is an example of a high uncertainty avoidance culture where people prefer structure in their lives and rely on rules and procedures to manage situations. Similarly, Greece is a culture relatively high in uncertainty avoidance, and Greek employees working in hierarchical and rule-oriented companies report lower levels of stress (Joiner, 2001). In contrast, cultures such as Iran and Russia are lower in uncertainty avoidance, and companies in these regions do not have rule-oriented cultures. When they create rules, they also selectively enforce rules and make a number of exceptions to them. In fact, rules may be viewed as constraining. Uncertainty avoidance may influence the type of organizations employees are attracted to. Japan’s uncertainty avoidance is associated with valuing job security, while in uncertainty-avoidant Latin American cultures, many job candidates prefer the stability of bigger and well-known companies with established career paths.

Masculinity–Femininity

Masculine cultures value achievement, competitiveness, and acquisition of money and other material objects. Japan and Hungary are examples of masculine cultures. Masculine cultures are also characterized by a separation of gender roles. In these cultures, men are more likely to be assertive and competitive compared to women.

In contrast, feminine cultures are cultures that value maintaining good relationships, caring for the weak, and emphasizing quality of life. In these cultures, values are not separated by gender, and both women and men share the values of maintaining good relationships. Sweden and the Netherlands are examples of feminine cultures.

The level of masculinity inherent in the culture has implications for the behaviour of individuals as well as organizations. For example, in masculine cultures, the ratio of CEO pay to other management-level employees tends to be higher, indicating that these cultures are more likely to reward CEOs with higher levels of pay as opposed to other types of rewards (Tosi & Greckhamer, 2004). The femininity of a culture affects many work practices, such as the level of work/life balance. In cultures high in femininity such as Norway and Sweden, work arrangements such as telecommuting seem to be more popular compared to cultures higher in masculinity like Italy and the United Kingdom.

2.3 Managing Diversity for Success: The Case of IBM

When you are a company that operates in over 170 countries with a workforce of over 398,000 employees, understanding and managing diversity effectively is not optional—it is a key business priority. A company that employs individuals and sells products worldwide needs to understand the diverse groups of people that make up the world.

Starting from its early history in the United States, IBM Corporation (NYSE: IBM) has been a pioneer in valuing and appreciating its diverse workforce. In 1935, almost 30 years before the Equal Pay Act guaranteed pay equality between the sexes, then IBM president Thomas Watson promised women equal pay for equal work. In 1943, the company had its first female vice president. Again, 30 years before the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) granted women unpaid leave for the birth of a child, IBM offered the same benefit to female employees, extending it to one year in the 1960s and to three years in 1988. In fact, the company ranks in the top 100 on Working Mother magazine’s “100 Best Companies” list and has been on the list every year since its inception in 1986. It was awarded the honour of number 1 for multicultural working women by the same magazine in 2009.

IBM has always been a leader in diversity management. Yet, the way diversity was managed was primarily to ignore differences and provide equal employment opportunities. This changed when Louis Gerstner became CEO in 1993.

Gerstner was surprised at the low level of diversity in the senior ranks of the company. For all the effort being made to promote diversity, the company still had what he perceived a masculine culture.

In 1995, he created eight diversity task forces around demographic groups such as women and men, as well as Asians, African Americans, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) individuals, Hispanics, Native Americans, and employees with disabilities. These task forces consisted of senior-level, well-respected executives and higher-level managers, and members were charged with gaining an understanding of how to make each constituency feel more welcome and at home at IBM. Each task force conducted a series of meetings and surveyed thousands of employees to arrive at the key factors concerning each particular group. For example, the presence of a male-dominated culture, lack of networking opportunities, and work-life management challenges topped the list of concerns for women. Asian employees were most concerned about stereotyping, lack of networking, and limited employment development plans. African American employee concerns included retention, lack of networking, and limited training opportunities. Armed with a list of priorities, the company launched a number of key programs and initiatives to address these issues. As an example, employees looking for a mentor could use the company’s website to locate one willing to provide guidance and advice. What is probably most unique about this approach is that the company acted on each concern whether it was based on reality or perception. They realized that some women were concerned that they would have to give up leading a balanced life if they wanted to be promoted to higher management, whereas 70% of the women in higher levels actually had children, indicating that perceptual barriers can also act as a barrier to employee aspirations. IBM management chose to deal with this particular issue by communicating better with employees as well as through enhancing their networking program.

The company excels in its recruiting efforts to increase the diversity of its pool of candidates. One of the biggest hurdles facing diversity at IBM is the limited minority representation in fields such as computer sciences and engineering. For example, only 4% of students graduating with a degree in computer sciences are Hispanic. To tackle this issue, IBM partners with colleges to increase recruitment of Hispanics to these programs. In a program named EXITE (Exploring Interest in Technology and Engineering), they bring middle school female students together for a week-long program where they learn math and science in a fun atmosphere from IBM’s female engineers. To date, over 3,000 girls have gone through this program.

What was the result of all these programs? IBM tracks results through global surveys around the world and identifies which programs have been successful and which issues are no longer viewed as problems. These programs were instrumental in more than tripling the number of female executives worldwide as well as doubling the number of minority executives. The number of LBGT executives increased sevenfold, and executives with disabilities tripled. With growing emerging markets and women and minorities representing a $1.3 trillion market, IBM’s culture of respecting and appreciating diversity is likely to be a source of competitive advantage.

Based on information from Ferris, M. (2004, Fall). What everyone said couldn’t be done: Create a global women’s strategy for IBM. The Diversity Factor, 12(4), 37–42; IBM hosts second annual Hispanic education day. (2007, December–January). Hispanic Engineer, 21(2), 11; Lee, A. M. D. (2008, March). The power of many: Diversity’s competitive advantage. Incentive, 182(3), 16–21; Thomas, D. A. (2004, September). Diver- sity as strategy. Harvard Business Review, 82(9), 98–108.

2.4 Conclusion

In conclusion, in this chapter we reviewed the implications of demographic and cultural diversity for organizational behaviour. Management of diversity effectively promises a number of benefits for companies and may be a competitive advantage. Yet, challenges such as natural human tendencies to associate with those similar to us and using stereotypes in decision making often act as barriers to achieving this goal. By creating a work environment where people of all origins and traits feel welcome, organizations will make it possible for all employees to feel engaged with their work and remain productive members of the organization.

2.5 Exercises

Mini Case Scenario

Deriving benefits of Diversity & Inclusion needs to be managed

Hector Resources Inc. is a mining company operating in a remote area of Canada. The company had hired a significant number of Indigenous workers from the nearby communities to work in the mine. However, they were facing several challenges in managing the workforce due to cultural differences.

One of the primary challenges was the communication barrier. The Indigenous workers spoke their local language, which was different from the language spoken by the non-Indigenous supervisors. This led to misunderstandings, and sometimes the workers were not able to understand the instructions given to them. This resulted in a loss of productivity and increased safety risks.

Another challenge was the difference in work values and expectations. The Indigenous workers had different attitudes towards time management, work ethic, and hierarchy. For example, they placed a high value on family and community obligations and were more likely to prioritize them over work. This led to conflicts with the non-Indigenous supervisors, who expected the workers to prioritize work over other obligations.

Adam Maxwell, the CEO at Hector Resources Inc. had recently attended a seminar on the benefits of adopting Diversity and Inclusion practices by firms and was determined to see that his company gained from these. However, he realized that managing an Indigenous workforce requires a deep understanding of their culture, values, and traditions. Organizations must be willing to adapt their management practices to accommodate these differences and create a work environment that is inclusive and respectful of cultural diversity. By doing so, organizations can benefit from the unique perspectives and skills of Indigenous workers and create a more harmonious and productive workplace.

A concerted effort was required if the company wanted to avail of the benefits.

Adam Maxwell wants to hire you as an external consultant to propose measures to address the challenges such as barriers and differences identified above. If your proposal is seen to aid with the Diversity and Inclusion efforts, you would be hired to implement your proposal.

Propose specific measures that the company should undertake to tackle the identified challenges.